In a quiet fishing village along the banks of the Mae Klong River in Siam—modern-day Thailand—two boys were born under a sky of uncertainty in 1811. They shared not just a birth, but a body. A thick band of flesh at the chest united them, an umbilical knot of fate binding them not just to each other but to history. Their names were Chang and Eng, and in time, the world would know them as the original Siamese Twins—a term etched into medical vocabulary and cultural imagination for centuries.

They were not royalty, nor born into wealth or prestige. Their father was Chinese; their mother, half-Chinese and half-Malay. They were not expected to survive, let alone thrive. Yet what began as an anomaly of biology transformed into one of the most astonishing human stories of the 19th century. Their journey would span continents, spark international debate, and leave behind a legacy that was equal parts marvel and tragedy.

From Curiosity to Commodity

Discovered by a Scottish merchant named Robert Hunter during a chance encounter in 1824, the teenage twins were quickly swept into a world of Western spectacle. At the time, Europe and America were enchanted by “human oddities.” The colonial gaze turned people from distant lands into objects—fascinating, frightening, and profitable. Chang and Eng were no exception.

In 1829, they began touring the United States and the United Kingdom, displayed before crowds like living puzzles. They wore elegant jackets, rehearsed speeches, and walked in near-perfect unison. Though treated as exotic exhibits, they proved to be sharp, witty, and dignified, often controlling their own public narrative. But fame came at a cost. Though they earned money and admiration, they were also seen through a lens of otherness—neither fully human in the eyes of their audiences nor fully in control of their lives.

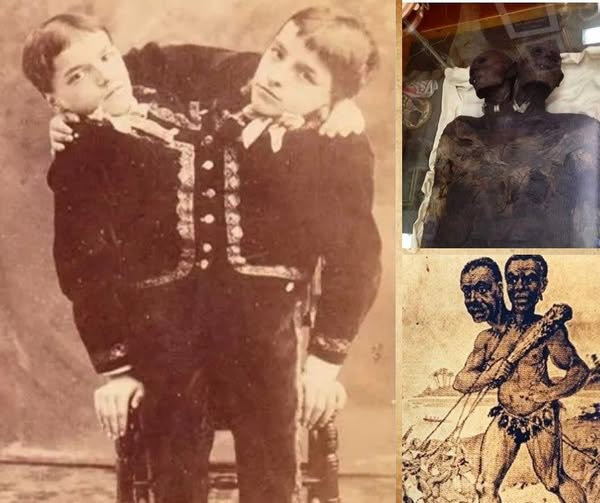

Their image, as shown in the left section of the image above, captures this duality. Dressed in coordinated suits, standing with poise, they appear almost like aristocrats. Yet behind the polished performance lay an exhausting reality: the loss of privacy, autonomy, and the ability to choose solitude.

From Spectacle to Settlement

Eventually, the twins sought independence. After a decade of exhibitions, they severed ties with their managers and became their own agents. By 1839, they had settled in Wilkes County, North Carolina. There, they did something even more astonishing—they became American citizens, bought land, and, in a deeply ironic twist, became slave owners.

In 1843, Chang and Eng married two sisters, Adelaide and Sarah Yates, and over the years fathered 21 children between them. They even built two separate homes, taking turns living three days in each household to maintain peace between the families. Their union with the Yates sisters was controversial, and their personal lives became the subject of whispers, tabloids, and scientific inquiry alike.

How did love work between the conjoined? Did affection divide evenly, or did one feel more, give more, want more? What happens to desire when the body must share its every breath with another?

These were not just scientific questions, but deeply human ones.

A Life Lived in Twos

Their physical union was both prison and partnership. Joined at the sternum by a five-inch bridge of cartilage and connected internally by a shared liver, the twins learned to accommodate each other’s rhythms. But with age, the harmony waned. Chang began drinking heavily, and his health declined rapidly. In 1874, after a stroke left Chang partially paralyzed, Eng bore the full weight of their shared existence. The pH๏τograph in the top-right corner of the image above shows their mummified remains—frozen in death just as they were in life, side by side.

On the morning of January 17, 1874, Eng awoke to find Chang cold and lifeless beside him. According to reports, Eng cried out in anguish, “Then I am going!”—and within three hours, he too was ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

Was it grief? A medical reaction? Or simply the collapse of a body that could not function without its counterpart?

The question still lingers in the margins of science and sentiment.

A Legacy Etched in Flesh

Their autopsy, a grim scientific curiosity, revealed a fused liver—impossible to separate without fatal consequences. It confirmed what many suspected: their lives were bound not just by skin, but by the very core of their bodies. Their death sparked renewed fascination, and for decades their preserved body was displayed in the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, where thousands stared at the remains that once loved, laughed, fought, and lived.

The bottom-right image—a crude etching—shows them laboring in chains, possibly a metaphor or satirical take on their condition. Were they slaves to each other? Or masters of a shared destiny?

Their story has inspired books, plays, films, and ethical debates about idenтιтy, autonomy, and what it means to be human. But perhaps their greatest legacy lies not in medical texts or museum displays, but in how they shattered the boundaries of singularity.

Human After All

Chang and Eng were not monsters or marvels. They were men—brothers, husbands, fathers, and immigrants—who wrestled with the hand fate had dealt them. They navigated a world eager to reduce them to a curiosity, and in doing so, they carved out a space for dignity within spectacle, agency within confinement.

Their lives force us to reflect on our own notions of individuality and interdependence. In a time when personal freedom is held sacred, their existence reminds us of the quiet, daily negotiations of togetherness—how we compromise, how we adapt, and how we survive by leaning on each other.

They lived one of the most physically intertwined lives in recorded history. And yet, they never stopped striving to be seen as two.

Would we have done the same? Would we have had the strength not just to endure, but to love, create, and claim a place in the world—not in spite of our limitations, but because of them?

And if your every step, every breath, every moment was shared—would you still feel like yourself?

Or would you discover that the line between me and we was never as clear as you thought?