In the heart of the Egyptian desert, beneath layers of golden sand and collapsed stone, a team of archaeologists brushed away the dust of centuries. Their tools were delicate, their hands steady, their silence reverent. They had broken through to a sealed chamber—a resting place undisturbed for over three millennia. The air was thick with mystery, the scent of ancient resin and timeworn wood curling through the darkness.

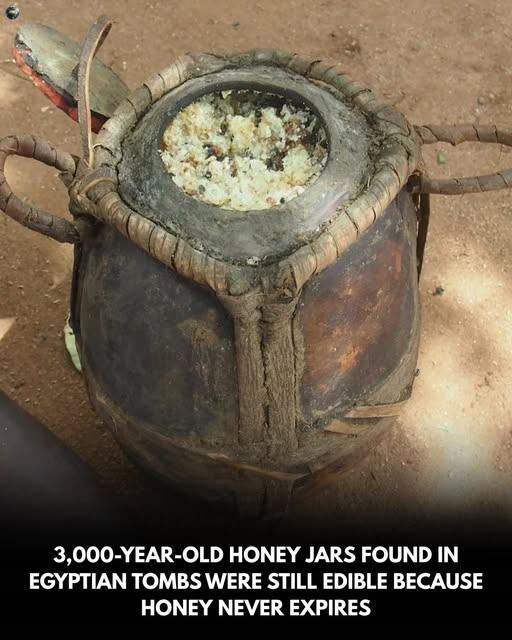

Among the gold funerary masks, alabaster jars, and intricately painted canopic chests, one object stood apart—not in grandeur, but in its quiet defiance of time. It was a humble clay jar, sealed with wax and rope, its surface etched with hieroglyphs worn faint by the ages. The team expected grain, dried meat, perhaps some sacred ointment. What they found instead was honey—still viscous, still golden, still sweet.

3,000 years had pᴀssed since this honey was placed lovingly beside the body of a nobleman or pharaoh. It was meant to nourish the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ in the afterlife, to be a balm for the journey through Duat, the underworld. And yet, as the lid was removed, there it was: the same honey that once flowed through the hands of ancient apiarists by the banks of the Nile. Not crystallized. Not fermented. Not spoiled. Simply… eternal.

Honey: Food of the Gods, Preserver of Time

In ancient Egypt, honey was more than a luxury—it was a sacred substance. Harvested from carefully tended hives and guarded like treasure, honey was a symbol of purity, healing, and divine power. Bees themselves were seen as messengers of the gods, born from the tears of Ra. Priests offered honey at temple altars; embalmers used it to anoint bodies. Pharaohs demanded it in their rations. Even the poorest citizens, if lucky, might taste it once in their lives.

The Egyptians believed honey bridged worlds: the mortal and the divine, the present and the eternal. That belief found its echo in tombs across the land. Archaeologists have uncovered jars of honey dating as far back as 1300 BCE, perfectly preserved beside bread, wine, and dried fruits. These offerings weren’t just symbolic—they were real provisions for the soul’s long journey.

And science would later explain what the ancients knew intuitively: honey never spoils. Its low water content and high acidity prevent bacteria and microorganisms from growing. Add in the natural presence of hydrogen peroxide, and honey becomes one of the most stable organic substances known to humankind. It is alchemy in a jar—preserved not by spell or charm, but by nature’s own chemistry.

A Taste of the Past

Dr. Leila Nᴀssar, one of the archaeologists present during the 2003 excavation at Saqqara, described the moment she tasted the ancient honey. “It was a whisper on the tongue,” she said in an interview. “Like the desert itself had remembered something sweet, something forgotten.”

She dipped a sterile tool into the jar and brushed a drop onto her tongue. The flavor was rich, floral, earthy—nothing like the industrial sweetness of modern syrups. This was honey gathered from lotus blossoms and papyrus reeds, from acacia trees and wild desert herbs. It was a taste that hadn’t existed in centuries, reborn in an instant.

To eat that honey was to time-travel—not in theory, but in sensation. One could almost hear the hum of bees in an ancient grove, see the reed baskets dripping golden threads into clay pots, feel the presence of hands that once sealed it shut, believing it would nourish a soul forever.

What Endures and What Fades

There is something profoundly human about preserving food for the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. In a world that constantly slips through our fingers, we long to anchor ourselves in permanence. We embalm, we entomb, we write names in stone. And yet, over time, empires collapse, languages vanish, even the greatest monuments crumble.

But honey remains.

It is one of the rare substances that defies rot, that resists the slow erasure of time. It carries not just flavor, but memory. A single spoonful can outlast civilizations.

This is why the discovery of edible honey in an Egyptian tomb is more than a historical curiosity—it is a quiet miracle. In an age of planned obsolescence and constant reinvention, this humble jar reminds us that some things endure not through power, but through balance and grace.

A Message in a Jar

The ancients left us pyramids and papyri, obelisks and ossuaries. But perhaps their most poignant message was sealed inside a jar of honey: a whisper that says, “We were here. We loved. We prepared. We believed in forever.”

And that message still speaks—sticky, golden, sweet across the centuries.

So next time you stir honey into your tea, or spread it across warm bread, pause a moment. Think of the hands that first discovered its sweetness, the bees that danced in desert winds, the tombs dark and quiet where that same substance glowed like amber in the afterlife. Think of a civilization that knew, long before science confirmed it, that honey was a kind of eternity.

And ask yourself: in a world where so much fades, what sweetness might we leave behind?