In the arid valleys of Peru, where the wind whispers ancient names and the earth conceals more than it reveals, a peculiar burial was unearthed. It was not just a skeleton, but a skull—elongated, narrow, almost alien in its elegance. This was no accident of time or nature. It had been shaped. Sculpted. A head stretched beyond the limits of the familiar human form. And it was not alone.

For centuries, these so-called “elongated skulls” have puzzled archaeologists, ignited conspiracy theories, and inspired artists to reimagine the boundaries of what it means to be human. Found in places as distant as Paracas (Peru), the Nile Valley, Siberia, and the South Pacific, these skulls—some natural, some deformed through a practice known as cranial binding—have been exhumed from tombs like time-traveling messengers. What were these people trying to tell us, and who were they?

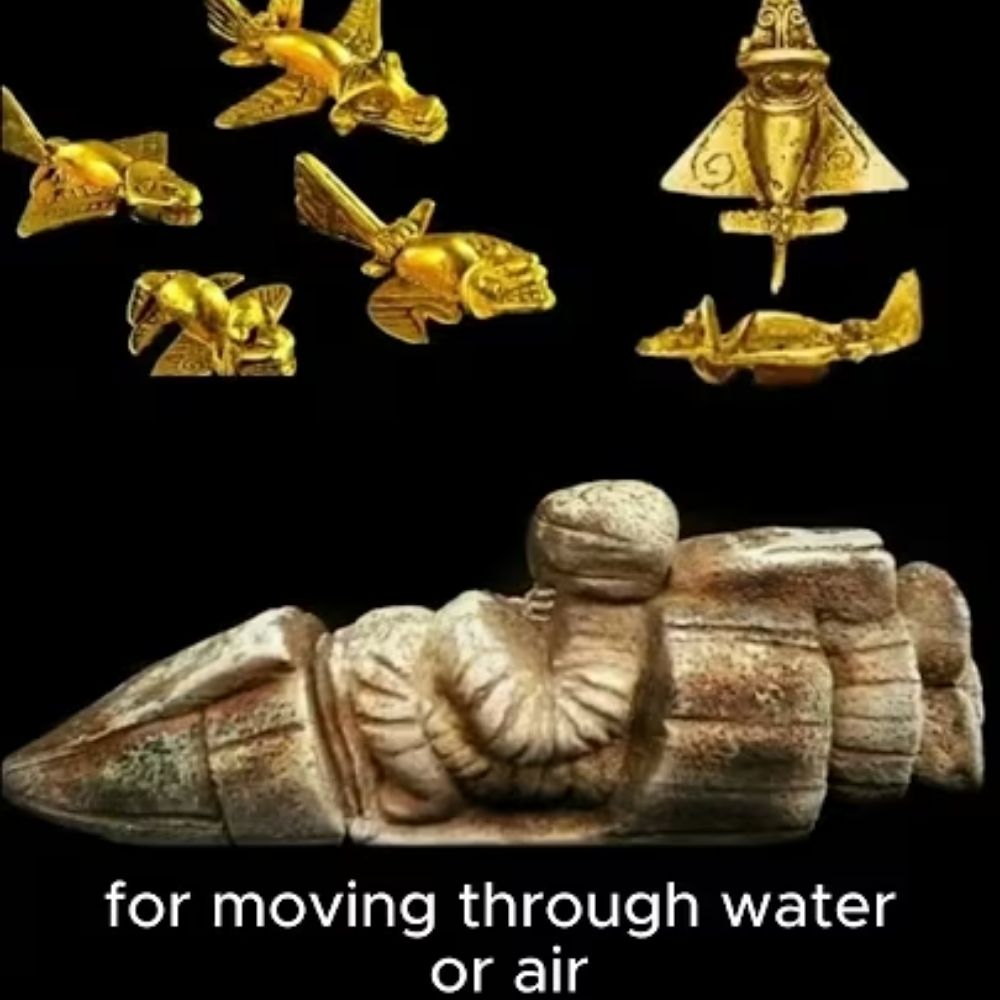

The image you see is a collage of relics and reconstructions—a mosaic of mystery. At the top and bottom, real skulls from museums and excavation sites. Their forms, though human, stretch upward like the aspirations of a forgotten culture. The central portion is something different: a series of anatomical sketches, a speculative reimagining of what these individuals might have looked like in life. The result is hauntingly beautiful. Elegant beings, regal in posture and intellect, their towering crania hinting at something we’ve lost.

The Art of Becoming Other

Cranial deformation is not an anomaly; it is a cultural phenomenon. Across the globe, from the ancient Maya to the Mangbetu of Congo, from the Huns to the Sarmatians, deliberate head shaping was practiced as a rite of pᴀssage, a mark of nobility, or a gesture toward the divine. In some cultures, the head was bound with cloth or boards during infancy, molding the soft skull over time into a more desirable form.

But why? Why endure such a transformation?

Perhaps it was a way to stand apart—to transcend the mundane and approach the celestial. A child with a reshaped skull grew up not just looking different, but being different. Revered. Elevated. In the context of social hierarchy, to possess an elongated head was to carry the mark of the elite, the chosen, the intermediary between humans and gods.

In the Paracas Peninsula of southern Peru, tombs dating back more than 2,000 years revealed a culture obsessed with this transformation. Their skulls were not just elongated—they were anatomically altered in ways that confound even modern forensic scientists. Some experts argue that certain Paracas skulls contain cranial volume far exceeding that of normal humans, with sutures and bone structures unfamiliar to classical anthropology. Could it be genetic? A lost lineage? Or are we misreading signs in the dust?

When Flesh Met Imagination

The central drawings are not from an ancient codex, though they feel like they should be. They are the artist’s attempt to bridge bone and soul, to breathe life into the static quiet of a museum. Muscles stretch taut over cheekbones. Eyes sink deep beneath overhanging brows. The cranial dome is not monstrous but dignified, as if evolution had chosen this path for its own reasons.

These reconstructions raise questions as much emotional as they are academic. Were these people feared or adored? Did they view the stars differently, with minds shaped—literally—for higher thought? Was this body modification merely ornamental, or did it accompany changes in how they saw the world, in how they loved, fought, and worshipped?

There’s something both futuristic and primordial in these faces. They look at us across time with cool intelligence, perhaps pitying our need to normalize all that deviates from the expected. In the long vaults of their skulls lies the ghost of imagination—the sense that once, humanity was not content with being merely human.

In the Museum of Secrets

The bottom row of the image shows skulls in glᴀss cases, quiet and still, with printed cards detailing their origin in dry, academic language. But these are not dry. They pulse with history. Behind each tag is a life, a mother who wrapped the infant’s head with cloth, a priest who proclaimed this new form sacred, a community that watched the child grow into a being they saw as somehow more.

Here lie no monsters, no aliens, no hoaxes. Only people—people who chose to sculpt themselves into symbols. That act alone deserves respect.

And yet, in a modern world quick to explain and quicker to dismiss, these skulls sit like riddles. Misunderstood. Misfiled. Sometimes, they are even co-opted by fringe theorists who would rather imagine extraterrestrial ancestors than reckon with the richness and strangeness of our own past.

But the truth, like the skull, is elongated. It doesn’t fit easily in the box we’ve made for it. We must let it stretch, breathe, take on shapes we don’t yet understand.

What Does the Head Remember?

If bones could speak, what would they say about the minds they housed? Would they whisper old songs, or chant the names of vanished gods? The ancient peoples who shaped their heads were making a statement not just about beauty or status, but about consciousness. About idenтιтy. Perhaps about the afterlife.

To change the skull is to alter the seat of thought, memory, and self. It is a kind of metaphysical rebellion—a declaration that our bodies are not fixed, but fluid, that we can remake ourselves in the image of our ideals.

This practice raises timeless questions: How far would you go to become something more? To touch the divine? What price would you pay to be set apart?

These are not the questions of ancient tribes alone. We ask them every time we look in the mirror and wonder who we might become.

Between Bones and Stars

The elongated skulls remind us that humanity has always been reaching—upward, inward, outward. In the shadows of temples and the corners of museums, they persist as emblems of that reach. Not artifacts of alien visitation, but proof of something even more remarkable: the human imagination made flesh.

Look again at those faces in the sketches. They are not so far from us. Their eyes hold curiosity, sadness, strength. Their brows furrow with thoughts we’ll never know. But they knew something. They believed in something. And they left behind these monuments to the strange, sacred art of becoming more.

Perhaps we are not meant to fully understand. Perhaps mystery is part of their message. And perhaps, in a world so eager to explain, these skulls offer a different wisdom:

That some truths are shaped not to fit, but to inspire.