In a secluded corner of the Altai Mountains, where the tundra meets the sky and ancient winds whisper through the frostbitten trees, a frozen tomb yielded an unexpected treasure. Beneath the soil, preserved in eternal ice, lay the Pazyryk Carpet—a woven echo of a forgotten world.

Discovered in 1949 by Russian archaeologist Sergei Rudenko, the carpet was found in the burial mound of a Scythian chieftain, one of many noble kurgans dotting the windswept landscape of Pazyryk. This burial site, thousands of years old, had remained sealed beneath layers of permafrost, an icy vault that protected not only the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ but also the fragile trappings of their lives.

When the frost receded, it revealed not just a carpet, but a window into the soul of an ancient civilization.

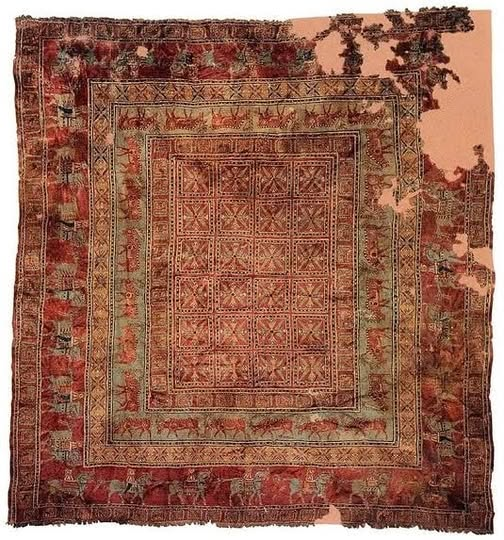

Measuring just under 2 meters on each side, the Pazyryk Carpet is astonishing in its complexity. Over 1.3 million individual knots form an intricate pattern of borders, symbols, and stories. Its perimeter bursts with galloping horsemen, each depicted in rich detail—broad-chested steeds, braided manes, and riders in tall headdresses carrying spears. Inside, a frieze of grazing deer interlaces with rows of geometric flowers, leading inward toward a central grid of stylized rosettes.

The palette, although subdued by time, retains its vitality. Deep reds drawn from madder root, blue from indigo, yellow from saffron—each shade chosen not merely for beauty, but for its meaning. Red, the color of vitality and protection. Blue, the realm of gods and skies. Yellow, the flame of divinity. Every knot, every hue, was intentional—a message woven in wool.

But whose hands wove it?

This remains a subject of scholarly debate. Some attribute the carpet to Persian artisans, citing its stylistic similarities to Achaemenid stone reliefs and courtly motifs. Others suggest an Armenian origin based on technical parallels. Still others point to the Scythians themselves—a nomadic warrior people, often dismissed as primitive, yet evidently capable of great artistic refinement. The carpet, then, becomes more than an artifact. It becomes a battleground of idenтιтies, a testament to the rich cultural entanglements of the ancient world.

It is no coincidence that the carpet was found in a tomb. In many ancient cultures, burial was not the end, but a pᴀssage—a voyage into the next life. The Scythian prince entombed in Pazyryk was sent into the afterlife with his finest possessions: horses, weapons, jewelry, a chariot… and this carpet. Not just a mat to lie upon, but a shield of meaning, a woven prayer to accompany the soul.

Remarkably, the carpet was not laid flat in the burial chamber. It had been folded, carefully arranged beneath the wooden platform on which the body rested. The intention is unclear. Was it to elevate the prince in death, or to shelter him? Was the act ritualistic, symbolic, or simply practical? Whatever the reason, it ensured the carpet’s survival.

The permafrost preserved it perfectly.

Unlike other ancient textiles, which have decayed into ghostly fragments, the Pazyryk Carpet remained whole. Its preservation is a miracle of coincidence—environmental, architectural, and ceremonial. The wooden tomb was sealed тιԍнтly; the ice crept in quickly. Oxygen was minimal. Insects could not thrive. The wool, dyed and knotted with meticulous care, endured not just centuries but millennia.

In the 21st century, it resides in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Behind glᴀss, under soft light, it draws visitors from across the globe. Historians marvel at its technique. Artists study its geometry. Anthropologists trace its motifs across cultures. But ordinary onlookers—those with no academic agenda—simply stare. Moved. Silenced. Awed.

There is something transcendent about it. A piece of fabric that has outlived empires. A thread of humanity that bridges past and present. While the names of its creators are lost, their legacy lives on—not in marble, not in metal, but in wool dyed with crushed flowers and tied by patient hands.

Consider the life of the artisan: perhaps a woman, seated cross-legged by firelight, repeating the same knot over and over, her fingers moving from memory. Perhaps she knew the prince. Perhaps she sang as she worked. Perhaps she wept when he died. Perhaps she never imagined that her work would be seen again—not by her children, not by her grandchildren, but by us, centuries later.

What other stories lie beneath the surface?

One theory posits that the carpet was a diplomatic gift—an object of prestige exchanged between kingdoms. Another suggests it was looted during a raid and repurposed in death. Yet another claims it was made explicitly for burial, never meant to be walked upon. Its pristine condition at the time of burial lends credence to this idea.

In each scenario, the carpet is more than decoration. It is communication. Of status. Of artistry. Of spiritual conviction.

And in a world obsessed with permanence, it offers a lesson in ephemerality. Fabric, after all, is not meant to last. It frays. It fades. It burns. Yet this one endured. It defied its nature. It became legend.

To see the Pazyryk Carpet is to touch the pulse of antiquity.

It reminds us that beauty was always part of being human—that the urge to create, to decorate, to leave a mark, is older than we imagine. It teaches us that art does not require permanence to be profound. That sometimes, the softest things endure the longest. That memory, like wool, can be knotted, dyed, and pᴀssed through time.

And when we stand before it, we do not just see a carpet.

We see a story—told without words, preserved without intent, and read across centuries by the heart.