In the scorched sands of Upper Egypt, within the sprawling ruins of Karnak Temple, stands a monument not only to the gods, but to defiance—an obelisk that whispers the legacy of a woman who ruled as king.

The Obelisk of Hatshepsut, hewn from a single shaft of rose-colored granite and hoisted skyward some 3,500 years ago, remains one of the most majestic testaments to ancient Egyptian power and artistry. It was raised during the reign of Hatshepsut, the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, who defied expectations, tradition, and patriarchy to carve her name into the annals of history—and into this very pillar of stone.

To understand this obelisk is to understand the will of a woman who claimed the тιтle of Pharaoh in a man’s world. Born the daughter of Thutmose I, Hatshepsut initially served as regent for her stepson, Thutmose III, but gradually ᴀssumed full kingship. She wore the false beard of kings, took male тιтles, and commissioned monuments equal in scale to any of her male predecessors. The obelisk at Karnak was among the boldest of these commissions.

Its journey began hundreds of kilometers south, in the stone quarries of Aswan. There, stonemasons, using copper chisels and dolerite pounders, shaped the obelisk from a single block of granite. Transported down the Nile on specially constructed barges, it was raised into position through a combination of ramps, ropes, and ritual—a feat of both engineering and spiritual precision. It was aligned carefully with the temple axis, so that the rays of the sun—embodied by Amun-Ra, the god to whom Hatshepsut devoted her rule—would strike it with unfiltered radiance.

In the hieroglyphs chiseled into its faces, Hatshepsut refers to herself not only as king, but as the beloved of Amun. Her inscriptions emphasize piety, legitimacy, and a divine mission. And yet, tucked between these lines of prayer is a pulse of bold ᴀssertion: Look upon my work, and know that I have outshone those who came before me.

But monuments are rarely left in peace. In later years, Thutmose III—once a child under her care, later a powerful ruler in his own right—tried to erase her memory. In many places across Egypt, her cartouches were chiseled out, her images defaced. Yet the obelisk remained. Perhaps it stood too tall, too symbolic, too sacred to destroy outright. Instead, it was entombed in a protective sheath of stone, hidden from view—buried in the hope of forgetting.

It would not be forgotten.

Centuries pᴀssed. Empires rose and crumbled. Thebes gave way to Luxor. The Nile shifted its course. And still, the obelisk remained. By the time Napoleon’s scholars arrived in Egypt, only fragments of its twin remained. But this monolith—now weathered but proud—continued to greet each sunrise as if it were still 1470 BCE.

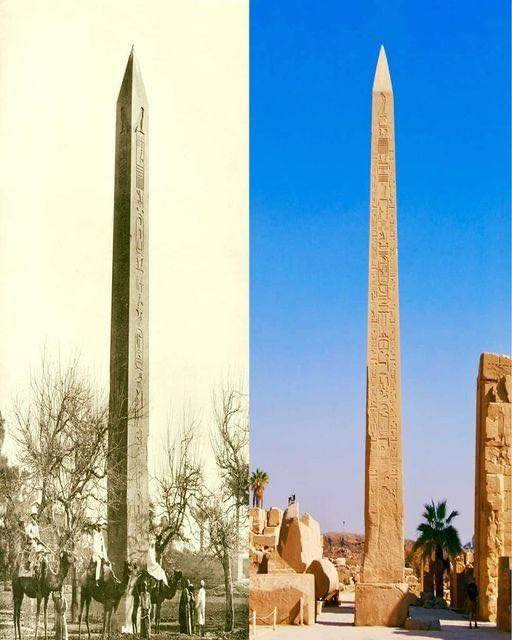

In the sepia-toned pH๏τograph on the left, taken in the late 19th or early 20th century, the obelisk looms like a ghost among bare trees and curious travelers on camels. Its shadow stretches across time, a silent reminder of how little the world understands the ones it tries to erase. And beside it, the modern color image reveals its restored context—bathed in golden light, surrounded by the sandstone ruins of Karnak, its hieroglyphs sharply etched against a cloudless Egyptian sky.

This obelisk is not just an object of archaeological interest. It is a message.

It speaks of gender and power. It speaks of ambition and piety. It tells of a civilization that believed in divine order and immortal memory. And it tells us something more elusive still: that the stories we try to hide often become the ones that endure longest.

Today, tourists from across the globe walk beneath it. Some glance upward with fleeting awe. Others linger, reading the inscriptions, wondering at the mind that commissioned such a work. And some—those who understand the quiet fury of being dismissed by history—see in it a reflection of their own resilience.

It is hard not to be moved.

This is not merely a monument of stone. It is a monument of will.

In the cool silence of dawn, as the first light brushes the obelisk’s tip, one might imagine Hatshepsut standing beneath it, arms raised not in supplication, but in declaration: I have done this. I have endured. Let the gods and the world bear witness.

And the stone does.

Still. Unshaken. Eternal.

<ʙuттon class="text-token-text-secondary hover:bg-token-bg-secondary rounded-lg" aria-label="Chia sẻ" aria-selected="false" data-state="closed">