Wes Anderson is one of our foremost film stylists working today. It’s the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about his work, and it’s the one thing everyone can agree on, even his critics. The look of his movies has evolved over the years, but anything of his is identifiably his.

What gets debated is how much that counts for. I don’t mean discussions of taste – there will always be those who enjoy being immersed in his aesthetic choices and those who don’t. But every film he makes reignites the same back-and-forth over style vs. substance, and whether the former is all he’s good for. Those who dismiss him often reduce him to his style, describe his latest movie as ‘the most Wes Anderson has ever Wes Andersoned’ and call it a day.

You might say I’m team substance, but I actually think the premise of this debate gets him totally wrong. Wes Anderson’s style isn’t at odds with substance, it is his substance. Anyone who thinks they need to unwrap his confections to get to the emotional core within is looking in the wrong place. And the proof is spread across his entire filmography: the contained stories of his early movies; his mid-career turn toward the meta in The Grand Budapest H๏τel; and his latest film, The Phoenician Scheme, which I think breaks fascinating new ground.

Wes Anderson’s Conspiratorial Style, Explained

Rethink The Traditional Relationship Between Style & Story

I think it’s common for people to think of a movie’s style as imposed, especially in movies as meticulously composed as Anderson’s. Directors are often portrayed as these forceful, exacting figures who use their films to shape the world in their image, and so aesthetic choices often end up read purely as expressions of their will. Things like character and story are just there in front of the camera, and style is applied on top; do too much, and you’ll smother them.

I don’t think this is correct in general – it relies on the old-fashioned idea that there’s a universal, perspectiveless truth you could capture on camera if you’d just stop injecting your ideas – but in this case, it’s wrong in a specific way. In Anderson’s filmography, the relationship between style and story is practically symbiotic. It’s not something he does to his characters, but for them. I call it conspiratorial style.

In each of these cases, Anderson styles them in their desired image – an image pretty clearly at odds with how most characters treat them.

A typical Wes Anderson protagonist tends to be someone at odds with the reality of their life. For whatever reason, the world doesn’t see them the way they see themselves. But the filmmaker, rather than work against them, takes their side. He shows them to us the way they’d want to be seen.

This traces all the way back to Bottle Rocket, his feature directorial debut, both in the sudden romance between Anthony and Inez and, especially, the ill-fated heist orchestrated by Owen Wilson’s eccentric Dignan. (If that sequence most previews the signature style that would follow, I think it’s because Anderson became more interested in the Dignans of the world than the Anthonys.) But I consider it a defining feature of all his work.

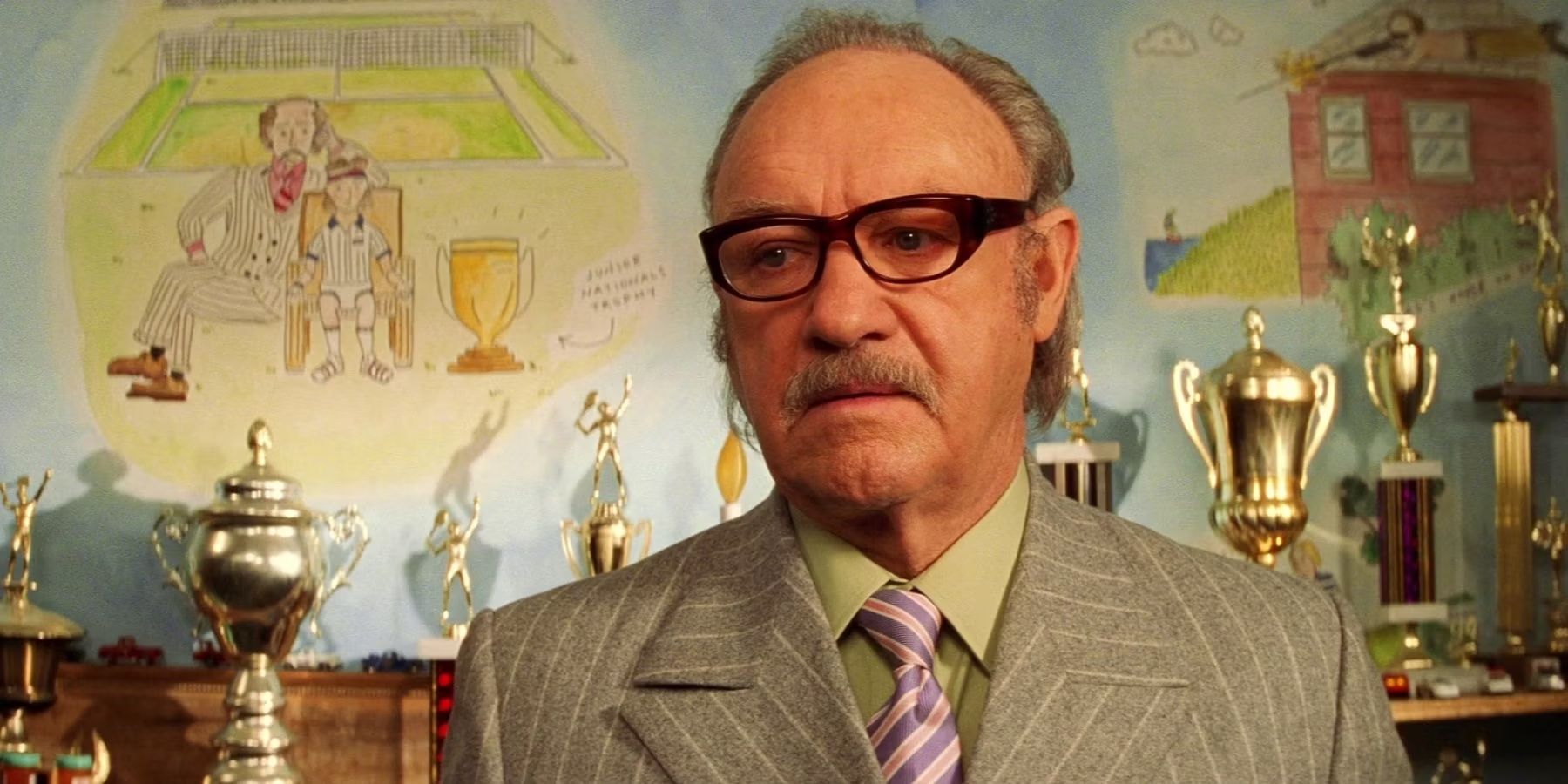

Rushmore‘s Max Fischer is an outcast at his preppy academy who fashions himself its most pre-eminent citizen. The Fantastic Mr. Fox‘s тιтular fox is a self-styled master thief going through a midlife crisis. Moonrise Kingdom‘s Sam and Suzy are lonely, misunderstood kids who find in each other the wild adventure and storybook romance they respectively sought. In each of these cases, Anderson styles them in their desired image – an image pretty clearly at odds with how most characters treat them.

Wes Anderson’s Movies Are Full Of Emotion

And His Style Helps Us Understand It

That element, in particular, is where the substance comes in. In none of his films is the veil so thick that it can’t be seen through, and as a result, these stories become about the feelings Anderson is helping the characters hide. Disappointment, grief, loneliness, aimlessness, anger, self-loathing. If you watch the movies understanding this from the get-go, as I have, they appear filled to the brim with emotion.

I believe The Royal Tenenbaums remains for many Anderson’s most emotionally accessible movie…

Most often, though, there are moments where the cup overflows. It’s not so much that the truth peeks through the shroud of style, but that the character being shrouded chooses to acknowledge it. They can be as small as a single, pregnant line of dialogue or an actor’s expression in close-up, and Anderson doesn’t dwell on them, letting the story continue ahead at the same pace. But see them for what they are, and they can really hit hard.

I believe The Royal Tenenbaums remains for many Anderson’s most emotionally accessible movie because the style’s dissonance with reality is apparent from the start. The Tenenbaums cling to an image rooted in the past – whatever inner turmoil was effectively concealed within these ‘child prodigy’ personas isn’t very well hidden by them now. Their pain is visible, bubbling right underneath the surface. So, when Chas finally says “I’ve had a rough year, Dad,” it’s as if all that feeling is concentrated into one, poignant spot.

But Moonrise Kingdom, my personal favorite, is a critical text here, too. Suzy and Sam are the heroes, and their young love is painted with an epic brush. But the adults of this story, shown how the two kids see them, are mostly left outside Anderson’s stylistic halo. Except for Sam’s Scout Master, who he actually respects, they are frustrated, disheveled, and sad. These are the people and feelings that populate every Wes Anderson movie, even if it doesn’t always look like it.

With The Grand Budapest H๏τel, Wes Anderson Went Meta

And His Stories Have Become About His Storytelling

The Grand Budapest H๏τel, one of Anderson’s most acclaimed movies to date, was a turning point in his approach to style as substance. His films had often featured voiceover narrators or storybook framing devices up to that point, but this one sports a nesting doll structure: a woman opens a book written by an author recalling his conversation with a H๏τel owner, who told him about his past and the H๏τel’s glory days. When you start a movie by diving through several layers of narration, you can’t help but focus on them.

He has since continued to interrogate this idea, and not just how it functions in his own work.

In this way, Anderson puts his own storytelling instincts under a microscope. It becomes undeniable that the way a story is told reflects the teller; just as Zero’s perspective is all over this tale of Gustav H., so too is Anderson’s perspective all over his movies. But, more than that, style is reflective of the relationship between the teller and the story. The past where most of the film takes place is rendered as beautiful as one of Mendl’s pastries because, for Zero, this narration is an act of love. The movie is about the emotional substance of style.

He has since continued to interrogate this idea, and not just how it functions in his own work. The French Dispatch (full тιтle: The French Dispatch of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun) is too quickly read as being about The New Yorker, which, in the abstract, it is. But, at the literal level, it’s worth noting that Anderson has taken an offshoot of a Kansas newspaper based in a small French village and treated it like it’s The New Yorker. Insтιтutions, too, can wish to be perceived differently than they are.

But what makes The French Dispatch one of my favorite of Anderson’s films is the way it explores what good writers do for their subjects. The style of each section in this anthology is distinct, reflective of both the character responsible for the story and how they feel about what they’re covering. He lets us see their mᴀssaging of the truth and revel in it – it’s through them that an unstable prisoner becomes an eccentric genius; a petulant boy an inspiring revolutionary; and a police chef an incisive artist.

Asteroid City has some of the same layering. Though trying to determine what’s literally happening will break your brain (and isn’t really the point), Anderson pulls off the wonderfully meta magic trick of depicting a performance of a play with all the vividness of a film adaptation, as if the cast’s shared imagination brings it to life. But the movie also does for actors what The French Dispatch does for writers. Performances, too, have style, and actors honor their characters in much the same way a filmmaker does.

In The Phoenician Scheme, Wes Anderson Tries Something A Little Different

And It Hints At His Next Career Chapter

Unsurprisingly, The Phoenician Scheme‘s Cannes premiere inspired the usual flock of reactions calling it just another Wes Anderson movie. But if you’re anything like me, this one will feel quite different. It’s darkly funny, but it’s also missing a certain lightness of tone that usually accompanies his creative flourishes. Even if the emotions of his stories are heavy, after he conspires with his protagonists to repackage them, they often don’t feel that way.

This latest feature is perhaps Anderson’s thorniest, and it took me a while to put my finger on why. But I’ve realized it’s because, this time, he’s not conspiring with his characters. He’s conspiring against them.

Sort of.

Spoilers for The Phoenician Scheme below!Benicio del Toro’s Zsa-Zsa Korda is not a typical Anderson hero, on the outside. He’s an enormously wealthy, callous тιтan of industry. He displays few qualms about resorting to slave labor to get his major infrastructure project finished, and spends much of the movie bewildered whenever someone doesn’t just follow his orders without question. His euology, heard at the beginning of the film when it’s erroneously ᴀssumed he died in his latest plane crash, is not kind.

But the man we hear about is never really the man we see. In a twist on what we’ve seen in Anderson’s films so far, this persona is just a style Korda’s wrapped himself in – and The Phoenician Scheme‘s style is exposing him. Camera angles that support his depiction of himself are exaggerated, almost mocking, and his appearance is constantly marred by messy injuries. In scene after scene, his supposedly hardened nature and business acumen are repeatedly undermined, as every (often pathetic) attempt to trick his business partners into paying for The Gap fails.

And it’s not just Korda. Liesl and, ahem, Bjørn have both hidden themselves in deceptive styles, too, and The Phoenician Scheme picks away at them until they fall apart and their true feelings come spilling out. The тιтular scheme doesn’t receive the French Dispatch or Grand Budapest treatment, either, and is instead made to seem silly and trivial. Over time, the characters seem to wake up to something the audience has probably asked themselves already: Why do we care so much about this?

And so, Anderson conspires against his characters, but for their own good. By exploring the lies we put into our self-presentation and how we can adhere to them so fully that we forget who we are, he puts Korda, Liesl, and Bjorn on a path to living as their true selves. When we reach the ending, with father and daughter impoverished and running a restaurant, The Phoenician Scheme finally feels like what we’ve come to know as a Wes Anderson film.

Coming directly after his four Roald Dahl short films that themselves were unique experiments, I feel like this movie heralds a new chapter in Wes Anderson’s career. The conspiratorial dynamic he’s had with his leading characters might make way for new relationships. But whatever he does next, I have no doubt it’ll be substantively stylish.