In a breakthrough discovery revealing ancient biodiversity and the first human-animal interaction, archaeologists found a collection of Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene animal remains from Wezmeh Cave in the western Zagros Mountains of Iran, near Kermanshah.

View of the cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

View of the cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

The excavation, carried out in 2019 and led by Dr. Fereidoun Biglari, an archaeologist at Iran’s National Museum, yielded more than 11,000 extremely well-preserved faunal remains—one of the richest fossil collections ever found on the Iranian Plateau.

The multidisciplinary research team included zooarchaeologists Hossein Davoudi of the University of Tehran and CNRS researcher Marjan Mashkour, who is also affiliated with the University of Tehran. Their ongoing analyses highlight the site’s archaeological and ecological significance.

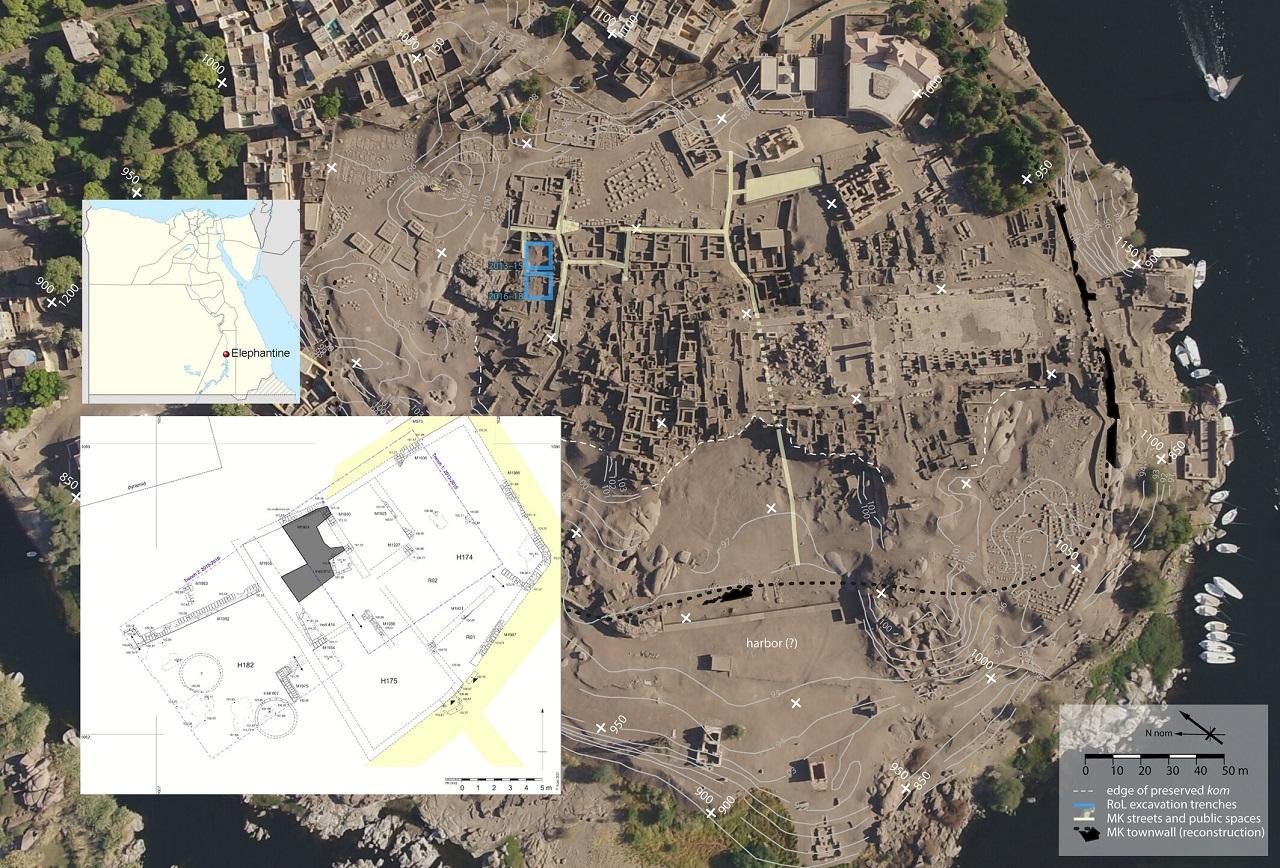

Location of the cave on the map. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

Location of the cave on the map. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

“The very range of taxa from Wezmeh Cave is unlike anything previously documented on the Iranian Plateau,” Dr. Davoudi said. “From large carnivores such as bears and hyenas to domestic sheep and goats, the site preserves a continuous record of faunal transitions spanning tens of thousands of years.”

Test excavation at the rear shaft of the Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

Test excavation at the rear shaft of the Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

The cave has been both a natural trap and a shelter and has accumulated animal remains through carnivore activity, natural mortality, and intermittent human use. “What distinguishes Wezmeh is not just the number of specimens, but the ecological history that they tell,” said Dr. Mashkour. The evidence of burned bones and domesticated animals suggests periodic use of the cave by Neolithic and Chalcolithic herders, indicating a long history of human interaction with the environment.

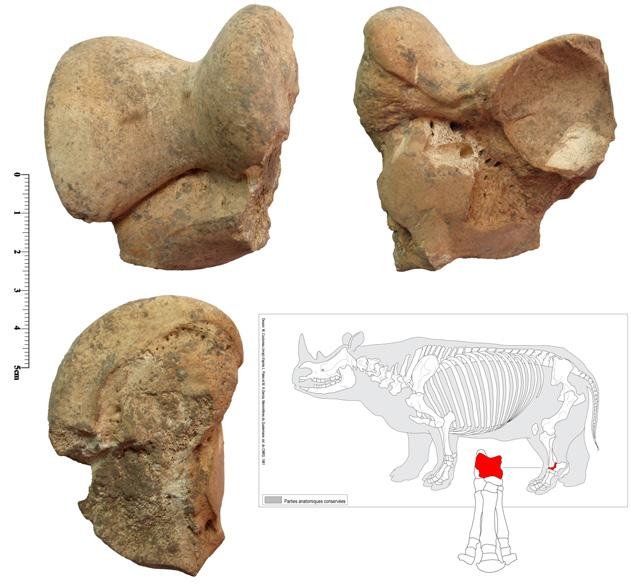

Some of the most significant finds include the remnants of extinct animals such as the cave lion, rhinoceros, aurochs, and the spotted hyena, along with a wide variety of carnivores and herbivores such as brown bears, wolves, foxes, red deer, ibex, wild boars, and equids. The fauna also includes small mammals such as hares, weasels, and porcupines, along with other microvertebrates. These remains span several climatic and cultural phases, providing a unique window into a changing paleoenvironment.

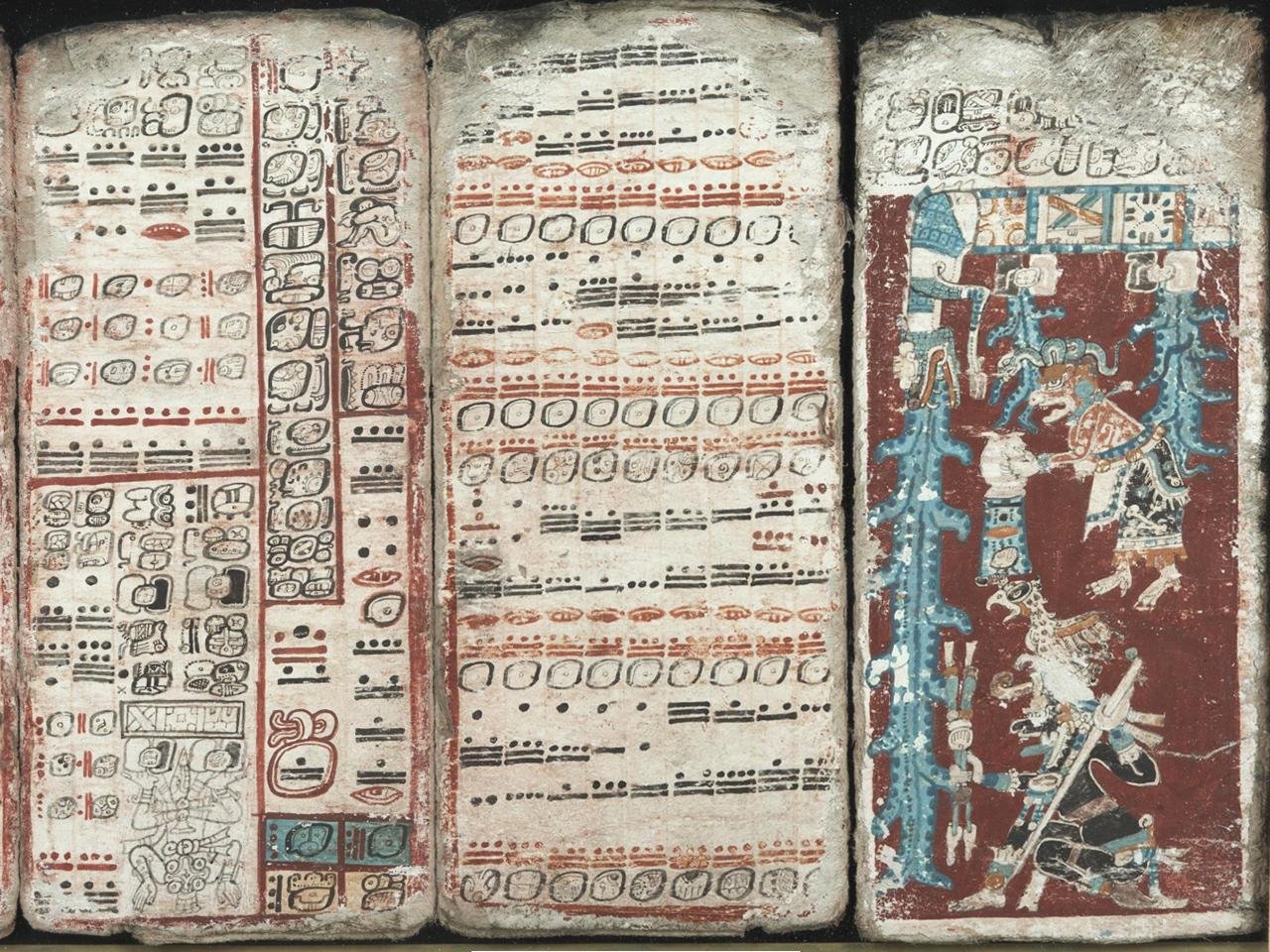

Remains of an extinct rhinoceros species unearthed from the Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

Remains of an extinct rhinoceros species unearthed from the Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

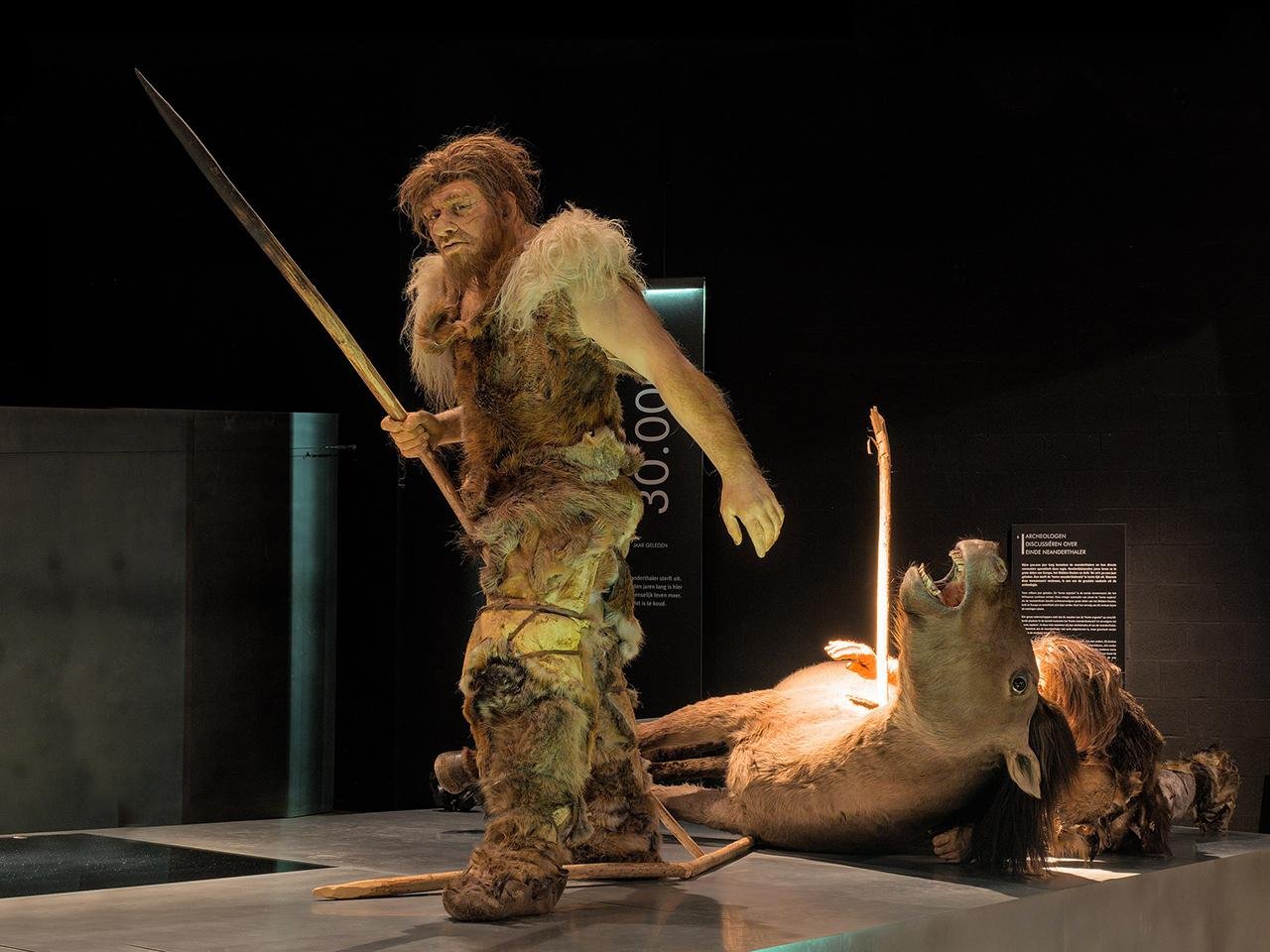

Preliminary taphonomic and archaeozoological studies indicate complex ecological processes and high-level interspecies interaction during different periods. The record of fossils is consistent with earlier discoveries at the site, including the premolar of a Neanderthal child and Early Neolithic pastoralist skeletal remains, which further enhance the significance of the cave as a key archaeological site in Western Asia.

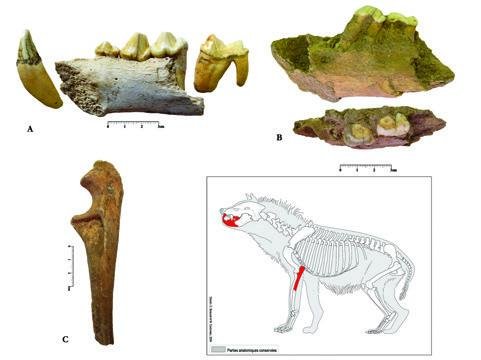

Remains of spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) discovered in Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

Remains of spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) discovered in Wezmeh Cave. Image courtesy of Dr. Fereidoun Biglari

Dr. Biglari pointed to the importance of the discovery for the broader history of human settlement and adaptation in the region. “Wezmeh Cave preserves an unmatched succession of evidence from Middle Paleolithic hunter-gatherer populations to Early Holocene herders,” he explained. “It is one of the richest faunal repositories in Western Asia and offers a key reference point for long-term environmental change and human adaptation.”

More information: Davoudi, H., Mashkour, M., Biglari, F. (2025). Animal Biodiversity during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene in the Zagros Mountains: Evidence from the Wezmeh Cave, Journal of Iran National Museum. doi:10.22034/jinm.2025.2051838.1097