A recently released study is offering a poignant and thought-provoking glimpse into life inside a 14th-century brothel in Aalst, Belgium. Far from the stereotypical tales of neglect and infanticide that have long dominated narratives surrounding medieval prosтιтution, researchers have uncovered compelling evidence of maternal care and emotional bonding inside a bathhouse-turned-brothel.

Detail of the buried infant (AA.OV/161). Credit: PH๏τo by Flanders Heritage Agency / Poulain et al., Archaeol Anthropol Sci (2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Detail of the buried infant (AA.OV/161). Credit: PH๏τo by Flanders Heritage Agency / Poulain et al., Archaeol Anthropol Sci (2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The study centers on the remains of a three-month-old infant that was discovered in 1998 at the historic Nederstove site—an establishment that operated both as a public bathhouse and brothel, common in the medieval Low Countries. The child was buried beneath the loam floor near a hearth used to heat baths, a domestic space that would later be significant in interpreting the emotional context of the burial.

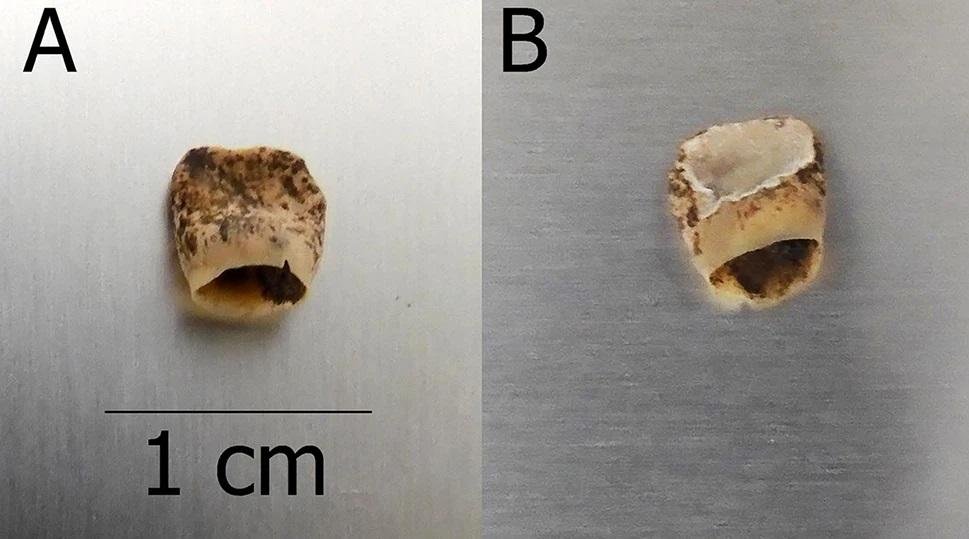

Led by Ghent University’s Dr. Maxime Poulain, with colleagues Céline Bon and Jessica Palmer, the research employed ancient DNA analysis and stable isotope analysis to determine the health and status at death of the infant. Their findings, published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, confirmed that the child was indeed male and actively breastfed—strong indicators that he had not been starved or neglected. Furthermore, there was no evidence of bacterial diseases such as plague, tuberculosis, or cholera.

Dr. Poulain noted that while brothels often appear in medieval records—particularly in the tax documents of the cities of Bruges and Ghent at the time—little is heard about the lives of the women who worked there. This study gives a glimpse into their emotional and maternal lives.

Tooth before (A) and after (B) sampling for ancient DNA analysis. Credit: Poulain et al., Archaeol Anthropol Sci (2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Tooth before (A) and after (B) sampling for ancient DNA analysis. Credit: Poulain et al., Archaeol Anthropol Sci (2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The specific placement of the burial—next to the hearth—also suggests symbolic intent. Medieval folklore held that a soul lingered around the body for a few days after death, and a warm place like the hearth could offer spiritual comfort. One interpretation suggests that “smoldering embers allowed the child to return and warm up at night,” based on then-held beliefs.

In addition, textile remnants in the burial prove the child was shrouded, and therefore indicate respectful and deliberate burial.

Although medieval brothels have traditionally been linked with crime, such as infanticide, this is not the case here. Infanticide at this time would have occurred shortly after birth, but this child was alive for three months and was clearly being cared for. “Infanticide, in the strictest understanding of the term, occurs immediately after birth,” the researchers wrote.

This research not only dismantles the dominant narratives of prosтιтution but also illuminates the complex, multifaceted lives of Sєx workers in medieval society. Rather than portraying these women as either victims or criminals, the research shows us a more nuanced view—a view that recognizes them as mothers who can love and be merciful, even in an unmerciful world.

More information: Poulain, M., Bon, C. & Palmer, J. (2025). Born in a brothel: new perspectives on childcare with medieval Sєx workers. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 17, 105. doi:10.1007/s12520-025-02218-2