Archaeologists from Cotswold Archaeology revealed significant Roman artifacts at the Centre Severn development site in Barnwood, Gloucester, giving new insights into life and construction practices under Roman occupation in Britain. Excavations between September 2020 and February 2021 revealed the remains of a mᴀssive Roman settlement dating from the 2nd to 4th centuries CE, and a remarkably preserved limekiln—perhaps the first of its kind to be excavated in Gloucestershire.

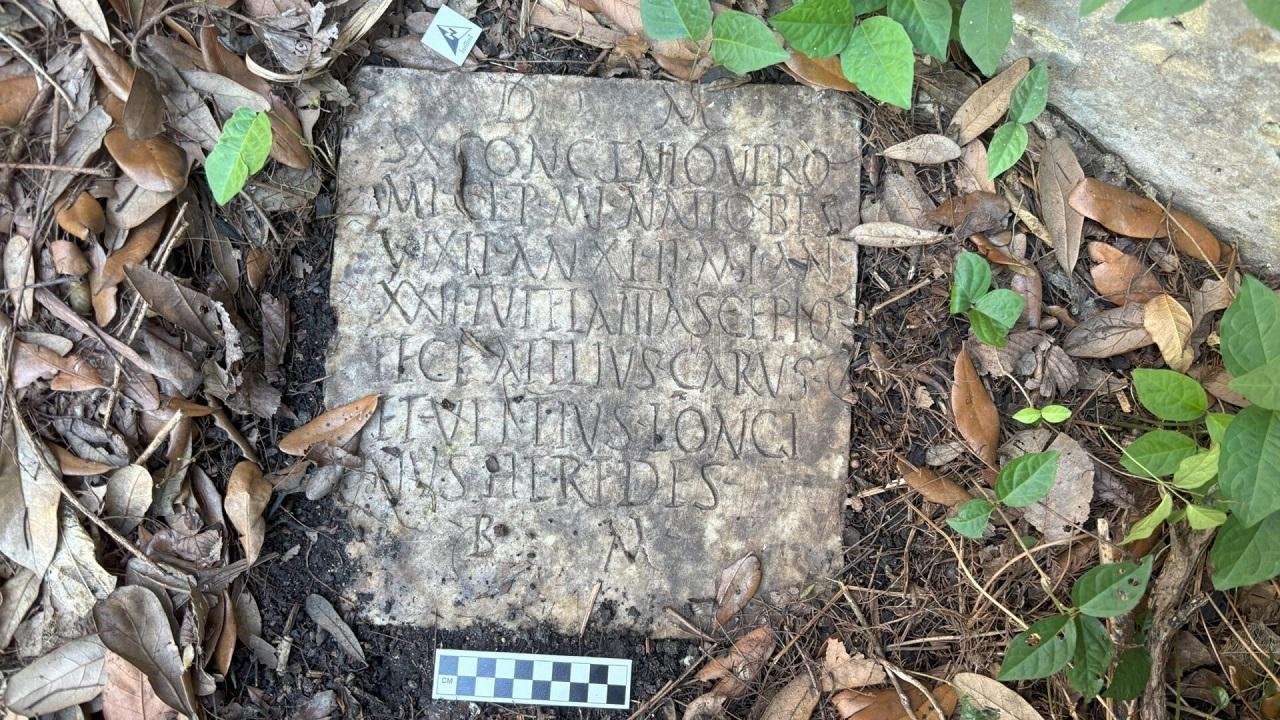

A deliberate dump of Roman pottery. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

A deliberate dump of Roman pottery. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

The site, along Horsbere Brook, a tributary of the River Severn, had long shown potential for archaeological finds. Preliminary geophysical surveys and trial trenches indicated buried features beneath the ground. Full excavation confirmed the theory, with field boundaries, enclosures, two Roman buildings, and even an adult woman’s grave, radiocarbon-dated to between CE 226 and CE 336. The grave was surprisingly sparse, containing nothing but hobnails—presumably from the footwear she was buried in.

A focal point for the excavation is a huge Roman limekiln four meters in diameter and two meters tall. Made of blockstones mortared into the clay, it features a central ledge and a parтιтion wall for improved airflow—features which were designed to improve the lime-burning process. Limekilns like this were used to produce quicklime, one of the critical ingredients in Roman construction materials like mortar, plaster, and concrete.

Burial of a Roman woman aged 40–44 at the time of her death. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

Burial of a Roman woman aged 40–44 at the time of her death. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

The kiln most likely had a brief operational period before it was abandoned in the 3rd century CE, according to Cotswold Archaeology. Later Roman use, including the cutting of a ditch through the northeast edge of the kiln, testifies to its disuse.

The close positioning of the kiln to the limestone-rich Cotswold Hills and the Forest of Dean, a known timber and coal source, highlights its importance. Experts believe that the quicklime produced here may have been used in building activities in the nearby Roman settlements, including Glevum (present-day Gloucester) and Corinium (present-day Cirencester), and perhaps even in a high-status building revealed only 20 meters from the site in the 1970s.

Another intriguing find was a pit that contained a collection of pottery deliberately placed. According to Cotswold Archaeology, this was likely a form of “structured deposition”—a ritualistic or cultural practice of intentional object burial for religious or symbolic reasons.

Roman limekiln during excavation. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

Roman limekiln during excavation. Credit: Cotswold Archaeology

Apart from its industrial significance, the excavation also reveals a rich picture of Roman life in the Severn Vale—an agricultural landscape dotted with farms and villas. The River Severn was a crucial artery of trade and travel, providing access to natural resources such as fish, birds, and thatch materials, while reclaimed lands were fertile grounds for agriculture and livestock.

The full results are detailed in a technical report and in a forthcoming article in the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, and will also soon be accessible on Cotswold Archaeology’s Reports Online website.

More information: Cotswold Archaeology