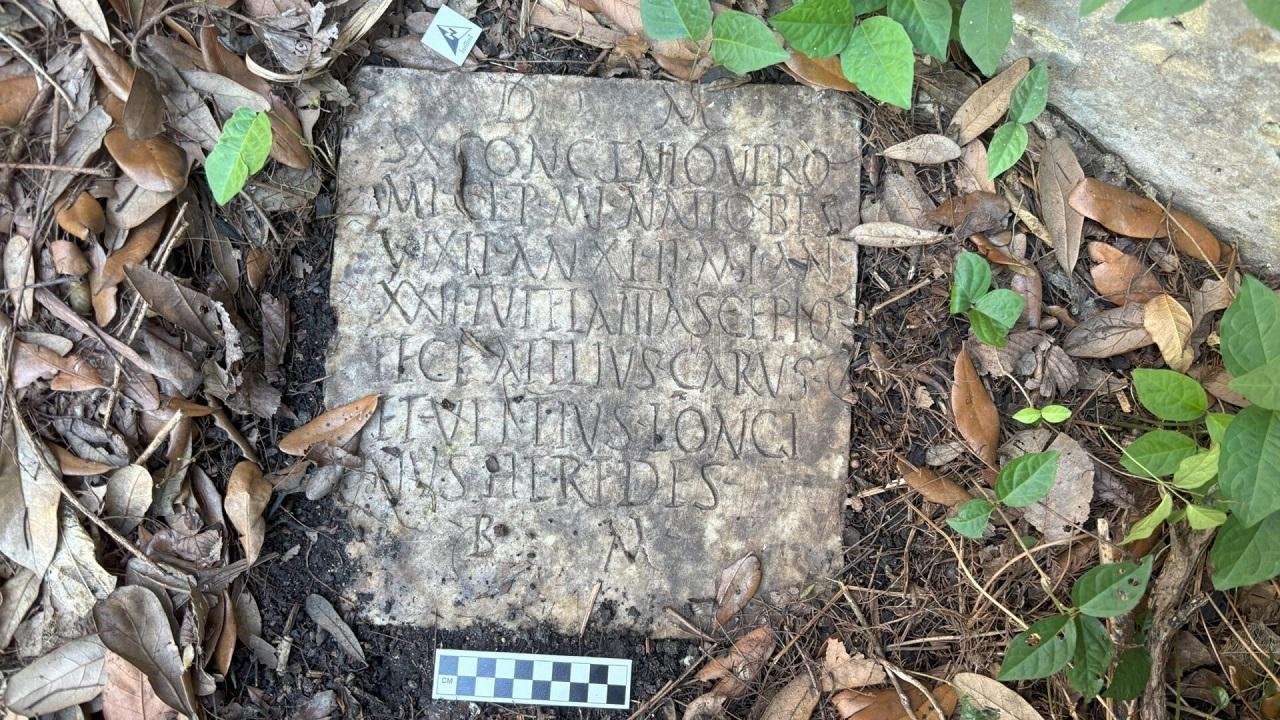

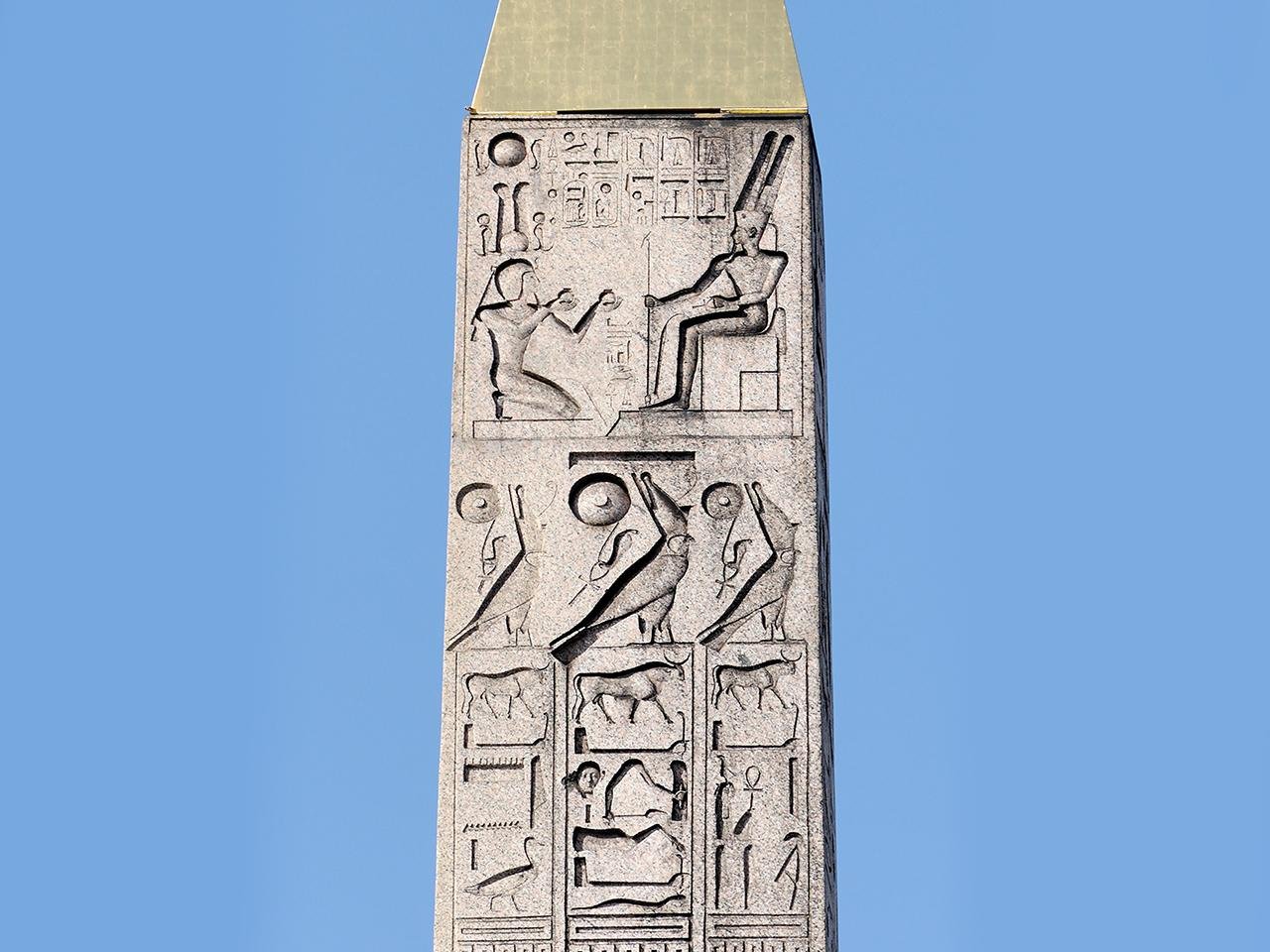

A 3,300-year-old Egyptian obelisk looming over Paris’ Place de la Concorde recently yielded a sequence of secret messages, all thanks to French Egyptologist Jean-Guillaume Olette-Pelletier’s keen observations. Once placed at the Luxor Temple’s entrance in Egypt, the red granite monument is now the target of a groundbreaking study that claims it was an ancient propaganda monument promoting Pharaoh Ramesses II as a divine ruler.

Upper part of the obelisk at the Place de la Concorde, Paris. Credit: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 3.0

Upper part of the obelisk at the Place de la Concorde, Paris. Credit: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 3.0

Originally constructed by Ramesses II—one of the most prolific builders of ancient Egypt—the obelisk was gifted to France by the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century and relocated in 1836. Covered in intricate hieroglyphs, it had been admired for its aesthetic and historical significance. But according to Dr. Olette-Pelletier, who teaches at the Sorbonne and the Catholic University of Paris, the carvings conceal more than meets the eye.

During his regular walks around the obelisk, Olette-Pelletier began noticing unusual patterns within the hieroglyphs. “At one point, I realized something unusual: The hieroglyphs’ meaning indicated a direction, that of the entrance to the portico of the Luxor Temple,” he told Sciences et Avenir. Curious and unable to find previous research on the subject, he decided to investigate further himself.

Entrance to the temple where the obelisk originally stood. Credit: Gérard Ducherm, CC BY-SA 2.5

Entrance to the temple where the obelisk originally stood. Credit: Gérard Ducherm, CC BY-SA 2.5

The breakthrough came in 2021, when scaffolding covered the obelisk for restoration ahead of the Olympic Games. With special permission, Olette-Pelletier climbed the scaffolding to examine the upper parts—usually inaccessible to researchers. The close inspection confirmed that the monument carries a total of seven crypto-hieroglyphs—a rare form of encoded text discovered in the 1950s by Canon Étienne Drioton. These cryptic inscriptions, which typically feature puns, visual wordplay, and varying directions of reading, were meant only to be understood by Egypt’s intellectual elite.

These secret messages, according to Olette-Pelletier, would have been legible to nobles arriving by boat on the Nile, especially to those attending an annual Opet Festival honoring the god Amun. The side of the obelisk that once faced the river (now the Seine) was built so carefully that only from specific angles were the inscriptions readable—including one that even needed to be viewed from a 45-degree angle.

The Obelisk of Luxor at the center of Place de la Concorde, Paris. Credit: Craig Booth, CC BY 2.0

The Obelisk of Luxor at the center of Place de la Concorde, Paris. Credit: Craig Booth, CC BY 2.0

One of the inscriptions contains a depiction of Ramesses II presenting offerings to Amun, with inscribed text declaring the divine origin and eternal right to rule of the king.

One striking example of this three-dimensional cryptography is an engraving that, when viewed from one direction, spells out Ramesses II’s full throne name. When viewed from another, it proclaims his eternal life. Another inscription, once overlooked by scholars, shows an offering table beneath the god Amun, completing a sentence that reads as a sacred offering from the king to the deity.

Place de la Concorde and the obelisk as seen from the Eiffel Tower, Paris, France. Credit: Cristian Bortes, CC BY 2.0

Place de la Concorde and the obelisk as seen from the Eiffel Tower, Paris, France. Credit: Cristian Bortes, CC BY 2.0

Though the discovery has caused excitement, some researchers have urged caution. Since the study is not yet peer-reviewed, they are urging more analysis. Still, the consequences are significant. If confirmed, Olette-Pelletier’s findings not only shed light on how the ancient Egyptians used monumental art for ideological purposes but also on how rulers like Ramesses II upheld power by controlling public imagery.

His full findings are expected to be published in the Egyptology journal ENiM.