“It brings great pride and joy for people to be able to see themselves included in the history of the world”. Especially when it is true. Unfortunately today some faces must be removed from history for others to shine… That’s why representation matters. Accurate representation matters. Queen Hatshepsut was a dark skinned African woman, like all the members of her family. They carried the beautiful dark brown complexion still carried by the majority of African women today. It is time to do the right thing…

Were the Ancient Egyptians Black?

There is a lot of public controversy over which “race” the ancient Egyptians belonged to. Western media has traditionally portrayed nearly all ancient Egyptians as having white skin. Unfortunately, some films are still portraying the Egyptians this way; the 2014 film Exodus: Gods and Kings and the 2016 film Gods of Egypt both received widespread criticism for the fact that nearly all the lead roles were played by white actors.

Nevertheless, I think that, with a few exceptions, nowadays, most people realize that the idea of the ancient Egyptians as almost entirely what we consider “white” is nothing but a racist fantasy. A great deal of controversy still rages, though, over whether the ancient Egyptians were what we consider “black.” A number of authors have tried to argue that ancient Egypt was exclusively or primarily a “black civilization” and that the ancient Egyptians defined themselves as “black people.”

Since the skin color of the ancient Egyptians is a matter of such great controversy, in this article, I want to take a thorough and honest look at the evidence. In this article, we will examine evidence from Egyptian iconography, from Egyptian mummies, from ancient Greek descriptions of the Egyptians, from genetics, and from the conquests and migrations of recorded history. We will discover that Egypt has always been a very ethnically diverse place and that the ancient Egyptians cannot be uniformly classified as belonging to any particular “race.”

First, a little qualification about “race”

People in ancient times did not think of race in the same way that we do. In the twenty-first century, we define “race” in terms of skin color, but, in the ancient world, the concept of skin-color-based racial classification did not exist. The concepts of a “black race” and a “white race” would be totally foreign to them. People recognized that some people had light skin and other people had dark skin, but they didn’t see these things as defining racial characteristics.

Instead, people in the ancient world thought in terms of what we would call “nationalities.” The ancient Egyptians thought of themselves as Egyptians, not “black people” or “white people.” Likewise, all the other peoples of Africa thought of themselves as belonging to whatever nation they belonged. For instance, the people of the Kingdom of Kush thought of themselves as Kusнιтes, not “black people.”

If you walked up to a random man on the street in the Egyptian city of Waset (i.e. “Thebes”) in the fourteenth century BC and asked him, “Are you a member of the black race?” he would be totally confused and he would have no idea what you were talking about. It would be like asking someone on the street today with olive-colored skin, “Are you a member of the olive race?”

The ideas of a “white race” and a “black race” were invented in modern times in order to justify the enslavement of people of African descent by people of western European descent. These concepts are based on extremely superficial physical characteristics and they are scientifically meaningless; anthropologists now regard racial divisions as a cultural phenomenon, not a biological one.

When we apply modern racial divisions to the ancient world, it is very important that we realize that this is deeply anachronistic and that we are applying labels to people that they never would have used themselves and that have no real scientific meaning. Unfortunately, because racial divisions based on skin color are so utterly dominant and inescapable in modern culture, we find ourselves forced to apply them to the ancient world.

ABOVE: Illustration from c. 1854 depicting white slave traders inspecting a black slave in preparation for the slave to be sold. The concepts of a “white race” and a “black race” were created in modern times primarily in order to justify the enslavement of people of African descent. Such concepts did not exist in antiquity.

A little clarification

I also want to clarify that this article is not about the question of whether there were people in ancient Egypt whom we would consider “black.” There were undoubtedly many people in ancient Egypt whom we would consider “black,” just as there are many people in Egypt today who are considered “black.”

One example of a man who lived in ancient Egypt who was definitely what we would consider “black” is Maiherpri, a powerful Egyptian nobleman who lived during the reign of Thutmose IV (ruled 1401 – 1391 BC or 1397 – 1388 BC) and was buried after his death in the Valley of the Kings in tomb KV36.

Maiherpri’s copy of the Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ contains an illustration depicting him with black skin, rather than the usual brown skin that most Egyptians are depicted with in manuscript illustrations. His actual mummy, meanwhile, shows that he did indeed have naturally dark skin. His mummy also bears a wig of curly black hair, which is undoubtedly meant to represent the natural hair that he had when he was alive.

ABOVE: Illustration of Maiherpri from his copy of the Book of ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, showing him with black skin

ABOVE: PH๏τograph of Maiherpri’s mummy, which has naturally dark skin and a wig of frizzy hair that is evidently meant to represent the hair he really had when he was alive

Another famous example of an ancient Egyptian who was definitely what we would consider “black” is Lady Rai (lived c. 1560 – c. 1530 BC), who was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Ahmose-Nefertari. After her death, she was buried in a tomb at Thebes. Her mummy is one of the best preserved Egyptian mummies we have and it clearly reveals that she had naturally dark skin. Her elaborately braided hair is also preserved.

The problem is that many Afrocentrists have tried to go beyond saying that there were people in ancient Egypt whom we would consider “black” and have tried to claim that ancient Egypt was mostly or even exclusively a “black civilization,” that the ancient Egyptians defined themselves as inherently black, and even that all black people are descended from the ancient Egyptians.

None of these things are true.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph of Lady Rai’s mummy, which has dark skin and elaborately braided hair

The name “Kemet”

Proponents of the view that ancient Egypt was an exclusively black civilization and that the ancient Egyptians defined themselves as black have claimed that the ancient Egyptians called their country “Kemet,” which they claim means “Land of the Black People.” Many of them further claim that this name referred not just to Egypt itself, but to the entire continent of Africa as a whole and that all black people are therefore Egyptians and people who are not black have never been true Egyptians.

Contrary to these ᴀssertions, the ancient Egyptians did not call the continent of Africa “Kemet.” The ancient Egyptians do not seem to have had a name for the entire African continent. The Egyptians did, however, refer specifically to the land around the Nile River in which they themselves lived using the name “Kmt,” which is written in hieroglyphics as follows:

The ancient Egyptians did not normally write using vowels, so we don’t know what the vowel sounds in the word “Kmt” were. Modern scholars have inserted the letter ⟨e⟩ between the consonants in order to make the name pronounceable in English, but we really don’t know exactly what the vowel sounds were. In modern Coptic Egyptian, the name for Egypt is ⲭⲏⲙⲓ (Khēmi), which comes directly from Ancient Egyptian “Kmt.”

The name “Kmt” literally means “the black land.” This name almost certainly refers to the extremely fertile black soil that is found in the areas around the Nile River. The ancient Egyptians frequently contrasted the fertile “black” soil of the lands where they lived with the barren “red” sands of the desert that surrounded them. The ancient Egyptian name for the desert was dšṛt, which literally means “the red land.”

Contrary to what the Afrocentrists have ᴀsserted, the name “Kmt” is almost certainly describing the land itself, not the color of the skin of the people who lived there. The ancient Egyptians did not define themselves in terms of their skin color and, as we shall see in a moment, there was, in fact, a great deal of variation in skin tone in ancient Egypt, just as there is in Egypt today.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph of Egyptian soil. The soil is extremely dark because it is extremely fertile.

How the ancient Egyptians thought about skin color

Today, we generally think of skin color as marking a person’s ethnicity, but the ancient Egyptians generally did not think about skin color in the same way that we do. Instead, in ancient Egypt, skin color was widely seen not as a marker of ethnicity, but rather as a marker of gender. In ancient Egyptian art, Egyptian men are usually shown with brown or red skin and Egyptian women are usually shown with white or light brown skin.

The use of different skin colors to signify men and women is a convention that is found in the art of the other cultures in the ancient eastern Mediterranean world as well. Notably, the ancient Minoans used the exact same artistic convention to signify gender; in Minoan frescoes, men are usually shown with brown skin and women are usually shown with white skin.

The reason why the Egyptians and so many other ancient peoples did this is because women in the ancient world were generally expected to stay inside most of the time and remain pale, while men were expected to spend more time outside and become tanned.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a set of painted limestone statues dating to between c. 2649 and c. 2609 BC depicting Prince RaH๏τep and his wife Nofret. Notice that RaH๏τep, the man, is portrayed with brown skin and Nofret, the woman, is portrayed with white skin.

ABOVE: Painting from the burial chamber of Nefertari, dating to between c. 1298 and c. 1235 BC, depicting Amenтιт, the goddess of the west, sitting beside the sun-god Ra. Notice that Ra, who is male, has darker skin than Amenтιт, who is female.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a Minoan fresco from Knossos dating to the middle of the fifteenth century BC depicting a man leaping over a charging bull while one woman seizes the bull by the horns and another woman stands behind the bull with arms outstretched. Notice that the women have white skin while the man has brown skin.

A more cautious look at how Egyptians are portrayed in their art

In addition to gender, all sorts of other societal ideas and artistic conventions affect the way that human beings are portrayed in ancient Egyptian art. We have very few artistic depictions from ancient Egypt from before the Hellenistic Era that can be reliably said to represent a particular person in a detailed and realistic manner.

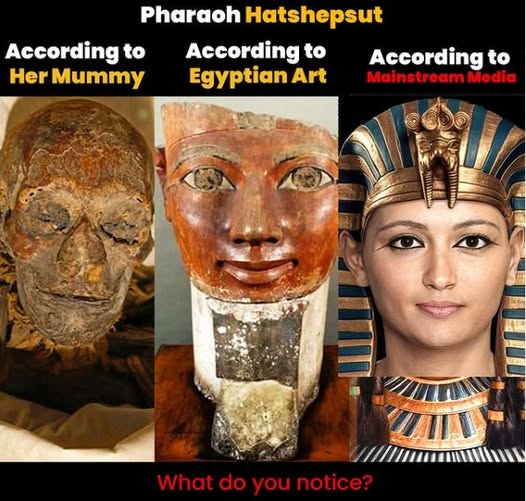

Because the color of a person’s skin in any work of ancient Egyptian art often has more to do with artistic conventions than with the actual color of that person’s skin in real life, it can be dangerous to use ancient Egyptian art as a guide to what color skin people in ancient Egypt really had.

Nonetheless, we should take note that, in works of ancient Egyptian art where the original colors have been preserved, Egyptians are usually portrayed with skin in varying shades of brown. The men generally tend to have darker brown skin and the women generally tend to have lighter brown skin, although this is not always necessarily the case.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a painting of a man hunting from the tomb of Nebamun at Waset (i.e. “Thebes”), dating to c. 1350 BC or thereabouts

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a painting of female musicians and dancers from the tomb of Nebamun at Waset, dating to c. 1350 BC or thereabouts

Meanwhile, in a few surviving works of ancient Egyptian art, brown-skinned Egyptians are contrasted with black-skinned Nubians. This shows that, despite the range of skin colors that certainly existed in ancient Egypt, the ancient Egyptians generally seem to have thought of themselves as having brown skin and the Nubians to the south as having black skin.

A number of frescoes from the tomb of Seti I (ruled 1290 – 1279 BC) paired with the text of the Book of Gates depict various peoples of the ancient world as the Egyptians imagined them. Among the peoples depicted in the frescoes we see a stereotypical Nubian with black skin, a stereotypical Egyptian with brown skin, and a stereotypical southwest Asian with white skin.

The temple built by Rameses II (ruled 1279 – 1213 BC), the most famous Egyptian pharaoh, at the site of Beit el-Wali, included a number of paintings depicting Rameses II’s conquest and subjugation of the Nubians. In these wall paintings, some of the Nubians are portrayed with black skin and others with brown skin, while the Egyptians are portrayed only with brown skin.

Once again, it is important to emphasize that these representations are conventional ones rooted in stereotypes that the Egyptians had about how people belonging to various nations were supposed to look and they probably do not accurately reflect how all people belonging to those nations actually looked. Nonetheless, they do at least tell us how the Egyptians saw themselves in relation to the other peoples of the ancient world.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a painting from Rameses II’s temple at Beit el-Wali depicting the brown-skinned pharaoh charging in his chariot against his Nubian enemies, who are portrayed with both brown and black skin

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of another painting from Rameses II’s temple at Beit el-Wadi depicting subjugated Nubian peoples bearing tribute to the Egyptian pharaoh

ABOVE: Nineteenth-century illustration of a Book of Gates fresco from the tomb of Seti I (ruled 1290 – 1279 BC), showing (from left-to-right) a stereotypical pale-skinned Libyan, a stereotypical black-skinned Nubian, a stereotypical pale-skinned southwest Asian, and a stereotypical brown-skinned Egyptian

The famous bust of Neferтιтi

Proponents of the view that all ancient Egyptians were black are constantly insisting that the famous bust of Queen Neferтιтi currently held in the Neues Museum in Berlin must be a fake because it portrays Neferтιтi with pale skin. They’ve tried to come up with all sorts of other arguments for why it must be a fake, with one of them being that the bust is too well-preserved to be over three thousand years old.

None of these arguments hold up to any scrutiny; there are plenty of other representations of Egyptian women with pale skin and there are plenty of works of art that are even older than the Neferтιтi bust that are just as well preserved.

In reality, the bust is almost certainly authentic, but its authenticity is largely irrelevant to the question of what skin colors people in ancient Egypt had, since it is clearly an example of the standard Egyptian convention of portraying women with pale skin as a marker of their femininity.

As is the case with most works of Egyptian art from before the Hellenistic Period, the Neferтιтi bust tells us a lot more about the conventions of ancient Egyptian art than it does about Neferтιтi’s actual appearance.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of the famous bust of Queen Neferтιтi in the Neues Museum in Berlin, which probably tells us a lot more about the conventions of Egyptian art at the time than it does about Neferтιтi’s actual physical appearance

Evidence from mummies

Pretty much all surviving representations of Egyptians from before the Hellenistic Period are heavily conventionalized, which makes it hard to judge how well they reflect the actual appearance of the people they are supposed to represent. They certainly provide us with information about how the ancient Egyptians imagined themselves, but, in most cases, they do not provide us with detailed information about what real individuals looked like.

In the absence of realistic portraits of specific individuals from the pharaonic period, we can instead look at people’s mummies, which can give us some information about what these people looked like when they were alive. Nevertheless, we need to be careful about using mummies as evidence because oftentimes people’s mummies look very different from how the people looked when they were alive.

Mummies’ facial features have often been damaged or distorted either by the embalming process itself or by deterioration after embalming. Many mummies have wigs instead of natural hair and, when they do have natural hair, it is often dyed. Meanwhile, the chemicals used in embalming can sometimes change the color of a person’s skin, making it appear darker or lighter than it would have appeared when the person was alive.

One of the most famous surviving mummies from ancient Egypt is the mummy of Rameses II. From a superficial glance at Rameses II’s mummy, it appears as though he had splotchy brown skin and wavy reddish-blond hair. Things are more complicated than they seem, though. A forensic analysis published in 1987 concluded that Rameses II’s skin has actually been unnaturally darkened due to the chemicals that were used for his embalming and that his natural color would have been significantly lighter.

Meanwhile, the analysis also concluded that his hair was naturally white at the time of his death, since he was about ninety years old at the time. His hair only appears reddish-blond on his mummy because it has been dyed that color with henna. Nonetheless, the analysis concluded that his hair was naturally red when he was a young man and that either Rameses II himself or his embalmers had dyed it red in effort to make it look the way it had when he was younger.

The fact that Rameses II evidently had relatively light skin and wavy red hair illustrates that there evidently were some people in ancient Egypt who were what we would consider “white.”

ABOVE: PH๏τograph of the mummy of Rameses II. He had white hair at the time of his death and his hair only appears red here because it has been dyed with henna. Nonetheless, a forensic analysis of his hair concluded that he really did have red hair when he was a young man.

Ancient Greek descriptions of the Egyptians

Proponents of the view that ancient Egypt was an exclusively or predominately “black” civilization have also tried to point to descriptions of the Egyptians written by Greek authors. They claim that these descriptions clearly characterize the Egyptians as black people. The evidence, however, is a lot less clear-cut than the Afrocentrists claim.

For instance, the Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnᴀssos (lived c. 484 – c. 425 BC) says in his Histories 2.104 that he knows that the people of the land of Kolchis (located in what is now western Georgia) are of Egyptian descent in part because the people of Kolchis and Egypt are both “μελάγχροες… καὶ οὐλότριχες,” which means “dark-skinned and curly-haired.” This line is often quoted by Afrocentrist writers with the mistranslation “black-skinned and curly-haired.”

This translation, though, is certainly inaccurate; the word μελάγχροες comes from the Greek word μέλας (mélas), which just means “dark.” Sometimes this word can mean “black,” but it does not inherently mean “black” and the word is often used to describe anything that is of a generally dark color. The word μελάγχροες could therefore refer to anyone with skin that is any color from light brown to completely black.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of an ancient Roman marble copy of a Greek bust of the historian Herodotos of Halikarnᴀssos, who described the Egyptians as “μελάγχροες… καὶ οὐλότριχες”

Greek stereotypes about the Egyptians

Furthermore, we must absolutely bear in mind at all times that the descriptions we are given in ancient Greek sources of what the ancient Egyptians supposedly looked like reflect a stereotype of how ancient Greek writers imagined the appearance of the Egyptians. When Herodotos says that the Egyptians—or any other people for that matter—look a certain way, it would be a grave error to interpret what he says as an accurate description of all people belonging to that particular nationality, or even necessarily the majority of people belonging to that nationality.

Indeed, ancient Greek writers are rather notorious for stereotyping what people of a certain culture were supposed to look like based on features that weren’t even necessarily held by the majority of the population. For instance, Greek writers stereotyped the peoples of the land of Thrake, located northeast of mainland Greece, as having reddish blond hair and blue eyes.

Nevertheless, we know that this stereotypical appearance doesn’t hold true for all Thrakians or even the majority of Thrakians. It seems that the Greeks simply noticed that reddish blond hair and blue eyes were relatively common among the Thrakians compared to other peoples of the eastern Mediterranean and therefore began stereotyping the Thrakians in this manner.

The same thing is probably true for ancient Greek descriptions of the Egyptians. Clearly, Herodotos and other Greeks noticed that some Egyptians had dark skin and curly hair and they decided that this was the “standard” appearance of an Egyptian person.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of part of a fresco from an ancient Thrakian tomb from a site near Kazanlak, Bulgaria. The ancient Greeks stereotyped Thrakians as having reddish blond hair and blue eyes, but not a single person in this whole fresco actually has red hair.

A word of caution about genetic studies

Now that we’ve talked about evidence from Egyptian iconography, evidence from mummies, and evidence from ancient Greek descriptions, we need to talk about evidence from genetics. This is the evidence that usually tends to dominate the conversation. As I discuss in this article I wrote in February 2020 about the relationship between modern and ancient Greeks, though, we should really be extremely cautious of any sweeping claims made about the ethnicity of ancient peoples based on genetic evidence because genetics don’t work the way that most non-geneticists think they do.

Companies like 23andMe and Ancestry have irresponsibly portrayed genetics as though a simple genetic test can tell you the exact percentage of your total genome that comes from ancestors of a specific nationality. In reality, the vast majority of genes are found in people of all nationalities and there is always much greater genetic diversity among individual people of any particular nationality than there is between the people of two different nationalities collectively.

What genetics companies actually rely on are genetic markers—a handful of genes found within a person’s larger genome that generally tend to be ᴀssociated with members of a certain reference population with documented ancestors from a certain part of the world.

These genetic markers aren’t always totally reliable, since, in many cases, the same mutation may have occurred in several different parts of world at different times and may be ᴀssociated with people of totally different backgrounds. For instance, the MTHFR C677T mutation is a genetic marker that is common in people of Mexican ancestry, but also in people Chilean, Chinese, and Italian ancestries. It is also less commonly found in other populations of people from all over the world, including western Europe, Britain, Ireland, and Colombia.

If a geneticist examines the DNA from someone who has the MTHFR C677T gene, they have no way of knowing just from looking at the mutation itself whether the person inherited that mutation from an Italian ancestor, a Chinese ancestor, a Mexican ancestor, a Chilean ancestor, or some other ancestor.

When a personal genome company tells you that you are a certain percent “from” a certain region, what they really mean is that that percentage of the genetic markers they identified within your larger genome are often ᴀssociated with members of a reference group composed of people with known ancestry in that part of the world. Genetic evidence can be useful, but we need to be very careful with it because, when it comes to genetics, things are a lot more complicated than most people realize.

ABOVE: ScreensH๏τ from an advertisement for a DNA ancestry test from Ancestry.com, showing a man looking surprised to find out “52%” of his DNA comes from “Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.” What that percentage really means is that 52% of the genetic markers the analysts found in his DNA are often ᴀssociated with reference populations of people with known ancestry in that part of the world.

A further word of caution about genetic evidence and ancient Egypt

Things get especially complicated when we start talking about genetics in ᴀssociation with ancient Egypt, since Egypt is a geographically large country with a historically diverse population. Ancient Egyptian history also spans the course of roughly four thousand years, from the rise of Egyptian civilization in the late fourth millennium BC to the conquest of Egypt by the Rashidun caliphate in the seventh century AD. Egypt’s population has, naturally, changed to some extent over the course of its long history.

Unfortunately, people seem to have a very pernicious habit of making grand, sweeping claims about the ancient Egyptians’ supposed “race” based on extremely limited genetic evidence. Both Eurocentrists who want to believe that the ancient Egyptians were all what we would consider “white” and Afrocentrists who want to believe that the ancient Egyptians were all what we would consider “black” are guilty of this.

To give an especially ludicrous example of how genetic evidence has been distorted and misused, in August 2011, a Swiss personal genomics company called iGENEA claimed—supposedly based on an extremely small portion of Tutankhamun’s Y-chromosome DNA that was allegedly shown on screen in a Discovery Channel documentary—that Tutankhamun belonged to certain haplogroups that they claimed include more than half of all men in western Europe.

iGENEA’s already dubious claims became even more distorted and exaggerated in the press. The National Post ran an article with the headline “King Tut DNA more European than Egyptian.” The Daily Mail ran an article with the headline “We’ve got the same mummy! Up to 70% of British men are ‘related’ to the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun.”

Soon ordinary people who read these headlines were saying that a study had proven that the ancient Egyptians were ethnically western Europeans. The problem is that there wasn’t even a real genetic study at all; the whole story was born from a single genetics company claiming something about one pharaoh’s DNA based on what they thought was a portion of that pharaoh’s Y-chromosomal DNA that had been inadvertently shown on screen in a Discovery Channel documentary.

In fact, the actual researchers who had extracted and decoded Tutankhamun’s DNA denounced iGENEA’s conclusions, saying that the company had acted irresponsibly and unscientifically and that they had misinterpreted the data that had been shown on the screen in the Discovery Channel documentary. Carsten Putsch, one of the geneticists involved in the original project, told LiveScience that iGENEA’s conclusions were “simply impossible.”

Meanwhile, proponents of the view that all ancient Egyptians were what we would consider “black” have made similarly irresponsible claims based on extremely little evidence, often citing the presence of certain genetic markers that tend to be ᴀssociated with people of sub-Saharan African ancestry in the genomes of certain Egyptian pharaohs as “proof” that all Egyptians were “black.” This, of course, at best only proves that some Egyptian pharaohs had some ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikimedia Commons of a highly conventionalized representation of Tutankhamun and his wife from the back of Tutankhamun’s throne, on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. This is the man that The Daily Mail apparently claims was ethnically British.

ABOVE: PH๏τograph from Wikipedia Commons of a highly conventionalized mannequin of Tutankhamun that was discovered in his tomb

A genetic study on Egyptian mummies published in 2017

A genetic study published in May 2017 in the journal Nature Communications examined DNA samples from a much larger selection of ancient Egyptian mummies than any other previous study had done and concluded that modern Egyptians actually tend to have a much higher number of genetic markers ᴀssociated with people of sub-Saharan African ancestry than the ancient Egyptians did.

The study concluded that the ancient Egyptians had relatively little genetic affinity with modern people of sub-Saharan African ancestry and that, due to the trans-Saharan slave trade that flourished in the Early Modern Period, the presence of genetic markers ᴀssociated with sub-Saharan Africa has dramatically grown in the Egyptian population since the Arab conquest of Egypt in the seventh century.

Remarkably, the study also concluded that the ancient Egyptians whose DNA they analyzed tended to have more genetic markers in common with modern peoples of the Near East than with modern Egyptians. If this study is correct, this means that the exact opposite of what Afrocentrists claim is the truth.

Afrocentrists often claim that the ancient Egyptians were all or mostly what we consider “black” and that modern Egyptians are descendants of the Arab conquerors, but this study suggests that the ancient Egyptians had a close genetic affinity with modern peoples of the Middle East and that modern Egyptians actually have a closer genetic affinity with peoples of sub-Saharan Africa than their ancient ancestors did.

Of course, this study also has some serious methodological limitations. Notably, it only examined DNA samples from 151 mummies, all of which came from the site of Abusir el-Meleq in Lower Egypt. Furthermore, judging from Supplementary Data 1, nearly all of the mummies included in the study seem to have belonged to individuals who lived after 1000 BC.

The fact that all the mummies examined in this study came from the same site in Lower Egypt means we should be very careful about making generalizations based on it. I suspect that, if the study had examined mummies from Upper Egypt, they would have found more genetic markers ᴀssociated with sub-Saharan Africa.

Nonetheless, this was the first genetic study that has ever been conducted using DNA from such a large sample of Egyptian mummies and, despite its very serious limitations, it represents an important step forward in our understanding of the population history of Egypt.

ABOVE: Map from Wikimedia Commons showing the findings of the 2017 genetic study, which concluded that ancient Egyptians from the site of Abusir el-Meleq in Lower Egypt had the most genetic markers in common with modern peoples of the Near East and that they had relatively little genetic affinity with modern sub-Saharan Africans

Realistic portraits of ordinary people from Lower Egypt from the Hellenistic and Roman periods

Images of people from the early periods of Egyptian history are highly conventionalized and they do not normally portray the specific details of the appearances of individual people. Mummies can be misleading, since the process of embalming can change a person’s appearance significantly. Greek sources describing the Egyptians’ appearance are largely based on stereotypes. Finally, genetic studies on ancient Egyptian remains are limited.

Our sources for what people during pharaonic times looked like, then, is complicated to say the least. They do, however, give us a general picture of what Egypt looked like during the time of the pharaohs: an eastern Mediterranean country with a diverse population of people, the majority of whom seem to have had brown skin, but substantial minorities of whom seem to have had darker or lighter skin tones.

Once we start getting into the Hellenistic Period (lasted c. 323 – c. 31 BC) and Roman Period (lasted c. 31 BC – c. 646 AD) of Egyptian history, though, we finally start to get realistic portraits of what real people looked like when they were alive. In particular, we have a pretty good impression of what people from Lower Egypt during the Hellenistic and Roman Periods looked like thanks to the wealth of highly detailed, realistic encaustic panel portraits that have survived from the region from these periods of Egyptians history.

These are funerary portraits that originally covered the faces of the mummified bodies of the individuals they depict. They are conventionally known as the “Fayum mummy portraits” because many of them were found at sites located near the Fayum Basin in Lower Egypt. They depict ordinary people from the upper and middle classes. Here are a few examples:

ABOVE: Portrait of a young woman from the city of Antinopolis in Lower Egypt dating to around the second or third century AD or thereabouts

ABOVE: Portrait of a young military officer from Lower Egypt, dating to the time of the Roman Empire

ABOVE: Portrait of a young man from the city of Antinopolis in Lower Egypt dating to around the second or third century AD or thereabouts

ABOVE: Portrait of an elderly Egyptian man from the Roman period

ABOVE: Portrait of a young man from the site of Hawara in Lower Egypt

ABOVE: Portrait of a woman dating to the early second century AD

ABOVE: Portrait of a military officer from Lower Egypt from the middle of the second century AD

ABOVE: Portrait of an Egyptian man from the Staatliche Museum in Berlin

ABOVE: Portrait of an Egyptian woman dating to the late second century AD

ABOVE: Portrait of a young man from Fayum dating to around the second or third century AD or thereabouts

ABOVE: Portrait of a woman from Lower Egypt dating to around the late second century AD or thereabouts

ABOVE: Portrait of a man from Fayum, dating to around the mid-second century AD or thereabouts

These portraits reflect the incredible diversity of people that existed in Egypt during the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. In these portraits, we see real, ordinary people with all different colors of skin who lived in Egypt during this time period.

This is the way Egypt has always been and the way it still is today: a place with people of diverse backgrounds and diverse colors of skin. Literally any one of these people could easily pᴀss as a modern Egyptian.

The population of modern Egypt

The modern population that is most directly descended from the population of ancient Egypt is the population of modern Egypt. Modern Egyptians have a range of different skin tones; some have pale skin, others have dark skin, but the majority generally tend to have brown skin. All the evidence we have just examined indicates that the ancient Egyptians exhibited the same range of skin tones.

It is true that Egypt was conquered by the Arabs in the seventh century AD. It is also true that most modern Egyptians are Muslims who speak Arabic, but this doesn’t mean that modern Egyptians aren’t descendants of the ancient Egyptians. As I discuss in this article about whether modern Greeks are related to the ancient Greeks, once you go back to ancient history, matters of ancestry get really complicated. The Arabs conquered Egypt, but they didn’t mᴀssacre the Egyptian population and it is likely that most modern Egyptians have more Egyptian ancestors than Arab ancestors.

Furthermore, it is worth pointing out the existence of modern Coptic Egyptians, who make up somewhere around one twentieth of the population of Egypt. These are people who never converted to Islam and instead have remained Christian to the present day, just like the majority of Egyptians in late antiquity. Historically Coptic Egyptians have been highly endogamous, meaning that, historically speaking, they have generally avoided marrying Muslim Egyptians.

For most of their history, Copts even continued to speak Coptic, a later form of the same Egyptian language that was spoken by the pharaohs of old. Today, Coptic is mostly only used as a liturgical language and most Coptic Egyptians speak Arabic like their Muslim neighbors. Nonetheless, Copts have maintained their own culture and their own religion.

I am not going to say that Copts are “pureblooded” descendants of the ancient Egyptians because there is no such thing as a “pureblooded” descendant of any people who lived over a thousand years ago, but, of all the people in the world, they are the ones who have the closest cultural ties to the ancient Egyptians. It so happens that Coptic Egyptians generally tend to have similar skin tones to Muslim Egyptians. Here is a video from 2011 of thousands of Coptic Christians singing in one of the cave churches near the city of Cairo:

If you look at the people in this video, you will see they are mostly varying shades of brown. This is consistent with how the pharaonic Egyptians generally portrayed themselves in art and how the late antique Egyptians shown in the Fayum mummy portraits are represented.

Egypt’s ever-diverse and changing population

Proponents of the view that ancient Egypt was a primarily or exclusively black civilization like to latch onto the date of the Arab conquest as the date when Egyptians supposedly stopped being black, but they are ignoring the fact that people coming to Egypt from the southwest Asia and even Europe is not at all a recent phenomenon in any sense. From the very earliest period in Egyptian history, we have records of people coming to Egypt from all parts of southwest Asia, especially from Canaan, and even from parts of southern Europe.

As early as the nineteenth century BC, there were already people immigrating to Egypt from Canaan and Syria in mᴀssive numbers. Some of these Canaanites established a territory in the eastern Nile Delta, where they established the Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt, which ruled contemporaneously with the Egyptian Thirteenth Dynasty.

In around the middle of the seventeenth century BC, a people from southwest Asia known as the Hyksos conquered nearly all of Egypt and ruled for about a hundred years before the Hyksos rulers were finally driven out. During the time when Egypt was ruled by Hyksos, it is impossible to imagine that there was no intermarriage between the Egyptians and the ruling people from southwest Asia.

From at least the eighteenth century BC onwards, the Minoans, a people from the Aegean islands, also had a very significant presence in northern Egypt. Many Minoan artifacts have been found in Egypt. The palace at Avaris in the Nile Delta, most likely dating to the reign of Hatshepsut (ruled c. 1479 – 1458 BC) or the reign of her nephew Thutmose III (ruled 1479 – 1425 BC), was even decorated with a large number of frescoes in a distinctively Minoan style, suggesting that the Egyptians employed Minoan artists.

ABOVE: Reconstruction of a Minoan fresco from the palace at Avaris in the Nile Delta, dating to the fifteenth century BC. Peoples from southeast Europe and southwest Asia have had a significant presence in Egypt since the very beginning.

Of course, it is worth noting that, at the same time that there were people coming to Egypt from southwest Asia, there were also large numbers of people coming to Egypt from the south, from what is now Sudan. Indeed, the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Egypt (lasted 744 – 656 BC) was made up of rulers who came from the Kingdom of Kush in what is now modern-day Sudan.

It is also worth noting that, long before the Arab conquest, Egypt was ruled by the Achaemenid Persians from 525 BC to 404 BC and then again from 343 BC to 332 BC. In 332 BC, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great, the king of Makedonia, a kingdom located in northern Greece. After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, Egypt fell under the rule of his general Ptolemaios I Soter, who established a dynasty of Greek rulers that lasted until the death of Cleopatra VII Philopator and the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Empire in 30 BC.

Egypt was ruled by Rome all the way until the Arab conquest. In other words, by the time the Arab conquest happened, Egypt had already been ruled by various foreign nations almost continuously for over a millennium. The Arab conquest, then, is perhaps not such an era-defining event as some people have supposed.

Meanwhile, as noted above, since the time of the Arab conquest, many people from sub-Saharan Africa have been brought to Egypt through the trans-Saharan slave trade. If the genetic study referenced above is correct, this trade has apparently left quite a substantial mark on the present population of Egypt.

None of the foreign nations that have ruled Egypt have ever made any successful effort to exterminate the native population of Egypt. The population of Egypt hasn’t been replaced, but new peoples have moved in and, in some cases, intermarried with members of the local population. There is still direct population continuity from the earliest Egyptians to the Egyptians of the present day.

Modern Egyptians are probably not “pureblooded” descendants of the ancient Egyptians, but it is important to remember that the ancient Egyptians were certainly not “pureblooded” descendants of earlier Egyptians either. Egypt has always been a melting pot with inhabitants from all over the place.

ABOVE: Hellenistic mosaic from the site of Thmuis dating to around 200 BC depicting Queen Berenike II as the personification of the city of Alexandria

Kleopatra VII Philopator’s skin color

The debate over the skin color of the ancient Egyptians has spilled over into debate over the appearance of Kleopatra VII Philopator, the Greek queen of Egypt whom we know in English as “Cleopatra.” In January 2020, when word came out that Angelina Jolie and Lady Gaga were the main contenders for the role of Cleopatra in an upcoming biopic, many people accused the filmmakers of whitewashing, saying that the Egyptian queen should be portrayed by a black actress.

The first problem here is that Cleopatra was not ethnically Egyptian at all; in fact, we know almost her entire family history and, as far as we know, she did not have even a single Egyptian ancestor. Nearly all her ancestors came from the region of Makedonia in northern Greece, bordering on Thrake. Her only known non-Greek ancestor is Apama, the Sogdian wife of her distant ancestor, the Greek king Seleukos I Nikator.

Furthermore, as I discuss in this article I wrote in January 2020 about what Cleopatra looked like, we have a tremendous wealth of surviving depictions of Cleopatra from the time when she was alive and none of them give us any evidence that she was what we would consider “black.”

In fact, there is a fresco from the city of Herculaneum dating to the first century AD that definitely represents either Cleopatra herself or a member of her family as a pale-skinned redhead. Although the fresco certainly represents a queen belonging to the Ptolemaic dynasty and it most likely represents Cleopatra VII, since it closely resembles the known portraits of her found on coins, we can’t be completely certain that it is her and, if it is indeed her, we can’t be completely certain that it is accurate.

Likewise, here too we have to be wary of conventions. The ancient Greeks and Romans also tended to portray women as pale-skinned because pale skin was seen as a marker of feminine beauty. Also, the artist who painted this fresco would have certainly known that the Ptolemies were of Makedonian descent and that Makedonia was in the northern reaches of Greece, near Thrake, meaning we can’t totally rule out the possibility that he may have simply ᴀssumed that Cleopatra had red hair based on Greek stereotypes of northerners.

ABOVE: First-century AD Roman fresco from the city of Herculaneum representing a Ptolemaic queen of Egypt, probably Cleopatra VII, as a pale-skinned redhead

Hypatia of Alexandria’s skin color

There is also some popular contention over the skin color of the Egyptian mathematician Hypatia of Alexandria. I wrote a whole article on this subject in October 2019, but I will summarize the information in that article here.

Hypatia was born at some point in the second half of the fourth century AD and was ᴀssᴀssinated in March 415 AD by supporters of Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria, due to her involvement in a heated political dispute between Cyril and Orestes, the Roman governor of Egypt. (For more information about her life in general, you can read this article I wrote about her in August 2018 or this article I wrote in February 2020, in which I debunk an especially inaccurate portrayal of her in popular culture.)

We have far less information about Hypatia than we do about Cleopatra. All we know about her ethnic background is that she came from Alexandria, which is a city in northern Egypt that was founded in Greeks; both she and her father Theon have Greek names; and both she and her father wrote exclusively in Greek. None of this necessarily means that she was ethnically Greek, though, since many people in Egypt during the Hellenistic and Roman Periods who had no Greek ancestors adopted Greek culture.

We have no surviving ancient depictions of Hypatia and our only surviving description of her physical appearance is a vague statement from the Greek Neoplatonist philosopher Damaskios of Athens (lived c. 458 – c. 538 AD) that she was “exceedingly beautiful and fair of form.”

We have little reason to think that even this description is reliable, though, since Damaskios was not even born until nearly half a century after Hypatia’s death and we have no evidence that he knew anyone who had known her when she was alive. His description of her as extraordinarily beautiful, then, may just be his own male fantasy.

In short, we know almost absolutely nothing about what Hypatia looked like. The best guess is that she probably looked somewhat similar to some of the women shown in the Fayum mummy portraits, which give us a vague impression of what ordinary Egyptian women looked like in the time when Hypatia was alive.

ABOVE: Image of two different modern portrayals of Hypatia that I featured in this article I published in October 2019. In reality, both of these portrayals are fictional. We have no idea what Hypatia really looked like.

Summary and conclusions

The concepts of a “white race” and a “black race” are modern and would be utterly foreign to the ancient Egyptians. Contrary to what some people have claimed, the name “Kmt” does not mean “Land of the Black People” and the ancient Egyptians did not define themselves in terms of their skin color.

Surviving artistic depictions from the pharaonic periods must be treated with caution because they are often highly conventionalized. Nevertheless, they reveal that Egyptians of the pharaonic periods generally tended to portray themselves with brown skin. There are surviving mummies of people in ancient Egypt who would be considered “white,” people who would be considered “black,” and people who fall somewhere in between.

Genetic evidence must be treated with caution, since genetics is a lot more complicated than most people realize. Nonetheless, a genetic study of Egyptian mummies published in 2017 concluded that the people in ancient Egypt—or at least people who lived at the site in Egypt where the mummies came from—had a close genetic affinity with modern peoples of the Near East.

More realistic surviving depictions of people from Egypt from the Hellenistic and Roman Periods portray them with a range of skin colors, but with brown skin being predominate. This same range of colors still exists in Egypt today and, although the population of Egypt has changed, there is still population continuity between the people of Egypt from the very earliest times and the people of Egypt today.