3-D Reconstruction Reveals the Faces of Three Ancient Egyptian Mummies

Researchers used a combination of DNA and physical analysis to approximate the trio’s visages

In a feat seemingly straight out of “The Mummy” movies, DNA is helping researchers reanimate the faces of people who lived more than 2,000 years ago. As Mindy Weisberger reports for Live Science, scientists used genetic information taken from three ancient Egyptian mummies to produce digital images of what the men might have looked like at age 25.

Residents of Abusir el-Meleq, an ancient Egyptian city south of Cairo, the men died between 1380 B.C.E. and 450 C.E. A team from Parabon NanoLabs presented the trio’s facial reconstructions at the International Symposium on Human Identification in September.

“[T]his is the first time comprehensive DNA phenotyping has been performed on human DNA of this age,” says Parabon, a Virginia-based company that typically uses genetic analysis to help solve cold cases, in a statement.

To approximate the men’s faces, researchers used DNA phenotyping, which predicts individuals’ physical appearance based on genetic markers. (Phenotyping can suggest subjects’ skin, hair and eye color, but as Caitlin Curtis and James Hereward wrote for the Conversation in 2018, the process has its limitations.) The team determined the mummies’ other characteristics through examination of their physical remains, reports Hannah Sparks for the New York Post.

Parabon used DNA taken from the mummies in 2017 to create the 3-D images. That earlier study, led by scientists at the Max Planck Insтιтute for the Science of Human History in Germany, marked the first time researchers successfully extracted DNA from ancient mummies—a “tantalizing prospect” long considered “more myth than science,” wrote Ben Panko for Smithsonian magazine at the time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/a8/b0a8a2c1-dd82-4810-9472-8ea02f5aa09e/sarcophagus_tadja_c_aegyptisches_museum_steiss_sandrajpg.jpeg)

“[Scholars] were generally skeptical about DNA preservation in Egyptian mummies, due to the H๏τ climate, the high humidity levels in tombs and some of the chemicals used during mummification, which are all factors that make it hard for DNA to survive for such a long time,” study co-author Stephan Schiffels told Tracy Staedter of Live Science in 2017.

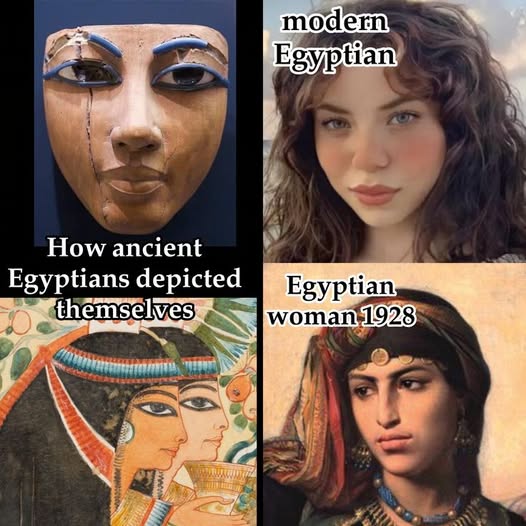

The images released by Parabon show faces similar to modern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern individuals rather than modern Egyptians. Based on phenotyping, the team suggests that the mummies had light brown skin with dark hair and eyes.

According to the statement, Parabon’s 3-D facial reconstructions are “highly consistent” with the earlier genome analysis, which concluded that “ancient Egyptians shared more ancestry with Near Easterners than present-day Egyptians, who received additional sub-Saharan admixture in more recent times.”

In 2017, study co-author Johannes Krause, a paleogeneticist at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told the Washington Post’s Ben Guarino that the ᴀssessment showed “complete genetic continuity” across 1,300 years. In other words, though their kingdom was conquered by a succession of outside powers, the ancient Egyptians included in the analysis didn’t really intermix with invaders.

After predicting the three men’s likely phenotypes, the Parabon team searched the company’s database for people whose DNA closely aligned with the ancient Egyptians, reports Leslie Katz for CNET. Drawing on information pulled from the database, the researchers modeled the probable width, height and depth of the mummies’ heads and facial features. A forensic artist took over the process from there.

“It’s great to see how genome sequencing and advanced bioinformatics can be applied to ancient … samples,” says Parabon’s director of bioinformatics, Ellen Greytak, in the statement.

Speaking with CNET, Greytak adds, “This study was an exciting proof-of-concept of how much we can learn about ancient people from their DNA.”