Archaeologists in Eisleben, Germany, have uncovered the 1,000-year-old remains of an elite couple, adding a layer of mystery due to the missing facial bones of the woman.

The graves, found near the former royal palace of Helfta, have sparked intrigue and speculation about the circumstances surrounding this enigmatic burial.

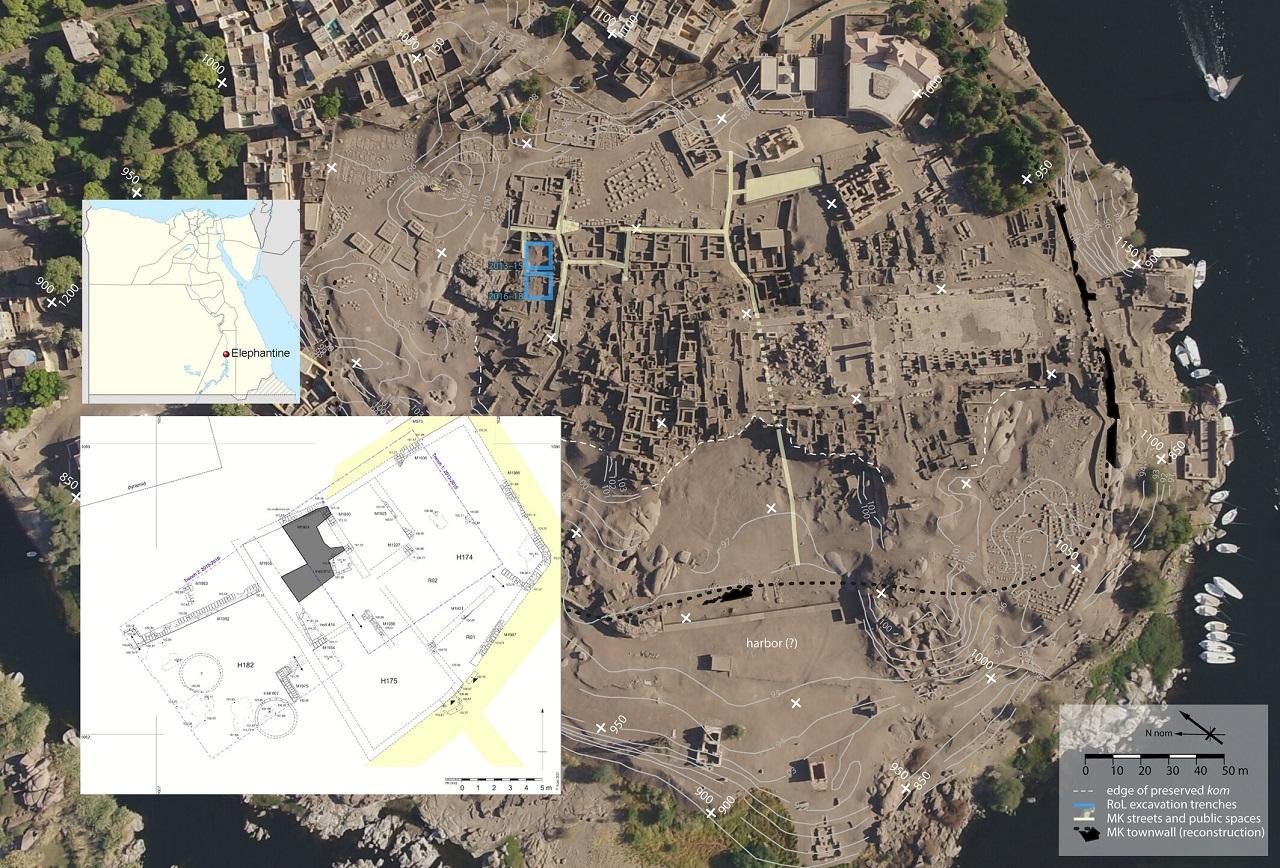

The peтιтe woman, approximately 1.55 meters tall, and her slightly taller husband are believed to have lived in the 9th century, during the Carolingian period. The royal palace, a residence for emperors Otto the Great and Otto II, served as the backdrop for this extraordinary find. The burial site, untouched by disturbances, presents an unusual aspect—the woman’s facial bones are entirely absent.

While the cause of the missing bones remains a mystery, archaeologists are exploring various theories. Felix Biermann, an archaeologist from the Saxony-Anhalt State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology, noted that the woman’s intentional burial without common grave goods, such as jewelry, could indicate a departure from traditional practices. This divergence hints at a possible embrace of more modern or Christian beliefs, suggesting a unique mindset compared to her husband.

“The fact that there was nothing with her is very unusual. Maybe she was already Christian, but the man was even more traditional. In Christianity, these kinds of additions were avoided,” explained Biermann.

The archaeological team discovered a knife, a belt set, and official staff fittings, resembling those carried by generals, with the husband. This collection suggests the man held a higher social rank, possibly managing a castle. As archaeologists delve into this 1,000-year-old cold case, the woman’s missing facial bones pose a central puzzle.

The vicinity of the couple’s graves to the medieval castle and the impressive artifacts buried with the man indicate wealth and high social status. The woman’s conscious decision to forgo grave goods and her distinctive burial set her apart from the conventional practices of her time.

The broader archaeological site in Eisleben has unveiled not only this unique burial but also extensive ruins, including castle fortifications, pit houses, and a royal structure built over the original palace in the 12th century. The complex gives information about the dense settlement and infrastructure of the imperial palace during the Carolingian-Ottonian period (750-1024 CE).

Excavations in 2021 uncovered a medieval church foundation attributed to Otto I, highlighting the site’s historical and religious significance. As the archaeological team meticulously examines the remains of the elite couple in a laboratory, questions about the circumstances of their deaths and the absence of facial bones persist.