How Ancient Egyptian Cosmetics Influenced Our Beauty Rituals

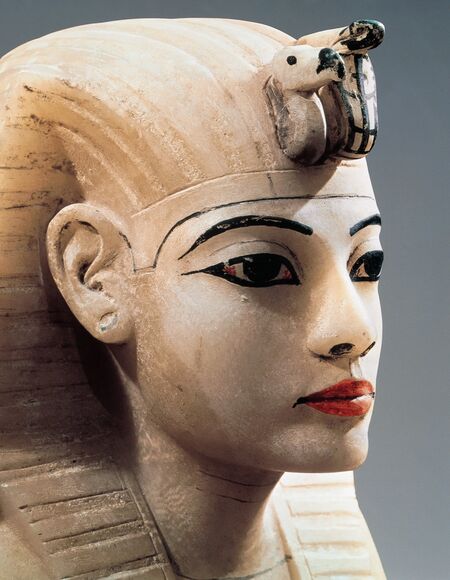

Ancient Egyptian painted alabaster head from Treasure of Tutankhamen, New Kingdom, XVIII Dynasty. PH๏τo By DEA / G. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini/Getty Images.

Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963). PH๏τo Universal History Archive / Contributor.

The mysteries of the ancient Egyptians are vast, but their beauty tricks are no secret. Makeup might seem like a modern phenomenon—one that has grown into a trillion-dollar business—but cosmetics were equally important to daily life in the ancient world. From the earliest era of the Egyptian empire (around 6000 B.C.E.), men and women from all social classes liberally applied eyeliner, eyeshadow, lipstick, and rouge.

The perceived seductiveness of Egyptian civilization has a lot to do with how we’ve glamorized its two most famous queens: Cleopatra and Neferтιтi. In 1963, Elizabeth Taylor defined the chic Egyptian look when she portrayed Cleopatra in the eponymous epic. In 2017, Rihanna (herself a makeup magnate) perfected it when she paid tribute to Neferтιтi on the cover of Vogue Arabia. In their homages, both beauty icons wore saturated blue eyeshadow and thick, dark eyeliner.

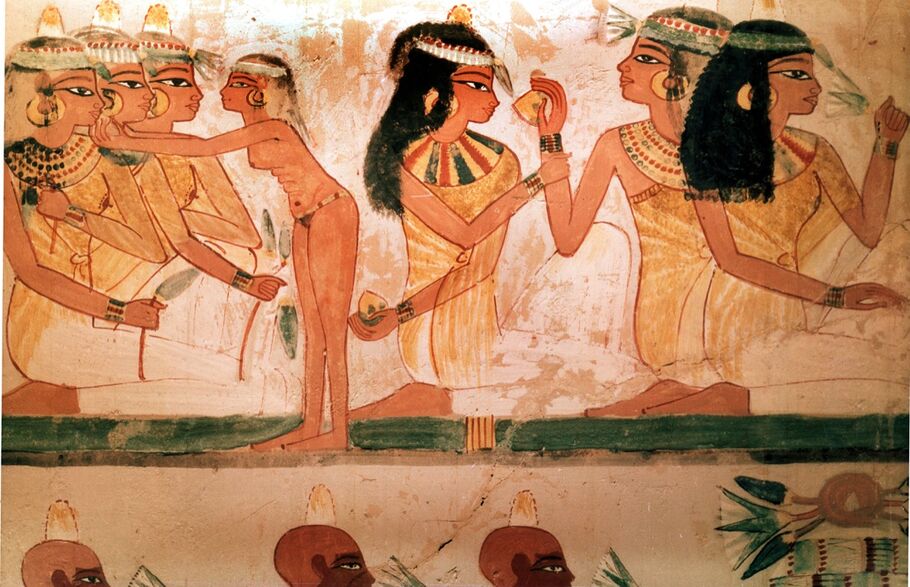

A detail of a painting from the tomb of Nakht depicting three ladies at a feast. They wear perfumed cones in their hair and elaborate necklaces. Egypt, 18th dynasty, ca. 1421–1413 B.C.E. Tomb no. 52, West Thebes. (PH๏τo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images).

Yet ancient Egyptians didn’t only apply makeup to enhance their appearances—cosmetics also had practical uses, ritual functions, or symbolic meanings. Still, they took their beauty routines seriously: The hieroglyphic term for makeup artist derives from the root “sesh,” which translates to write or engrave, suggesting that a lot of skill was required to apply kohl or lipstick (as anyone who has tried to emulate beauty tutorials on YouTube can attest).

The most refined beauty rituals were carried out at the toilettes of wealthy Egyptian women. A typical regimen for such a woman living during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1650 B.C.E.) would have been indulgent, indeed. Before applying any makeup, she would first prepare her skin. She might exfoliate with ᴅᴇᴀᴅ Sea salts or luxuriate in a milk bath; milk-and-honey face masks were popular treatments. She could apply incense pellets to her underarms as deodorant, and floral- or spice-infused oils to soften her skin.Egyptians also invented a natural method of waxing with a mixture of honey and sugar. “Sugaring,” as it’s called today, has been revived by beauty companies as a less painful alternative to H๏τ wax.

After all this, a servant would bring in the many ingredients and tools necessary to create and apply her makeup. These apparatuses, containers, and applicators were themselves lavish art objects that communicated social status. Calcite jars held makeup or unguents and perfumes; containers for eye paint and oils were crafted from expensive materials like glᴀss, gold, or semi-precious stones; and siltstone palettes used to crush materials for kohl and eyeshadow were carved to resemble animals, goddesses, or young women. These symbols represented rebirth and regeneration, and the act of grinding pigments on an animal palette was thought to grant the wearer special capabilities by overcoming the creature’s power. (Members of the lower classes used more modest tools when applying their own makeup.)

The servant would create eyeshadow by mixing powdered malachite with animal fat or vegetable oils. While the lady sat at her toilette, before a polished bronze “mirror,” the servant would use a long ivory stick—perhaps carved with an image of the goddess Hathor—to sweep on the rich green pigment. Just as women do today, eyeshadow would be followed with a thick line of black kohl around her eyes.

Mirror with a Handle in the Shape of a Young Woman, ca. 1550–1391 B.C.E. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Combs with Carved Animals, ca. 3900–3500 B.C.E. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This part of the routine had practical purposes beyond beautifying the wearer. Kohl was used by both Sєxes and all social classes to protect the eyes from the intense glare of the desert sun. The Egyptian word for “makeup palette” derives from their word meaning “to protect,” a reference to its defensive abilities against the harsh sunlight or the Evil Eye. Additionally, the toxic, lead-based mineral that it was made from had antibacterial properties when combined with moisture from the eyes.

The final touches to this lady’s makeup would, of course, be red lipstick—a classic look even today. To make the paint, ochre was typically blended with animal fat or vegetable oil, though Cleopatra was known to crush beetles for her perfect shade of red. These highly toxic concoctions, often mixed with dyes extracted from iodine and bromine mannite, could lead to serious illness, or sometimes death—possibly where the phrase “kiss of death” derives from.

Tweezer-Razor, ca. 1560–1479 B.C.E. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In death, too, personal appearance was crucial to Egyptian idenтιтy. Burial sites uncovered from the very beginning of the society’s history, in Predynastic times, show that it was common for Egyptians to include everyday items like combs, scented ointments, jewelry, and cosmetics (many examples found with makeup still inside them) in the graves of men, women, and children.

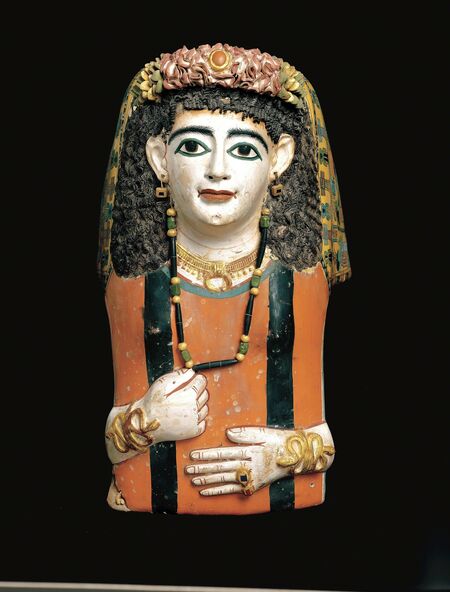

We might closely ᴀssociate the Egyptians with their dramatic beauty looks largely because of their prolific use on mummies and death masks. Instead of depicting their subjects’ real features, these cartonnage masks and wooden coffins portray idealized youths with smooth skin and kohl-rimmed eyes. In fact, mummification itself followed many of the daily self-care rituals Egyptians followed while alive. Unguents for softening the skin took on religious significance when they were used to anoint the body, and even cosmetics were sometimes applied.

Cosmetic Dish in the Shape of a Trussed Duck, ca. 1353–1327 B.C.E. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.