A recently published study, released in Royal Society Open Science, has turned a new and surprising chapter in medieval manuscript history: dozens of volumes long believed to be bound in local animal hides were actually covered with seal skin shipped from the cold northern waters of the Atlantic.

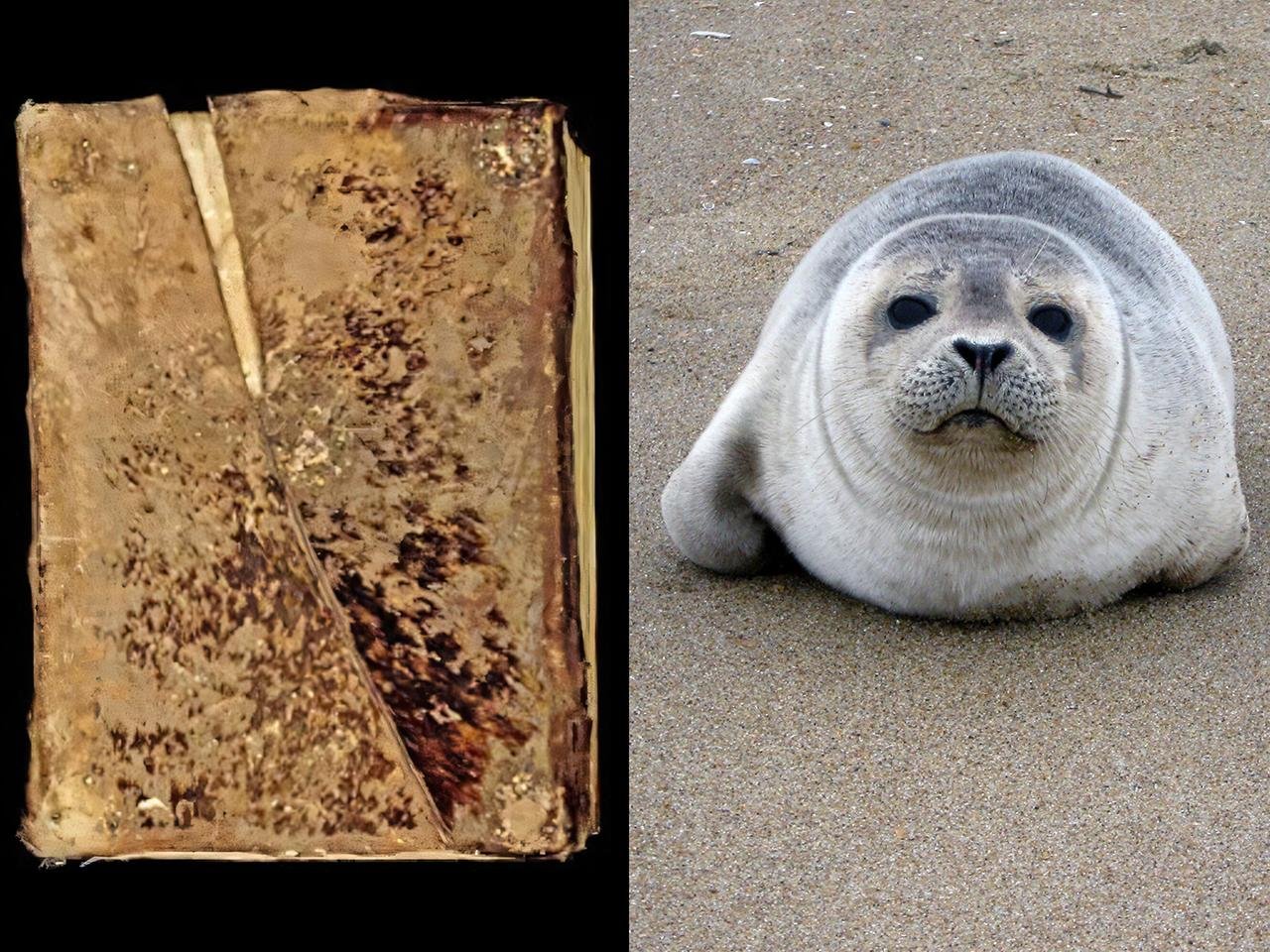

(Left) Romanesque binding from Clairvaux covered with a hair-covered chemise (Médiathèque du Grand Troyes, ms. 35, ca. 1141–1200), sample EL53. (Right) A harbor seal. Credit: (Left) E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025); (Right) USFWS/Pixabay (CC0)

(Left) Romanesque binding from Clairvaux covered with a hair-covered chemise (Médiathèque du Grand Troyes, ms. 35, ca. 1141–1200), sample EL53. (Right) A harbor seal. Credit: (Left) E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025); (Right) USFWS/Pixabay (CC0)

The collaboration between an international team of archaeologists, historians, and bioinformatics experts compared 32 French, English, and Belgian Cistercian monasteries’ books, particularly those from the renowned Clairvaux Abbey in France’s Champagne province. Using advanced scientific techniques like electrostatic zooarchaeology by mᴀss spectrometry (eZooMS) and ancient DNA analysis, the scientists discovered that some of the so-called “hairy books” — named as such due to the visible hair fibers on their outer coverings, or chemises — were bound with the skin of seals.

The use of sealskin on manuscript covers was not completely unknown in Scandinavia and Ireland. However, its widespread presence in interior French monasteries took researchers aback.

The majority of medieval texts were written on parchment made from the skin of land animals like calves or sheep. Their covers, traditionally ᴀssumed to be of local material like boar or deer, were believed to reflect regional availability. But this new study reveals that the chemises enveloping many 12th- and 13th-century books were actually made from seals — specifically harbor seals, harp seals, and bearded seals. They even traced their geographical origin to places as far as Scandinavia, Denmark, Scotland, Iceland, and Greenland.

A primary hair, flat at the base. Ms 31 (Médiathèque du Grand Troyes). Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

A primary hair, flat at the base. Ms 31 (Médiathèque du Grand Troyes). Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

This discovery has shifted the history of medieval trade. All of the sealskin-bound books, say researchers, came from abbeys in places along medieval trading corridors, like Norse trade routes that extended deep into continental Europe. The routes not only transported goods like walrus ivory and fur but possibly sealskin, perhaps traded by the descendants of the Vikings.

Interestingly, the Cistercian monks using these sealskin bindings may not have even been aware of what kind of animal they were using. Seals were not typically depicted in medieval European artwork, and during this period, the French language had no term for “seal.” Furthermore, the procurement of sealskins is never noted in Clairvaux Abbey documents. This is proof that the skins arrived indirectly via extensive trade networks.

Bearded seal (Wikicommons (a); harbour seal in Greenland, © Morten Tange Olsen (b); young harp seal skin, © Morten Tange Olsen (c)). Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

Bearded seal (Wikicommons (a); harbour seal in Greenland, © Morten Tange Olsen (b); young harp seal skin, © Morten Tange Olsen (c)). Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

While sealskin was most likely chosen because it is so durable and resistant to water, aesthetics may also have played a role. The Cistercian order, which broke off from the Benedictines in 1098, favored white or light-colored textiles as opposed to the brown of the Benedictines. Although the sealskins are now browned with age, they likely were pale, silvery colors when first used — more to the Cistercians’ liking.

Macroscopic examination of a contemporary sample shows the light colour of the natural hair (this sample has been treated with artisanal, greasy techniques and is undyed). A few millimetres have been shaved from the lower end, exposing the dark appearance of the skin surface under the fur. Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

Macroscopic examination of a contemporary sample shows the light colour of the natural hair (this sample has been treated with artisanal, greasy techniques and is undyed). A few millimetres have been shaved from the lower end, exposing the dark appearance of the skin surface under the fur. Credit: E. Lévêque et al., Royal Society Open Science (2025)

The study ultimately challenges long-standing ᴀssumptions about medieval manuscript production. As the researchers wrote in their paper, “Contrary to the prevailing ᴀssumption that books were crafted from locally sourced materials, it appears that the Cistercians were deeply embedded in a global trading network.” The integration of biological sciences into historical research has not only uncovered the unexpected use of sealskin but also highlighted the monasteries’ connection to a far-reaching economic web that spanned from the Arctic to central Europe.

This study challenges conventional ᴀssumptions about medieval manuscript making. As the researchers wrote in their paper, “Contrary to the prevailing ᴀssumption that books were crafted from locally sourced materials, it appears that the Cistercians were deeply embedded in a global trading network.”

More information: Lévêque, É., Teasdale, M. D., Fiddyment, S., Bro-Jørgensen, M. H., Spindler, L., Macleod, R., … Collins, M. (2025). Hiding in plain sight: the biomolecular identification of pinniped use in medieval manuscripts. Royal Society Open Science, 12(4). doi:10.1098/rsos.241090