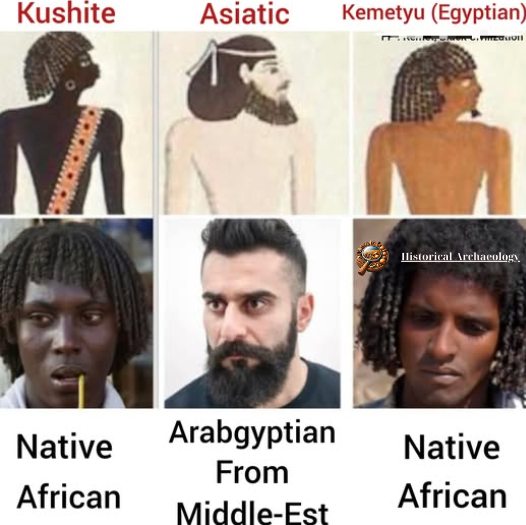

The ancient egyptians portrayed themselves and their neighbors with remarkable details and artistry. The first image depicts a Kusнιтe. As you can observe, Nilotic populations share a similar hairstyle tradition. In the middle, we see a Middle Eastern Arab, characterized by a full and well-groomed beard. The third image represents the Kemetyu (Egyptian). The twisted hairstyle, as shown in both the first and third images, continues to be a cultural practice among populations of the Nile Valley.

Egyptian Culture and Society

The unique environment of Egypt and the special benefits it conferred on its inhabitants were construed as divine gifts that made Egyptians superior to all other civilizations. For Egyptians, it was simply self-evident that their country—nurtured by the Nile and guarded by the deserts and seas that surrounded it—was the center of the universe.

RELIGION AND WORLDVIEW

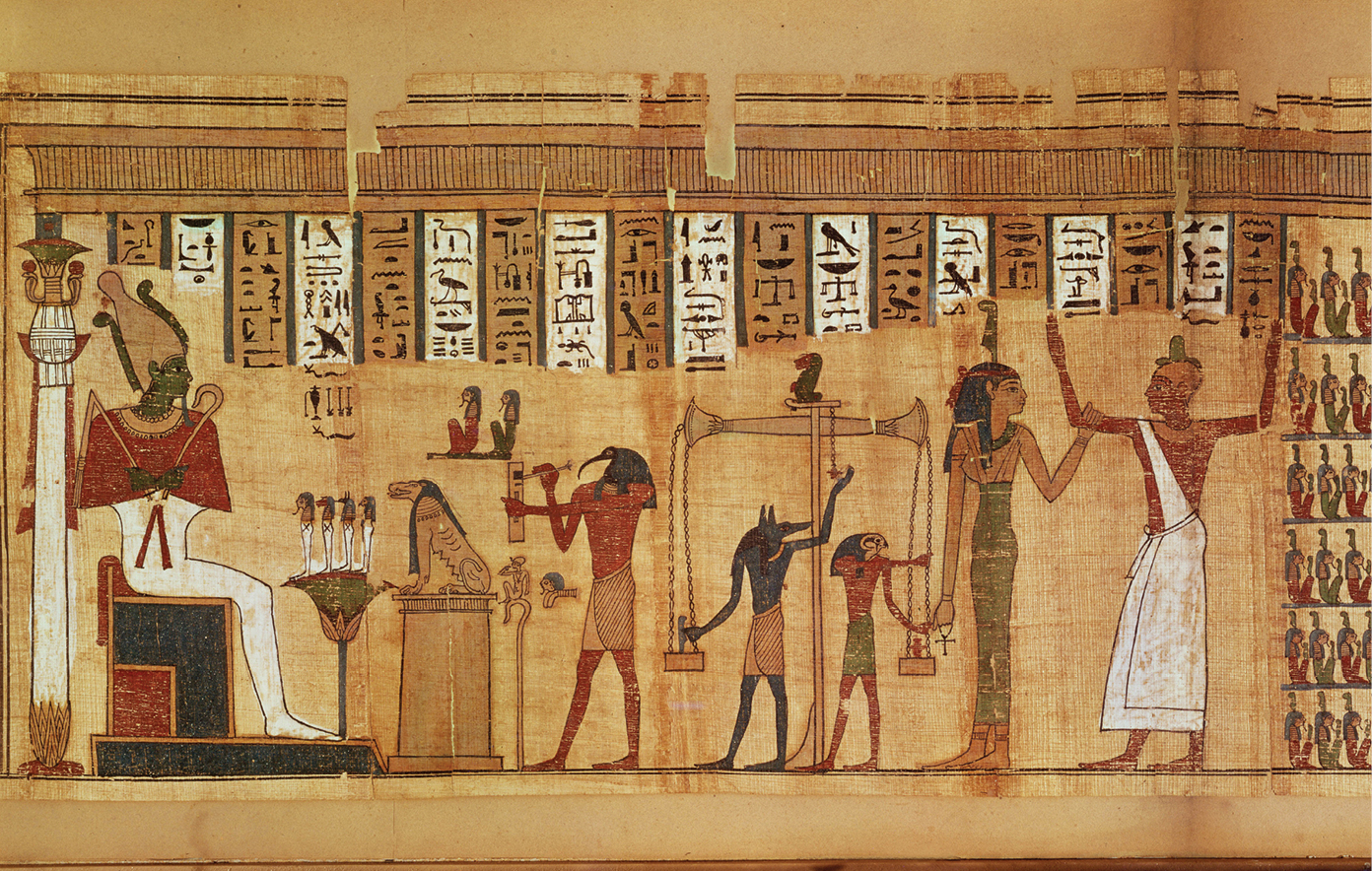

Unlike the peoples of Mesopotamia, who were constantly faced with new and terrible challenges—both environmental and political—the Egyptians experienced existence as predictably repeтιтive. This was mirrored in their perception of the cosmos. At the heart of Egyptian religion lay the myth of the gods Osiris and Isis, not only brother and sister but husband and wife. Osiris was, in a sense, the first pharaoh: the first god to hold kingship on earth. His brother Seth, however, wanted the throne for himself. So Seth betrayed and killed Osiris, sealing his body in a coffin. But their loyal sister Isis retrieved the corpse and managed to revive it long enough to conceive her brother’s child, the god Horus. Enraged by this, Seth seized Osiris’s body and hacked it to pieces, spreading the remains all over Egypt. Still undeterred, Isis sought the help of Anubis, the god of the afterlife. Together they reᴀssembled and preserved the scattered portions of Osiris’s body, thus inventing the practice of mummification. Then Horus, with the help of his mother, managed to defeat Seth.

Osiris was thereby avenged, and revived as god of the underworld. Like Egypt itself, he could not be killed; and the cycle of his death, dismemberment, and resurrection was reflected in the yearly renewal of life along the Nile.

LIFE AND DEATH IN ANCIENT EGYPT

In addition to embodying Egypt’s continual regeneration, Osiris exemplified the Egyptian atтιтude toward death, which was very different from the Sumerians’ rather bleak view. For the Egyptians, death was a rite of pᴀssage to be endured on the way to an afterlife that was more or less like earthly existence, only better. Yet the journey was full of dangers because the individual’s ka had to roam the Duat, the underworld, searching for the House of Judgment. There, Osiris and forty-two other judges would decide the ka’s fate. If successful and judged worthy, the deceased would enjoy immortality as an aspect of Osiris.

Egyptian funerary rites emulated the example set by Isis and Anubis, who had carefully preserved the parts of Osiris’s body and enabled his afterlife. This is why the Egyptians developed their sophisticated techniques of embalming, whereby many of the body’s organs were removed and treated with chemicals—except for the heart, which played a key role in the ka’s final judgment. A portrait mask was then placed on the mummy before burial, so that the deceased would be recognizable. To sustain the ka, food, clothing, utensils, weapons, and other items of vital importance would be placed in the grave along with the body.

“Coffin texts,” or books of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, also accompanied the body and were designed to speed the ka’s journey. They contained special instructions, including magic spells and incantations, which would help the ka travel through the underworld and prepare for the final test. They also described the “negative confession” the ka would make before the court of Osiris: a formal denial of offenses committed in life. The god Anubis would then weigh the deceased’s heart against the principle of ma’at: truth, order, justice. Because ma’at was envisioned as a goddess wearing a plumed headdress, a feather from this headdress would be placed in the scales, along with the heart, at the time of judgment; only if the heart was light (empty of wrongdoing) and in perfect balance with the feather would the ka achieve immortality.

Throughout the era of the Old Kingdom, the privilege of undergoing these preparations (and thus of ensuring immortality) was reserved for the royal family alone (see Analyzing Primary Sources on page 34). By the time of the Middle Kingdom, it was becoming possible for many Egyptians to ensure that their bodies would participate in these rituals, too. This manner of confronting death was inherently life-affirming, bolstered by confidence in the resilience of nature and the renewal of creation. Binding together the endless cycle was ma’at, the serene order of the universe with which the individual must remain in harmony, and against which each person’s ka would be weighed after death. Embodying ma’at on earth was the pharaoh. For most of the third millennium, thanks to a long period of successful harvests and peace, the Egyptians were able to maintain their belief in this perfectly ordered paradise and the pharaoh that ensured it. But when that order broke down, so did their confidence in the pharaoh’s power.

EGYPTIAN SCIENCE

Given the powerful impression conveyed by the pyramids, it may seem surprising that the ancient Egyptians lagged far behind the Mesopotamians in science, mathematics, and the development of new technologies. Only in the calculation of time did the Egyptians make notable advances. Their close observation of the sun led them to develop a solar calendar that was far more accurate than the Mesopotamian lunar calendar. Whereas the Sumerians invented our means of dividing and measuring the day, the Egyptian calendar is the direct ancestor of the calendar adopted for Rome by Julius Caesar in 45 B.C.E. (see Chapter 5) and later corrected by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 C.E. This is the calendar we use today. The Egyptians also devised some effective irrigation and water-control systems, but they did not adopt labor-saving devices like the wheel until much later, perhaps because the available pool of peasant manpower was virtually inexhaustible.