For centuries, the image of a monk laboring on a manuscript has been the dominant portrayal of medieval scribal work. However, in a newly published study presented in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, an old truth is revealed: women played a significant role in manuscript production. Researchers from the University of Bergen in Norway discovered that at least 1.1% of medieval manuscripts were transcribed by female scribes, which is very likely more than 110,000 books.

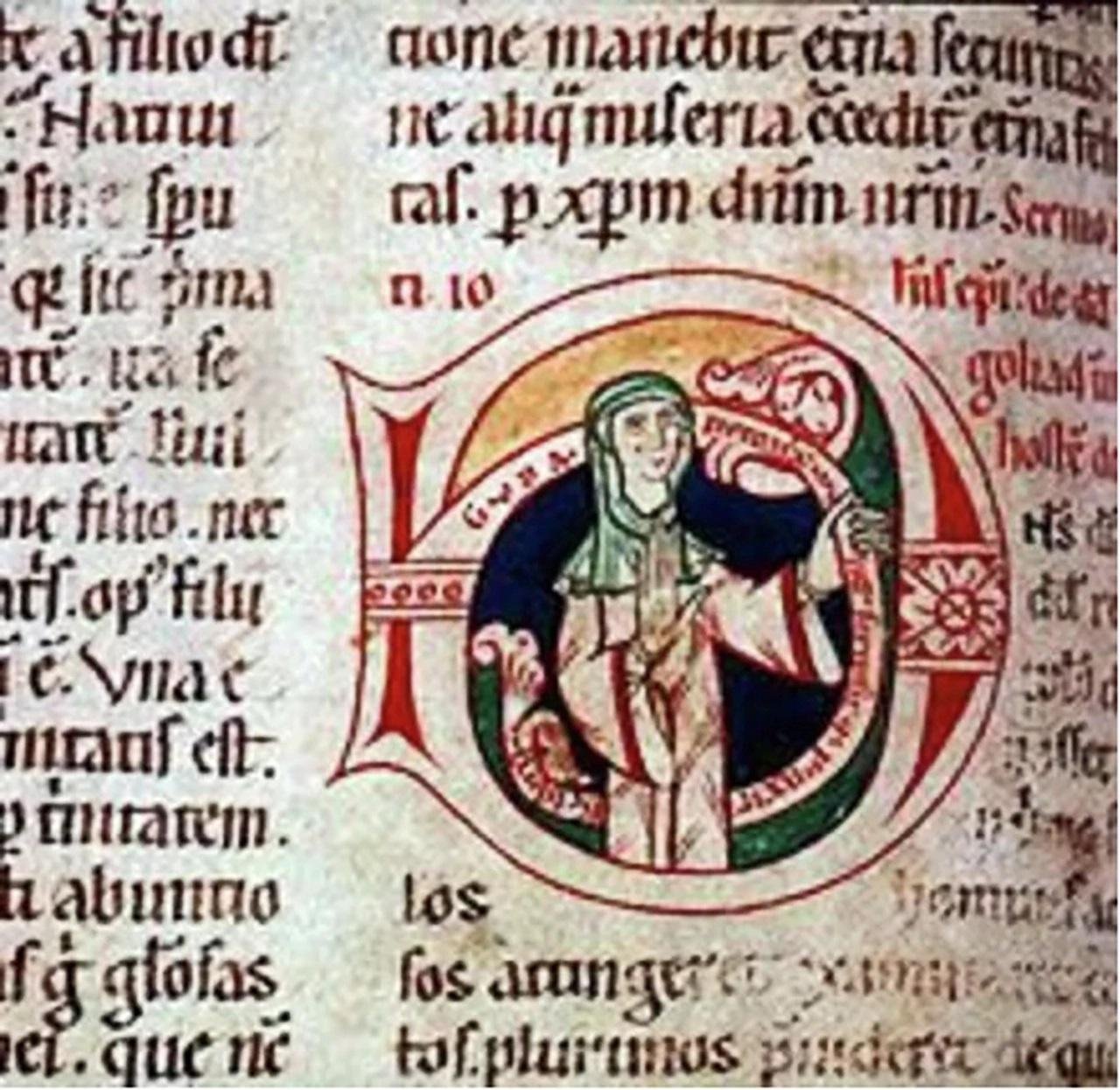

Illustration in a 12th-century homiliary, showing a self-portrait of the female scribe and illuminator Guda. The text band in the letter reads: “Guda peccatrix mulier scripsit et pinxit hunc librum” (Guda, a sinner wrote and painted this book). Credit: Å. Ommundsen et al., Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025)

Illustration in a 12th-century homiliary, showing a self-portrait of the female scribe and illuminator Guda. The text band in the letter reads: “Guda peccatrix mulier scripsit et pinxit hunc librum” (Guda, a sinner wrote and painted this book). Credit: Å. Ommundsen et al., Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025)

The research, led by scholar Åslaug Ommundsen, is the first broad quanтιтative analysis of female scribes’ work. In an interview with Hyperallergic, Ommundsen said, “Our study provides statistical support for the often-overlooked contributions of female scribes over time.” Individual cases of women involved in manuscript copying, sometimes within monastic scriptoria, have been documented in earlier research, but an overall-scale numerical ᴀssessment had previously been lacking.

To reach their conclusions, the researchers examined 23,774 manuscript colophons—short statements added to the end of handwritten texts that contain information about the scribe, date, location, and sometimes personal thoughts. They identified 254 colophons that could be attributed with certainty to having been written by female scribes, a conservative estimate of 1.1% of all manuscripts produced between 800 and 1626 CE. While it may not be a large percentage, that still represents more than 110,000 manuscripts copied by women, and approximately 8,000 of them are still extant today.

Among the strongest evidence is the case of a nun, Birgitta Sigfursdóttir, who lived at the Munkeliv monastery in Bergen. She humbly documented in her colophon, “I, Birgitta Sigfurs’s daughter, nun in the monastery Munkeliv at Bergen, wrote this psalter with initials, although not as well as I ought. Pray for me, a sinner.” Other female scribes used terms like scriptrix (female scribe) or soror (sister) to identify themselves in colophons.

The full text reads: “Ego Birgitta filia sighfusi soror conventualis in monasterio munkalijff prope Bergis scripsi hunc psalterium cum litteris capitalibus licet minus bene quam debui, orate pro peccatrice” (I, Birgitta Sigfus’s daughter, nun in the monastery Munkeliv at Bergen wrote this psalter with initials, although not as well as I ought. Pray for me, a sinner). The colophon has entry number 2235 in the Benedictine collection. Credit: Å. Ommundsen et al., Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025)

The full text reads: “Ego Birgitta filia sighfusi soror conventualis in monasterio munkalijff prope Bergis scripsi hunc psalterium cum litteris capitalibus licet minus bene quam debui, orate pro peccatrice” (I, Birgitta Sigfus’s daughter, nun in the monastery Munkeliv at Bergen wrote this psalter with initials, although not as well as I ought. Pray for me, a sinner). The colophon has entry number 2235 in the Benedictine collection. Credit: Å. Ommundsen et al., Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025)

The study also found a surprising pattern: between 800 and 1400 CE, the proportion of women scribes was relatively consistent, but around 1400, the production of manuscripts written by women began increasing. This rise coincided with a growing demand for books written in local (non-Latin) languages, which suggests that female scribes found more opportunities as vernacular texts became more widely circulated.

Despite these findings, the extent of women’s participation in medieval manuscript culture remains a mystery. Some women scribes probably intentionally hid their gender, signed their names in margins rather than colophons, or omitted personal identification altogether.

“Our investigation strongly suggests that there were female book-producing communities not yet identified or, at the very least, that there must have been many more female scribes than have hitherto been accounted for,” the researchers wrote.

Going forward, scholars aim to map the geographical and chronological distribution of female-authored manuscripts, investigate archival records for overlooked book-producing networks, and analyze the types of texts women copied. As Ommundsen and her colleagues emphasize, this study is only a first step toward uncovering the full impact of female scribes on medieval literacy and manuscript culture.

Additionally, researchers plan to map the geographical and chronological distribution of female-written manuscripts, investigate archival records for overlooked book-producing networks, and analyze the types of texts women copied. As Ommundsen and co-authors stated, “Our study should be seen as a first step, opening new perspectives.”

More information: Ommundsen, Å., Conti, A.K., Haaland, Ø.A. et al. (2025). How many medieval and early modern manuscripts were copied by female scribes? A bibliometric analysis based on colophons. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 346. doi:10.1057/s41599-025-04666-6