The tomb of Maiherpri

During his brief tenure as Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service (August 1897 – late 1899), Victor Loret spent most of his time conducting excavations. The highlight of this was undoubtedly his work in the Valley of the Kings where, in a little over a year, he discovered six new tombs, including those of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs – Thutmose III (KV34); AmenH๏τep II (KV35, which included the second cache of royal mummies); and Thutmose I (KV38) – thereby proving that the main valley was not just a cemetery of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasty ‘Ramesside’ pharaohs.

Tomb Discovery

Excavations to the south of the tomb of AmenH๏τep II (KV35), and near the main axis of the Kings’ Valley, led to the discovery of a small undecorated shaft tomb (KV36). On March 30th 1899, Loret was able to descend the vertical shaft, look into the single cham-ber at the bottom, and so become the first to discover a substantially intact burial in the Valley of the Kings – that of Maiherpri. Virtually the whole of the floor area of the chamber was filled with artefacts – clearly disturbed, but relatively intact.

Unfortunately, Loret (who was a very diligent excavator and record-keeper) was soon driven to resign from the Directorship and left for France to pursue a career in lecturing, leaving the tombs of both Maiherpri and Thutmose I unpublished. Until recently, the location of objects within Maiherpri’s burial chamber could only be vaguely hazarded from brief comments in the museum catalogue prepared by Georges Daressy, and from some general points written ‘for popular consumption’ (published in the journal Sphinx) by the German explorer and botanist Georg Schweinfurth, who had visited the tomb during the clearance of objects. He mentioned that a lidless coffin lay “inverted in the middle of the chamber”, but sadly only gave the location of most items in relation to a large box sarcophagus – the position of which was never stated! He said that a gaming board and related pieces were found “between the sarcophagus and the wall of the chamber”, with boxed provisions and garlands “in the northern corner behind”; and that thirteen large storage jars containing refuse embalming materials were “on the wall opposite the sarcophagus”. Other clues were nothing more than fuel for the imagination: “… strange weapons and works of art have been brought to light in the burial chamber …”.

Documenting the Tomb

This was the position which confronted Egyptologists until 2004, when Patrizia Piacentini of the University of Milan discovered Loret’s notebooks in the Archives of the Insтιтut de France – at the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris. These sketches were published in La Valle Dei Re Riscoperta (2004). Among the discoveries were Loret’s annotated sketch-plans, carefully recording the location of items within Maiherpri’s tomb and occupying pages 13-30 of his Carnet (notebook) II. From these notes it is clear that he started by recording the layout of objects visible when the tomb was first entered on March 30th 1899, and then made addi-tional notes as items were cleared to reveal others concealed beneath and behind them.

Loret’s initial rough sketch plan shows that the vertical tomb-shaft opened into the centre of the east wall of an approximately square chamber; with a fan of rubble extending from the doorway for over a metre in all directions. Filling most of the space to the right was a large box sarcophagus, painted black with gilded decoration, the head-end close to the far wall. In the corner before this stood a wooden canopic chest, and nearby lay a papyrus roll and a number of fragments comprising Maiherpri’s Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. Wooden boxes (‘coffinettes’) of mummified meat lay closer to the doorway. Directly ahead were the base and lid of an unfinished gilded anthropoid coffin, both inverted and laid with the head-end towards the far wall. Propped against the left-hand wall and resting on a double row of large storage jars was an ‘Osiris bed’, shaped in the profile of the mummified god and planted with barley to sprout after the burial. A quiver was propped against the coffin base, resting upon two alabaster vases lying nearer the door-way.

This and subsequent sketches were roughly drawn to show the broad relationship of one item to another, with-out any great precision with regard to measurements. For instance, although on the sketch plan there appeared to be a broad space between the sarcophagus and the adjacent walls, the items noted by Loret between the sarcoph-agus and the right-hand/north wall – including some relatively coarse cloth, a pair of pottery vases, a marquetry box with checker inlays – would not have taken up much room. In the open space between the head-end of the sar-cophagus and the far/west wall he wrote “rein” (nothing). He made smaller sketches to show the detail of finds within a specific area, for instance small pottery items lying beyond the inverted coffin lid and base, and archery equipment in the near left-hand corner: a gilded leather arm-guard, a wrist-guard, and a number of arrows propped on a second quiver and leaning against the wall. Nearer the entrance was an attractive bowl in blue ‘porcelain’ with designs of fish, animals and plants both inside and out.

During their rummaging the ancient plunderers had scattered items, covered one with another, and also smashed a great deal. As he had done in the tombs of Thutmose III (KV34) and AmenH๏τep II (KV35), Loret diligently recorded the location and condition of each piece. The north-eastern ‘Corner of the Canopics’, as Loret described it, received close attention. The outer lid of the canopic box was propped against the north wall nearby. Within the box:

“The canopic [jars] were swaddled with the face and inscription uncovered; and with linen pads between them and the wooden [box] walls to prevent rubbing. The box is open and two of the pads thrown on or beneath items 49 – 57”.

Later, Loret also marked the position of the inner lid, leaning against the east wall. Items 49 – 57 were the previously-mentioned boxes of mummified meat, which he now also carefully mapped.

The remaining area of the tomb chamber examined was that along the south wall to the left of the upturned coffin lid. Alongside the wall, occupying approximately half the length, were two rows of five large storage jars – indicated in whole or part on five of Loret’s sketch plans. These ten jars remained stoppered and sealed, having been left undisturbed by the robbers who presumably appreciated that they simply contained the swabs and left-over mummification materials comprising Maiherpri’s embalming cache. The Osiris bed, tossed against the wall, rested on the five outer jars.

Mapping the Tomb

By April 1st 1899, it was possible to take measurements and draw up a plan and section of KV36, the accu-racy of which may be confirmed with reference to the results obtained by the Theban Mapping Project. This would also appear to be the point at which Loret noted the dimensions of the large outer sarcophagus, and its distance from the near and right-hand side walls. The length of the sarcophagus and the distance from the east wall, 2.85 + 0.85 = 3.68m, deducted from the length of the chamber, 3.90, left just 0.20m (approximately 8 inches), and indicates why Loret wrote “rien” in the space at the far (west) end. This shows very clearly that the ten large jars shown occupying this area on the large fold-out plan in La Valle Dei Re Riscoperta must have been located elsewhere. Indeed, they are simply a duplication of the embalming cache located beneath the Osiris bed, based on a misreading of one of Loret’s sketches.

Much of the confusion and disorder evident among the tomb contents was clearly the result of pilfering by robbers in antiquity, who had naturally focused on what were the most valuable and easily-traded goods at that time. Missing were items which would have been anticipated in a high-status burial, such as metal vessels, unbroken glᴀss vases, or boxes of clothes and linen. Pottery jars of valuable moringa oil were not taken, however, probably because it had gone stale. The robbery had evidently been fairly rushed because within the large box-sarcophagus, a black-painted anthropoid coffin still retained gilded inscribed bands and panels, and within this the inner coffin was still covered in thin gold foil. As Daressy noted, this inner coffin had been forced open, and the bandages of Maiherpri’s mummy slashed to remove most of his jewellery – including his earrings, and most of his golden sandals. However, the golden leaf-shaped plate still remained covering the embalming incision in his lower left flank, and he retained his fine gilded cartonnage funerary mask. The upturned coffin lying in the middle of the chamber had, however, been left there by the original burial party, owing to the fact that it did not quite fit within the one found housing the mummy.

Who Was Maiherpri?

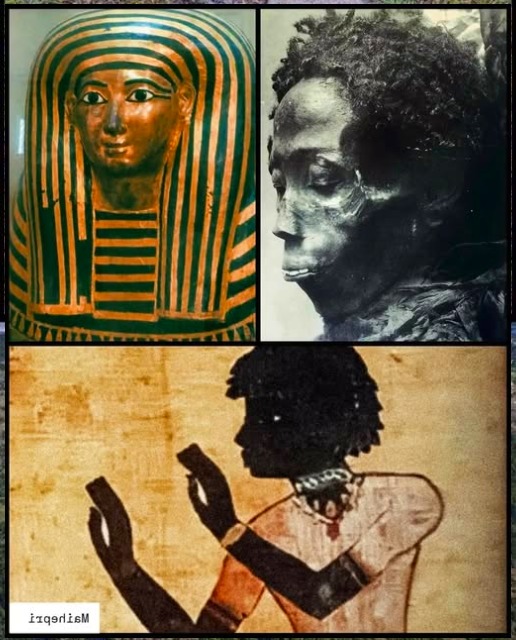

The clearance of the tomb was completed on April 2nd, and the entire funerary ᴀssemblage packed-up ready for shipment to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo on April 7th. There, the items were eventually catalogued by the museum curator, Georges Daressy, who confirmed that the burial was that of a courtier: ‘fanbearer on the right hand of the king’, and ‘child of the kap’, Maiherpri, whose Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ papyrus showed him as a dark-skinned young man with black, curly hair. When Daressy unwrapped the mummy (on March 22nd 1901) he found it to be a man of about 24 years, probably of Nubian descent, with dark skin and black, curly hair , corroborating the image on the funerary papyrus. The matching hair on the mummy turned out to be a wig, however, and the facial features were characteristic of the Eighteenth Dynasty royal house, which led some commentators to question Maiherpri’s ethnicity. However, the тιтle ‘child of the kap’ suggests that he was raised and educated in the palace nursery, and was perhaps a king’s son born to a Nubian princess/queen.

In this environment he may have become a close-com-panion to a half-brother, the eventual successor to the throne. His тιтle of ‘fan-bearer on the right-hand of the king’ is that of an especially favoured courtier. He might have acted as a personal bodyguard in battle, and his name – Maiherpri, “The Lion of the Battlefield” – might be the reality behind Ramesses II’s depiction (as at Abu Simbel) of a lion accompanying his chariot. The quanтιтy of archery equipment in the tomb – including two quiv-ers, a large number of arrows, and two arm-guards – would seem to allude to warfare, in which the Egyptians continuously emphasised the importance of archers. However, the presence also of two dog collars – one nam-ing the dog, Tantanuet – might also suggest that Maiherpri sometimes served as the king’s ‘master of the hunt’.

In February 1902, a team working for Howard Carter (on behalf of the American millionaire, Theodore Davis) discovered a yellow wooden box giving the name and тιтles of Maiherpri, buried in a hollow in the rock face above his tomb (KV36). Within were two sheets of very fine leather, carefully cut to form loincloths. The box might have been abandoned by robbers, who discov-ered that the contents were not what they’d hoped for.

Whose Reign?

One question remains: which king did Maiherpri serve? The pierced ears, the loincloths, and the тιтle ‘fanbearer on the king’s right hand’ all become commonplace in the reigns of AmenH๏τep II and Thutmose IV; and the papyrus is comparable to that of Kha from the reign of AmenH๏τep III. The burial cannot pre-date the reign of Hatshepsut whose prenomen (Maatkara) appears on one of Maiherpri’s linen wrappings. Clearly this linen could have been used after the death of the female king, but it is probably unlikely to have been considered acceptable following her persecution around the end of the reign of Thutmose III. In fact, all of the above-mentioned features can be shown to be consistent with a date in the reign of Thutmose III (especially if Nubian contexts are included), and Maiherpri’s funerary mask is of exactly the same style as that of Hatnofer, the mother of Hatshepsut’s minister, Senenmut. The tomb (KV36) is a little further from that of Thutmose III (KV34) than it is from that of AmenH๏τep II (KV35), though this latter is separated by a sharp ridge. In either case, the young ‘Lion’ was friend to a warrior pharaoh.

Dylan is a regular contributor to AE Magazine, with articles on Nefertari and Isetnofret (AE 126), and the so-called “Screaming Mummy” (AE 108). He has written for a wide of range of publications on the royal mummies and mummy-caches, and is the author of An Ancient Egyptian Case Book.