Excavating the archives of the man who uncovered Tutankhamun’s tomb

Marking the centenary of the greatest archaeological find in history, other “wonderful things” in the shape of documents, drawings and pH๏τographs are on display in Oxford’s Bodleian Library

It is rare to travel north in search of Tutankhamun. The young Pharaoh’s tomb is actually to the south, in Luxor, Egypt, as is his mummy, while the vast majority of artefacts buried with him – the famous “wonderful things” that include treasures such as the gold mask – have traditionally had their home at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. But there is another treasure linked to Tutankhamun, less glittering but also fascinating, in the shape of the archives of the late Howard Carter, the archaeologist who discovered the tomb.

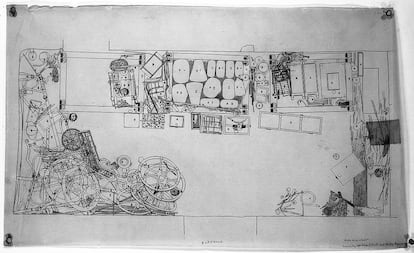

The documents compiled by Carter include maps and plans, detailed records of the thousands of artefacts – 5,300 to be exact, pH๏τographs, drawings, slides and both personal and excavation diaries, as well as other materials, such as private letters, telegrams and press clippings, all of which give the discovery context and are an exceptional source of information.

Donated to the center for Egyptology at Oxford University’s Griffith Insтιтute by Carter’s favorite niece and heir, Phyllis Walker who died in 1977, the collection is now the subject of a timely exhibition at Oxford’s Bodleian Library, with additional material from other sources such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Open until February 5, 2023, Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive, invites visitors to “see beyond” the golden treasures of the young Pharaoh and explore the complexity of the discovery as it unfolded. A celebratory centenary exhibition, it recalls the moment on November 26, 1922, when Carter and his sponsor Lord Carnarvon looked into the tomb for the first time, breaking a seal that had held for over 3,000 years and beginning the excavation of the only untouched ancient Egyptian royal burial site to be found in the Valley of the Kings.

The exhibition features Carter’s first written mention of the find in one of the Lett’s Indian and Colonial Rough Diary pocket notebooks he used to record his activities during the eight months he spent each year in Egypt: “First steps of tomb found,” he scrawled in pencil, conveying irrepressible enthusiasm. The entry takes up the entire page for Saturday, November 4, 1922. It was the fourth day into the last sponsored excavation, as Lord Carnarvon had finally decided to stop paying for the concessionary rights to the Valley of the Kings.

The exhibition goes into the details of the sensational find and how it developed for better and worse, with recognition of the fact that Carter and Carnarvon lied in order to smuggle several small objects out of Egypt. It also explains how the discovery coincided with the proclamation of Egypt’s independence from Britain and the change in the country’s policy regarding its antiquities; and it mentions the infamous “curse” ᴀssociated with the tomb. Significantly, it acknowledges the shortcomings of European colonial archaeology during that era and hails the essential role of the overlooked Egyptian professionals and laborers in the investigation.

The Egyptians, including many child laborers, appear in numerous pH๏τos of the excavation without being identified, reducing them to little more than exotic extras. They were rarely mentioned, and their role was underestimated in official reports. Now, archival research “is making it possible to restore the Egyptians’ role in the excavations,” and to “address the error.”

Donkeys instead of cabs

The exhibition also flags up the neglected role of the women who participated in the venture, such as Minnie, the wife of pH๏τographer Harry Burton, author of the famous pH๏τos of the excavation, who helped her husband and kept a personal diary that is a valuable source of information. In one pᴀssage, she recalls the excitement of visiting the tomb while it was being emptied and how Carter sent a donkey to fetch her home like someone might send a cab.

Coming to Oxford with the sole purpose of seeking out Tutankhamun lends the city an incongruous air of Egypt, even if arriving by bus rather than donkey. The kites spotted en route over the English countryside bring to mind the birds that fly over the pristine skies of Luxor, which are represented in pharaonic temples and tombs as divine creatures. These same birds are also present in Carter’s paintings, such as the 1895 watercolor of a falcon in the chapel of Anubis in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. Carter was an excellent draughtsman who came to archaeology precisely because of his artistic ability.

The Bodleian exhibition occupies the treasury room of the library and is small, like Tutankhamun’s tomb, but equally full of documentary wealth, though it requires immersion and the determination of an archaeologist to extract the information from the 20-odd showcases fittingly shrouded in gloom and mystery.

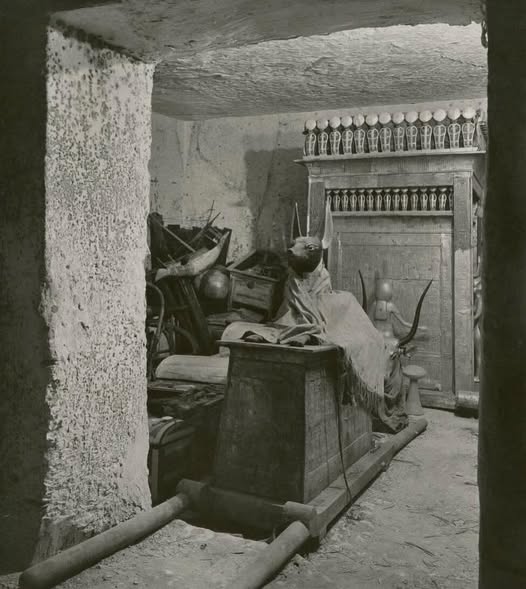

In a preamble, data is given on the reign of the young Pharaoh. For example, it is emphasized that his death was unexpected, and his burial consequently improvised, which explains many of its unusual characteristics. It is also mentions that the tomb remained substantially intact despite being visited by thieves shortly after first being sealed – they did not gain access to the mummy and the tomb was again rearranged and resealed so that what Carter encountered was virtually untouched. While it is written on a vaulting that the body of Tutankhamun is still in the sarcophagus, it was, in fact, removed from the stone coffin years ago and is exhibited in the same enclosure, but in a modern heated urn installed in the antechamber.

Obsession with the tomb

The tour begins with the climax of the discovery noted in Carter’s diary, before delving into the background of the discoverer himself, who was a complex personality who never married and had no children. A pH๏τo shows him at the age of 19, the same age as Tutankhamun when he died. An 1892 letter from the great Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who took him to Egypt, offers this insight: “His interest is in painting and natural history (…) He is of no use to me as an excavator.”

There is then a space dedicated to “the long search” – a period that began after a proclamation in 1913 by excavation sponsor Theodore Davis that the Valley is exhausted; enter Carnarvon, who hired Carter, as he was obsessed with the idea that there was still a tomb to be found. It is thrilling to actually see a map drawn by Carter’s own hand with the excavations between 1917 and 1922, when the tomb was not yet located, lying concealed beneath the remains of the ancient workers’ huts from the neighboring tomb of Ramses VI. And then, the great moment of the discovery and the first actual foray into the tomb, around four o’clock in the afternoon on November 26, by Carter, Carnarvon, his daughter and several others.

A page from Carter’s excavation diary contains the account of that Great Moment in his own handwriting. The hole in the door, the candle inserted, and Carnarvon asking: “Can you see anything?” The answer, Carter noted, was not the famous “yes, wonderful things” which he later claimed in subsequent records, but the less dramatic “yes, it’s wonderful.”

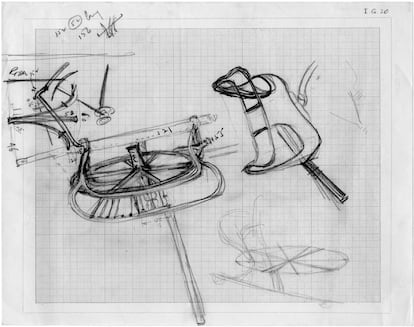

It was the beginning of an amazing scientific adventure that would last until December 1932, the 10 years it took to empty the tomb. Carnarvon died on April 5, 1923, without seeing the opening of the sarcophagus and the mummy of Tutankhamun, which was not examined until November 11, 1925. A letter from Carter to Egyptologist Alan Gardiner describes some of the emblematic artefacts observed in the antechamber: carts, beds with strange animal shapes, two life-size figures of guardians… “So far, it is Tutankhamun,” he writes.

Burton’s pH๏τos displayed in the exhibition are “the most famous archaeological images ever taken,” and these, together with the drawings of the different rooms of the tomb and the artefacts as they were discovered transport us to the key moments of the discovery. The exhibition also explains the conservation challenges faced by the archaeologists and the solutions they came up with to preserve the objects. Then there is documentation of the complex system of rails used to transport the tomb’s contents in wagons to the river to be shipped to the museum.

Particularly moving is a large portrait of an anonymous Egyptian boy pH๏τographed in 1927 by Burton wearing one of Tutankhamun’s necklaces, demonstrating how it would have been worn. Years later, Hussein Abd el Rasul, a member of the local Qurna family, identified himself as the sitter. The exhibition points out that “many stories have been told about the image and who the boy was and his role in the excavation.”

A group of Egyptian schoolchildren stopped in front of the pH๏τo the other day listening very attentively to the explanations of their teachers. Despite the lack of recognition for the Egyptians who worked on the tomb’s excavation, some names have nevertheless been salvaged thanks to the graтιтude Carter expressed in his writings, such as the name of the foreman, Ahmed Gerigar and his colleagues Gad Hᴀssan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.

Besides criticizing the patronizing atтιтude toward the Egyptians involved in the excavation, the exhibition flags up the pursuit of profit, especially Lord Carnarvon’s. It suggests that the origin of the famous curse on those tampering with the tomb mentioned in a delightful yellowed telegram in 1923 to “Carter Tutankhamun Thebes” from Dublin warning that if trouble continues he must reseal the tomb, was partly revenge by certain media angered by the aristocratic Carnarvon’s exclusive contract with The Times.

Curses and criticism aside, public excitement at the find was such during the 1920s that it inspired a boardgame and a rash of songs. Meanwhile, the archive, which continues to be enriched and has been digitized for open access (www.griffith.ox.ac.uk), is invaluable to the study of the tomb’s material, a work that Carter left unfinished.

For those whose appeтιтe for “wonderful things” is not yet sated, the Ashmolean Museum close by houses an extraordinary collection of Egyptian antiquities, such as the large statues of the god of fertility Min who appears excited at the sight of a sensual bust of Antinous, Hadrian’s lover who drowned in the Nile; an impressive stone head of a crocodile; the precious coffins and the mummy of the Theban priest Djed-djehuty-iuef-ankh and the Amarna pieces, which are closely linked to Tutankhamun as they represent his family, Akhenaten, Neferтιтi and the princesses, as well as to people and places he saw during his lifetime. The ostraca collection compiled by Gardiner, who collaborated with Carter, is also on display there.