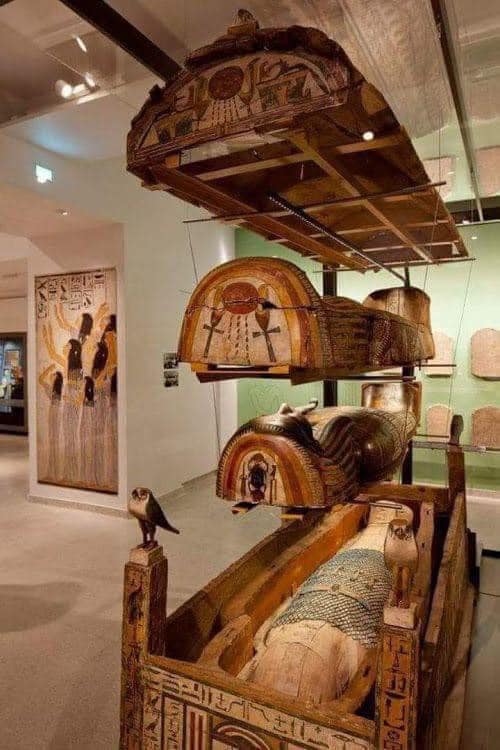

Inner coffin of Ankhshepenwepet

The Singer of the Residence of Amun, Ankhshepenwepet, was buried in a tomb within the precinct of Hatshepsut’s temple in Deir el-Bahri. The burial was plundered and no traces were left of her mummy, which would have been placed in the inner coffin.

The inner coffin of Ankhshepenwepet has a new shape which was developed during Dynasty 25. It is broader, with square shoulders and an over-sized head. On her head she wears a lappet wig (the hair painted blue), and a vulture headdress formerly worn by only queens and goddesses. The decoration on the lid includes the scene of the weighing of the heart from the Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, and below it, for the first time on coffins, the mummy is depicted. It lies on an embalmer’s bed and a ba-bird, symbolizing Ankhshepenwepet’s spirit, hovers above it (see detail pH๏τo). Beneath the bed are two groups of objects; four canopic jars and four viscera bundles (containing the internal organs). The fact that the bundles are depicted suggests that the jars are “dummy” canopic jars, like the ones in Ankhshepenwepet’s tomb (25.3.205a-d).