Uzbek Blue in Samarkand

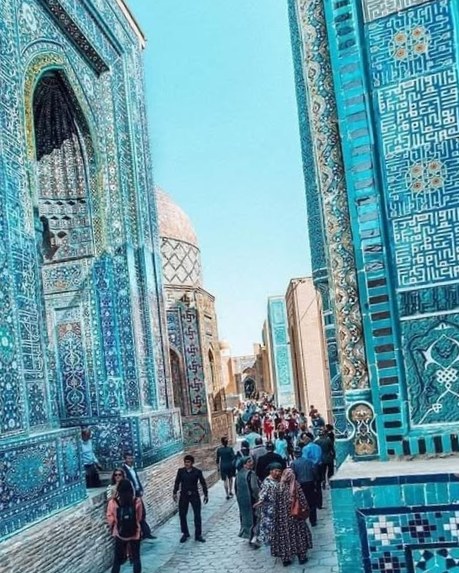

Almost every culturally important building in Uzbekistan is decorated with blue tiling, blue mosaics, blue glazing. Bright turquoise and teal, deep royal blue, light sky blue. There are other colors, sure, gold calligraphy, green vines, orange tigers, yellow stars, but if you squint your eyes and blur your vision, you’ll only see the blue.

I started calling the whole thing “Uzbek Blue” in my head. I like it because my eyes match it. 🙂

Why blue? I have a couple of explanations for you. Our guide said blue was the color of the nomads and their pagan religion. Blue is also the color of the sky, and what is more celestial and all-encompᴀssing than the heavens? God lives up there.

And I’m sure there was something about which minerals and stones were available. I also imagine that being able to build a mosque, madrasa, a mausoleum of blue was a sign of wealth, and wanting to show off is a universal human (male, especially) urge.

The best place to really be immersed in Uzbek Blue is in Samarkand, the most beautiful city in Uzbekistan. It’s not necessarily my favorite city (Tashkent is more livable in my opinion, as I sit here writing in a Tashkent coffee shop), but I think it’s definitely the most stunning.

I could spend my entire life learning about and explaining the history of Samarkand (and lots of people have), but I’m going to distill what I already know into three main points, so you don’t want to bash your head into your computer and I’m not sitting in this coffee shop until it closes.

Three things to remember about Samarkand:

1. It’s old. It was first settled in the 8th century BCE, although the buildings are obviously not that old.

2. Its history is extremely diverse. It’s been ruled by everybody from the ancient Sogdians to the Sᴀssanians to the Soviets. All the major conquerors have come through Samarkand: Alexander, Genghis Khan, Tamarlane. It’s also been visited and written about by history’s most important travelers, poets, and writers. Marco Polo called it a “noble city” and Ibn Battuta wrote that it was “one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty.”

3. It was the capital of the Timurid Empire, which was very big and wealthy (if relatively short-lived). Hence why there is now so much cool stuff in Samarkand—Tamarlane had to build stuff to show his vᴀssals how powerful and wealthy he was.

Today, although Samarkand is part of Uzbekistan, most of the population is ethnically Tajik and speaks Tajik. Tajikistan has historically been a little pissed that Samarkand belongs to Uzbekistan, but to be fair, Tajikistan was pretty busy with a civil war when the USSR dissolved.

I had a stomach bug in Samarkand, but thanks to an aggressive regimen of prescription anti-nausea medication and Advil, I made it to all the sights, and I’m glad I did. Most of the main tourist attractions in Samarkand are from the time of Amir Temur, aka Timur Tamerlane, aka Uzbekistan’s national hero. So we should talk about him for just a second. Hang in there with me.

Amir Temur conquered a swath of land that stretched from Istanbul to Delhi and founded the Timurid Empire. Like with Alexander, Temur’s empire was at its height during his lifetime, and then once he died, it slowly fell apart because none of his male descendants could really fill his shoes.

Temur is buried in a mausoleum in Samarkand with his two homicidal sons, his teacher, and his grandson, scientist and short-lived emperor Ulugh Beg. His bones were exhumed during Soviet times and we now know that his right knee didn’t bend (hence the name Tamarlane, which means somebody with a limp), and he was missing fingers on his right hand. Brilliant world leader with missing fingers…remind you of anyone else hehe?

Temur also built what was at the time the largest building in Central Asia, a mosque named after his first wife, Bibi Khanum (which is just a тιтle that means Mother/Lady/something like that). Temur married Bibi Khanum because she was a descendent of Genghis Khan, and it’s always good for a ruler to be able to say that he’s a part of Genghis Khan’s family. The legend goes that Temur was out on military campaign and his wife wanted the mosque to be finished by the time he returned, so she summoned the architect. The architect was in love with her and asked to kiss her on the cheek in exchange for finishing the mosque in time.

An argument ensued involving water, wine, and eggs (too long to explain here), but finally she relented and apparently the kiss left a mark on her cheek. What did he do—bite her? Anyway, Temur returned, saw the mark and summoned the architect, who knew that he was in deep sнιт. So instead of going to Temur, the architect built some wings, climbed to the top of the giant mosque, jumped off, and flew away. As one does.

A hundred years ago, both the mosque and the mausoleum were essentially ruins. They were painstakingly restored by the most unexpected of heroes: the Soviets. Who, according to our guide, did so mostly to encourage tourism.

The best thing that Temur built, in my opinion, was a collection of small mausoleums on a hill, a necropolis called Shah-i-Zinda. Shah-i-Zinda means “the living king.” Why is a that particular moniker used to refer to a hill for ᴅᴇᴀᴅ people? Because a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad had fled to the hill while trying to bring Islam to Samarkand—pagans weren’t happy about it and were chasing him. He jumped into a well and disappeared, but legend says that he is still alive and will return on Judgment Day. Hence, living. Today there’s a small mosque built on the site of the well. I was sitting inside the little mosque when the imam started singing and the Muslims in the room started to pray.

But the mausoleums on the hill are the best part. Unlike most other buildings like this in Uzbekistan, they didn’t need much Soviet restoration. Each was designed by a different Iranian master and is so small that the masters could afford to cover the entire façades with incredibly intricate designs. Even though the sun was beating down on my face, my stomach hurt, and I couldn’t get my headscarf to sit right, it was beautiful and I loved it.

I pᴀssed a thirty-something white dude and saw him gesture up to one of the mausoleums and say, “so, it’s another blue building, right?”

I couldn’t keep my mouth shut. “Not really,” I told him. “This one is eighty percent original, the Soviets didn’t have to do much to it. So the decorations are like five hundred years old, which is cool.”

Yeah, there are a lot of blue buildings in Uzbekistan, and they all start to blur together. But there’s nothing like them in the western world, and they represent centuries of culture and faith and wealth and tradition.

He was not sure what to say. I kept walking.