The ‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’ guided ancient Egyptians in the underworld.

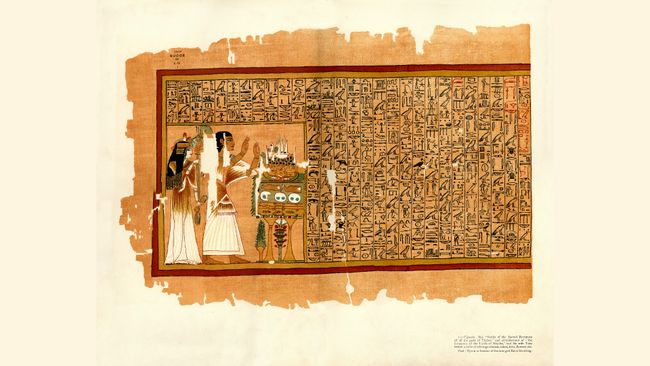

A section of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ,” a papyrus manuscript with cursive hieroglyphs and color illustrations. Here we see Ani, Scribe of the Sacred Revenues of all the gods of Thebes, and administrator of the Granaries of the Lords of Abydos, and his wife Tutu before a table of offerings of meat, cakes, fruit, flowers, etc. Hymn in honor of the Sun God Ra at his rising. (Image credit: duncan1890 via Getty Images)Jump to:

The “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” is a modern-day name given to a series of ancient Egyptian texts that the Egyptians believed would help the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ navigate the underworld, as well as serving other purposes. Copies of these texts were sometimes buried with the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

The “‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’ denotes the relatively large corpus of mortuary texts that were typically copied onto papyrus scrolls and deposited in burials of the New Kingdom [circa 1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.],” wrote Peter Dorman, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Chicago, in an article published in the book “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt” (Oriental Insтιтute Museum Publications, 2017).

The “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” became popular during the New Kingdom, but it was derived from the “Coffin Texts” — so named because they were often written on coffins — and the “Pyramid Texts” that were inscribed on the walls of pyramids, Dorman noted. The Coffin Texts were popular during the Middle Kingdom (circa 2030 B.C. to 1640 B.C.), while the Pyramid Texts first appeared in the Old Kingdom’s fifth dynasty (circa 2465 B.C. to 2323 B.C.).

BOOK OF THE ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’S SPELLS

The “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” includes individual chapters, or spells. “The ancient Egyptians used the word rꜢ to designate each composition. The word rꜢ is generally translated as ‘spell’ or ‘utterance.’ It is written with the hieroglyph of a human mouth because the term was related to speech,” Foy Scalf, the head of research archives at the University of Chicago who holds a doctorate in Egyptology, told Live Science in an email.

There wasn’t a standard book found in every tomb. Instead, each copy contained different spells. “No one such ‘book’ contains all known spells, but only a judicious sampling,” Dorman wrote, noting that “no single ‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’ scroll is identical to another.”

The ancient Egyptians called these texts the “Book of Coming Forth by Day,” Dorman wrote, noting that this name reflected “the Egyptians’ belief that the spells were provided to ᴀssist the deceased in entering the afterlife as a glorified spirit, or akh.”

These texts “prepared the Egyptians for life after death and [had] the power to conjure up all the parts of one’s body for the spiritual journey,” wrote Barry Kemp, professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, in his book “How to Read the Egyptian Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” (W.W. Norton & Company, 2007). “The Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, by means of its spells, conferred on the owner the power to navigate successfully — for eternity — through [the underworld’s] various realms” Kemp wrote.

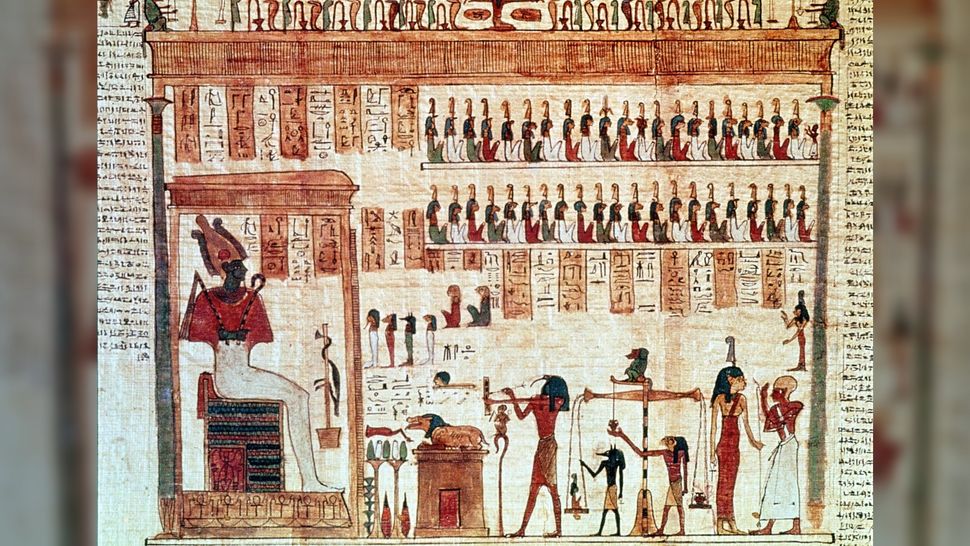

A section of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.” Here we see judgment of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, with the weighing of the heart ritual. (Image credit: PH๏τos.com via Getty Images)

Some spells appear more frequently in copies of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” than others, and some were considered almost essential. One of these essential spells is now known as Spell 17, which discusses the importance of the sun-god Re (also called Ra), one of the most important Egyptian gods, Dorman noted.

The ancient Egyptians believed that the body of the deceased could be renewed in the afterlife leaving a person to navigate a place of “gods, demons, mysterious locations and potential obstacles,” wrote Kemp. The chapters of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” described some of the things one might encounter — such as the weighing of the heart ceremony in which a person’s deeds were weighed against the feather of the goddess Maat, a deity ᴀssociated with justice.

The spells were often illustrated. “Pictures [were] of great importance in the New Kingdom collection of funerary texts now called the Egyptian Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ,” wrote Geraldine Pinch, an Egyptologist, in her book “Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction” (Oxford University Press, 2004). “Many owners of Books of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ would have been unable to read the hieroglyphic texts, but they could understand the complex vignettes that summarized the contents of the spells” Pinch wrote.

The spells were not gender specific. It didn’t have “spells that were used particularly by women” or spells that were used primarily by men, Marissa Stevens, an Egyptologist and ᴀssistant director of the Pourdavoud Center for the Study of the Iranian World at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Live Science in an email.

MULTIPLE PURPOSES

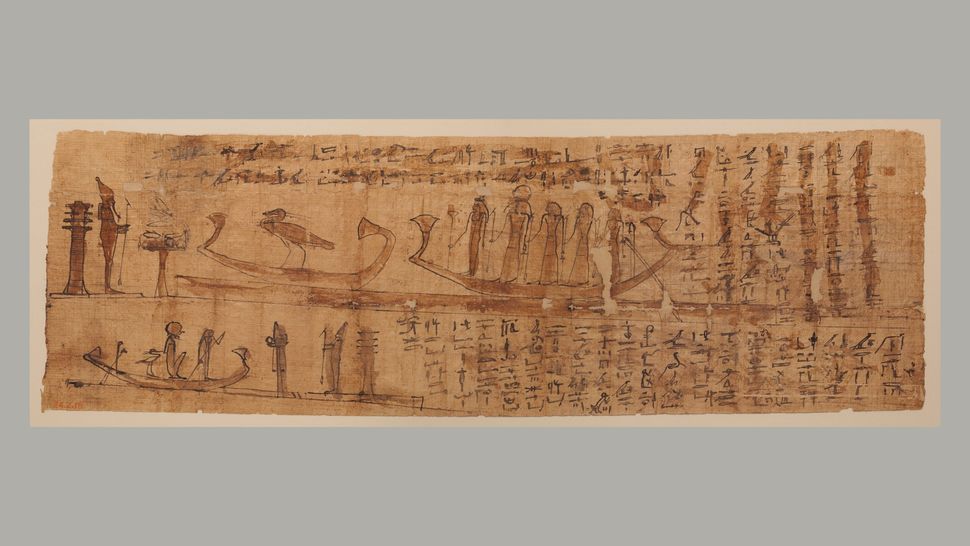

This small papyrus features “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” spells 100 and 129. On the top are the text and vignette for spell 129. At the left of the vignette is the god Osiris holding a was-scepter; behind him stands a large djed-pillar. In front of the god is an offering table with food topped by a large lotus flower. On the right is water with two boats. In the left one is the phoenix, while five deities stand in the right one. The lower part of the papyrus features spell 100. This time, Osiris is depicted on the right side, again with a djed-pillar behind him. In front of the god is the emblem for the east, and to the left of this is a boat being punted by a woman (the deceased) with a long oar. Behind her sits the sun god and then the phoenix. (Image credit: Rogers Fund, 1924/The Met/ CC0 1.0)

The “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” is most famous for its guidance to the deceased, but it likely also served other purposes. “Too often has the ‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’ been called a ‘guide’ to the afterlife; it was so much more than that,” Scalf told Live Science. “Probably the most important function of the ‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ,’ which can only be inferred from indirect evidence, is that it helped to ᴀssuage people’s fears about the unknowns of death,” Scalf said, noting that wealthy ancient Egyptians also arranged to have their bodies mummified and get their coffins decorated with religious texts in an effort to control what happened to them once they died.

Additionally, the spells in the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” could be used when a person was still alive. “Most of the spells from the ‘Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ’ are not designed to ‘navigate’ the underworld,” Scalf said. “Most of the spells are about transformation and transcendent experience. In the earthly life, a ritualist may use rites and incantations to transcend everyday experience [use the spells in a ceremony to have a religious experience],” said Scalf said, noting that “many of the spells include instructions for how to use them on Earth” — which shows that they were likely used by living people too, Scalf said.

Many of these spells could then also be used in the afterlife, the Egyptians believed. “A person may use these same spells to help transform their existence, but in many ways it is a similar transcendent experience. The spells are largely about elevating to the plane of existence of the gods; only then would the person travel the underworld along with the gods themselves,” Scalf said.

COPIES FOR BURIAL

On the left, Osiris-Seker stands in a shrine in mummified form. The name Osiris-Seker represents the fusion of Seker, the god of death, with Osiris, the god of resurrection. The Papyrus of Ani ends with the tomb of Ani, the white building with the pyramidal top, located at the foot of the mountain of Amenta, at Thebes. Emerging from the mountain’s slope into a papyrus thicket is the head of Hathor in the form of the divine cow. This goddess, mistress of the necropolis, who welcomes the arrivals of the deceased to the underworld, is also ᴀssociated with the protection of women. Standing before a lavish presentation of luxuriant offerings is another manifestation of Hathor, known as Tawaret. She has the head and body of a hippopotamus, the legs of a lioness and the tail of a crocodile. (Image credit: Nastasic via Getty Images)

Many copies of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” that have been discovered were unearthed in tombs and were likely not read much. And many of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” manuscripts that survive today were probably not read much before they were buried with the deceased, Scalf told Live Science.

“The longest of the papyrus manuscripts is over thirty meters [98 feet] in length; it would have been a very difficult manuscript to navigate when reading. These manuscripts [found in tombs] were prestige copies, largely meant for deposition in the grave,” Scalf said.

Additionally, spells from the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” were not always written down on manuscripts. For instance, Scalf noted that the spells were sometimes written down on the bandages that wrapped a person’s mummy. They were also inscribed on the walls of tombs and even on Tutankhamun’s golden death mask.

It’s possible that people who couldn’t afford a copy of the spells may have had the spells read to them. “If you did not have a scroll in your tomb, hired priests or family members might have recited it for you during the funeral, or when visiting the tomb afterwards,” Lara Weiss, a curator of the Egyptian and Nubian collection at the Netherland’s National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, told Live Science in an email.

The last known copies of the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ” were created in the first or second century A.D., Scalf wrote in a study published in the book “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt.” Another series of funerary texts known as the “Books of Breathing” became popular in its place — which was derived, in part, from the “Book of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ,” Scalf wrote.