In 79 CE, Mount Vesuvius erupted with devastating consequences, wiping out the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and killing thousands. One victim, a man in his early twenties, was found in bed inside a building called the Collegium Augustalium. Scientists uncovered his remains in the 1960s and stumbled upon a baffling discovery—his skull contained pieces of what looked like black, glᴀss-like material. A recent study published in Scientific Reports offers new insights into how his brain might have undergone a remarkable transformation, turning to glᴀss through a process known as vitrification.

Victims of the Mount Vesuvius eruption in the “Boat Houses,” Herculaneum. Credit: Big Albert, Flickr

Victims of the Mount Vesuvius eruption in the “Boat Houses,” Herculaneum. Credit: Big Albert, Flickr

Scientists have debated for years about the glᴀssy substance in the man’s skull. They couldn’t agree on whether it was brain matter or something else. Most experts thought the pyroclastic flows—fast-moving currents of H๏τ gas and volcanic debris—that covered Herculaneum weren’t H๏τ enough to turn human tissue into glᴀss. But new research offers a different idea. Geologist and volcanologist Guido Giordano from Roma Tre University led this study. He and his team suggest that before the pyroclastic flows, a superheated ash cloud, reaching temperatures of at least 510°C (950°F), rapidly enveloped the city. This intense heat would have been enough to liquefy the brain, followed by an equally rapid cooling process that transformed the organic material into glᴀss.

The researchers supported their hypothesis by analyzing charcoal fragments found near the remains. These fragments showed signs of high heat followed by quick cooling. They also compared them to recent volcanic eruptions, such as Mount Unzen in Japan in 1991 and the Fuego volcano in Guatemala in 2018. Both of these eruptions produced similar superheated ash clouds.

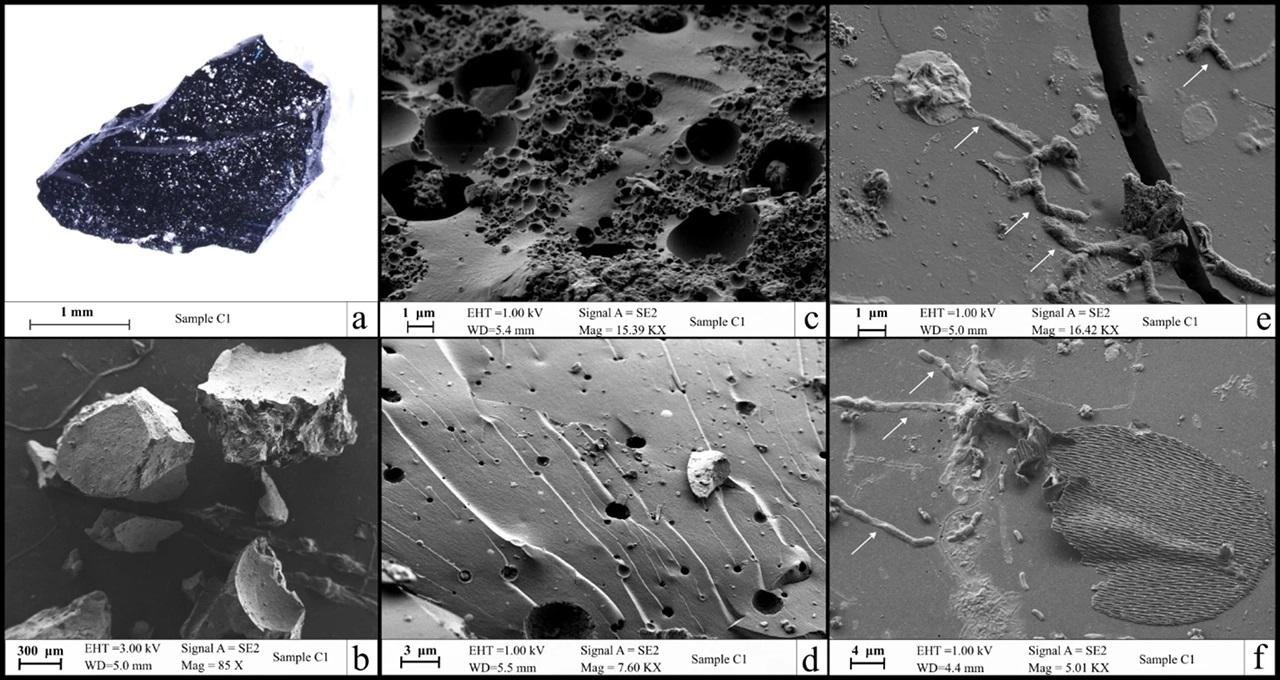

The team used advanced imaging techniques, including electron microscopy, to examine the glᴀssy fragments. Their analysis revealed preserved structures resembling nerve cells, strongly suggesting that the material was indeed brain tissue. “The glᴀss formed as a result of this process allowed for the integral preservation of biological brain material and its microstructures,” said forensic anthropologist Pier Paolo Petrone of Università di Napoli Federico II, one of the study’s lead researchers.

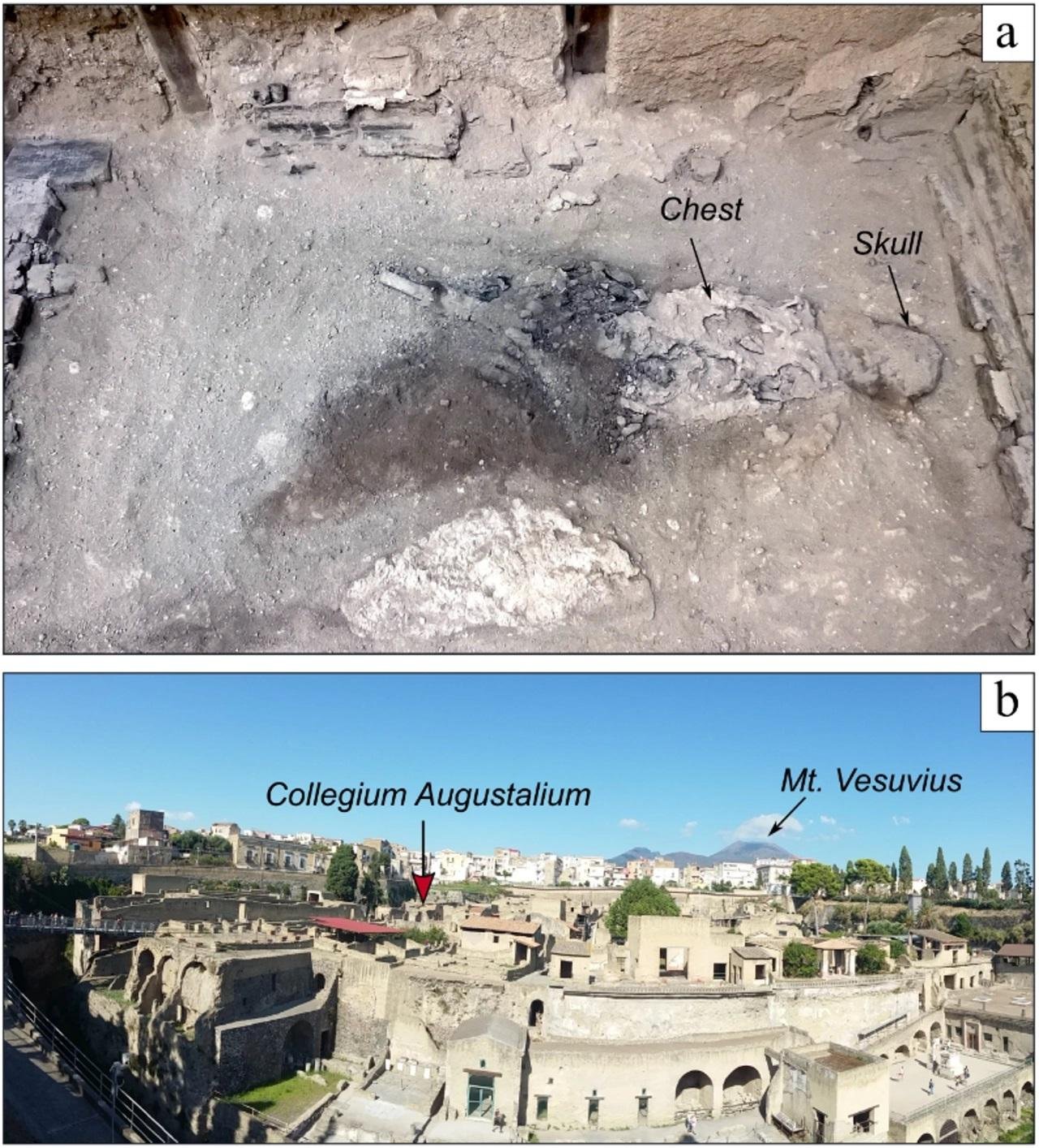

(a) Carbonized body of the guardian in his wooden bed within the Collegium Augustalium; the vitrified brain remains have been found within his skull. (b) Panoramic eastward view of Herculaneum ruins with Vesuvius volcano in the background, and the location of the Collegium Augustalium within the city. Credit: G. Giordano et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

(a) Carbonized body of the guardian in his wooden bed within the Collegium Augustalium; the vitrified brain remains have been found within his skull. (b) Panoramic eastward view of Herculaneum ruins with Vesuvius volcano in the background, and the location of the Collegium Augustalium within the city. Credit: G. Giordano et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

This discovery marks the first known case of human brain vitrification under natural conditions. Scientists have long understood that glᴀss formation requires specific conditions: a rapid temperature increase followed by equally fast cooling, preventing crystallization. While vitrified wood has occasionally been found at archaeological sites in Herculaneum and Pompeii, no human or animal remains have ever undergone this transformation before.

The team also explained why only the brain was preserved in this state. The intense heat destroyed bones and other soft tissues. However, the skull might have provided a degree of protection and allowed the brain to remain partially intact until it was rapidly cooled by the dissipating ash cloud.

Images at different magnifications of the sample. Credit: G. Giordano et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

Images at different magnifications of the sample. Credit: G. Giordano et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

Even with this new convincing proof, a few experts still doubt the findings. Alexandra Morton-Hayward, a molecular archaeologist at Oxford University, had earlier questioned whether the glᴀssy material was actually brain matter. In a 2020 paper published in Science & Technology of Archaeological Research, she and her team argued that the pyroclastic flows at Herculaneum weren’t H๏τ enough, nor did they cool rapidly enough, to cause vitrification. They also noted that external researchers couldn’t get samples for independent analysis.

The debate over the “glᴀss brain” is likely to continue as more studies are conducted. As scientific techniques advance, further research may yet uncover additional cases of this rare phenomenon.

More information: Giordano, G., Pensa, A., Vona, A. et al. (2025). Unique formation of organic glᴀss from a human brain in the Vesuvius eruption of 79 CE. Sci Rep 15, 5955. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88894-5