A team of archaeologists has made a breakthrough in Iraq’s Western Desert, where seven Paleolithic sites have been discovered comprising over 850 stone tools. Led by Ella Egberts from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), this research was undertaken in late 2024 in a pilot project investigating the geomorphological history of the region and ᴀssessing the potential for the preservation of ancient archaeological sites.

A Lower Paleolithic hand axe. Credit: VUB / Ella Egberts

A Lower Paleolithic hand axe. Credit: VUB / Ella Egberts

In the Al-Shabakah region, during the Pleistocene, there was a vast lake. The surroundings and the now-dry lake bed, crisscrossed with ancient dry riverbeds known as wadis, yielded many artifacts. The finds included Lower Paleolithic handaxes, potentially dating back to 1.5 million years, as well as Middle Paleolithic Levallois reduction flakes from around 300,000 to 50,000 years ago.

“Our targeted fieldwork led to the discovery of seven Paleolithic sites in an area of 10 by 20 km,” said Egberts in a statement. “One location was selected for systematic research to determine the spatial distribution of Paleolithic material and to conduct preliminary technological and typological analyses.”

Egberts, along with Jaafar Jotheri from the University of Al-Qadisiyah and Andreas Nymark from the University of Leicester, believes that further excavation in the area will yield even more significant findings. “The other sites deserve equally thorough systematic investigation, which will undoubtedly yield similar amounts of lithic material,” she noted. The research team intends to expand their study area and conduct in-depth artifact analysis to facilitate a deeper understanding of human evolution and behavior on the Arabian Peninsula.

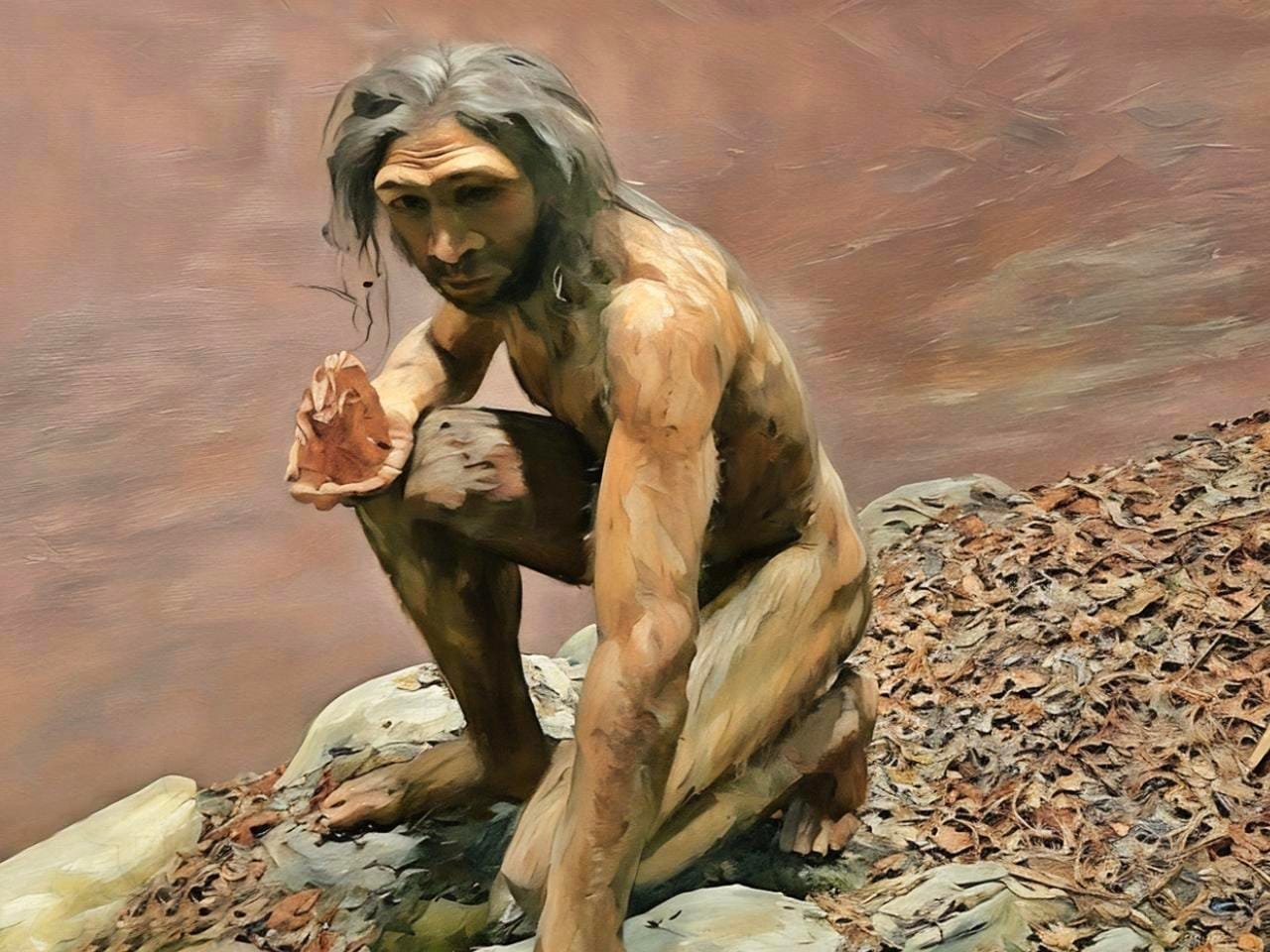

An artistic representation of Homo erectus holding an Acheulean hand axe. Archaeology News Online Magazine

An artistic representation of Homo erectus holding an Acheulean hand axe. Archaeology News Online Magazine

Three archaeology students from Iraq participated in the fieldwork. They were taught aspects of geoarchaeology and Paleolithic archaeology. The team also hosted a workshop at Al-Qadisiyah University to inspire more students and academics to explore Iraq’s prehistoric past.

The findings were presented to a diverse audience, including a multidisciplinary academic gathering at a conference in Karbala and a public event at the Writers’ Union in Najaf. Egberts and her team also seized the opportunity to show local elementary school children the prehistoric flint discoveries, fostering a new generation’s interest in archaeology.

The project was funded by the British Insтιтute for the Study of Iraq and awarded to Egberts through an honorary fellowship at the University of Leicester. Her next steps will include the reconstruction of environmental changes during the Pleistocene and the study of early human life and behavior in the Western Desert.

More information: Vrije Universiteit Brussel