The 31-year-old find of the Alps iceman has been studied once more. While Ötzi is unique, the conditions that preserved it are not, according to the researchers.

Ötzi the ice mummy. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ötzi the ice mummy. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

In September 1991, two German tourists exploring the Tyrolean Alps between Italy and Austria discovered a human corpse. Archaeologists later revealed the body, which had been sH๏τ in the back with an arrow, was around 5,300 years old. The body had been preserved for centuries by the ice, snow, sun, wind, and other conditions of the high-alpine environment.

The ice mummy known as Ötzi, is one of the world’s oldest and best preserved mummies. When archaeologists first began to ponder the conditions that preserved Ötzi, one accepted theory was that the iceman was running away from something or someone, probably a conflict, and decided to hide out in the mountains. He died there and was quickly buried in the winter snow. Ötzi fell into a shallow gully, which protected him from glacier movement.

31 years after the discovery, a new study suggests that everything archaeologists thought they knew about the 5,300-year-old corpse’s preservation was incorrect. The study, conducted by a team of researchers from Norway, Switzerland, and Austria, was published in the journal “The Holocene.”

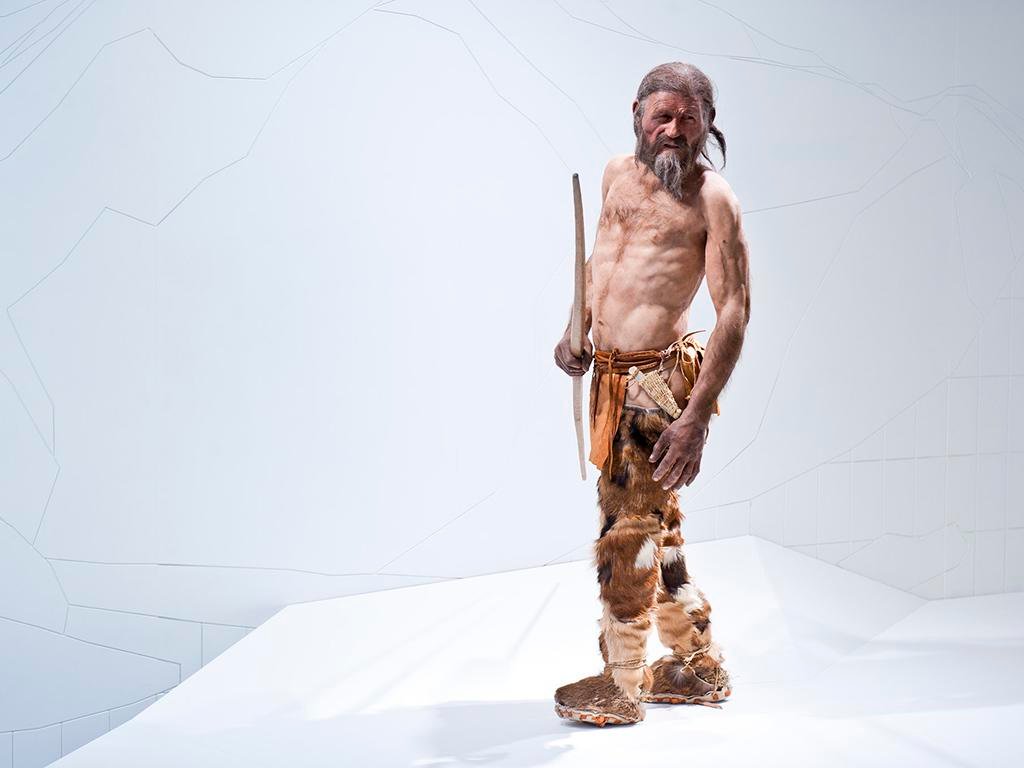

This reconstruction of Ötzi. Credit: OetziTheIceman, Flickr

This reconstruction of Ötzi. Credit: OetziTheIceman, Flickr

Archaeologists and glaciologists have discovered that the original explanation of how Ötzi was preserved for so long has not stood the test of time and that the official story must be rewritten.

Based on radiocarbon dating and other analyses of the leaves, seeds, moss, grᴀss, and dung found near his body, researchers believe Ötzi actually died in the spring, rather than the fall, which implies his corpse was exposed during the summer.

Because some of these organic materials were found to be younger than Ötzi, the researchers believe the site was open to the air on multiple occasions during the last 5,300 years. This all points to a different story: Ötzi was regularly exposed to the elements.

Lars Pilø, an archaeologist with the Oppland County Glacier Archaeological Program in Norway, and colleagues has reviewed the available research on Ötzi.

“The big test is to imagine that Ötzi was found today,” says Pilø to ScienceNorway. “With everything we now know about how glacial archaeological localities work, would anybody have come up with this theory? The answer to that is no. We don’t need the string of miracles, Ötzi was preserved by regular natural processes.”

The new study also examined the complete find and the find site in light of current glacial archaeology understanding and methodology. Finally, glaciologists compared old and newer maps, as well as mountain height charts, to determine how thick the ice covering Ötzi actually was.

Though in 1990s, researchers thought Ötzi’s preservation was a fluke, that now seems not to be the case. “The find circumstances of Ötzi are quite normal for glacial archaeology,” the researchers write in their paper. “The chances of finding another prehistoric human body in a similar topographical setting should therefore be higher than previously believed, since a string of special circumstances is not needed for the preservation of this type of find, and relevant locations are now affected by heavy melt events.”

Since Ötzi’s discovery, archaeologists have found numerous human bodies, horse remains, skis, hunting gear, and other historic items in melting glaciers.

More information: Pilø, L., Reitmaier, T., Fischer, A., Barrett, J. H., & Nesje, A. (2022). Ötzi, 30 years on: A reappraisal of the depositional and post-depositional history of the find. The Holocene, 0(0).