Scientists have uncovered the substances and concoctions ancient Egyptians used to mummify the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, from the remnants of an embalming workshop.

Vessels from an ancient Egyptian embalming workshop. Credit: M. Abdelghaffar/Saqqara Saite Tombs Project

Vessels from an ancient Egyptian embalming workshop. Credit: M. Abdelghaffar/Saqqara Saite Tombs Project

Mummification was a spiritual practice with deep meaning for the ancient Egyptians. According to ancient texts, it took 70 days of rituals and invocations to prepare the deceased for an eternal afterlife.

It also required specialized skills, extensive ingredient lists, and a professional group of embalmers who were steeped in religious and chemical knowledge.

Mummification specialists, accompanied by priests, concocted specific mixtures to embalm the head, wash the body, treat the liver and stomach, and prepare bandages to swath the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ body.

While researchers had previously known the names of substances used to embalm the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ from Egyptian texts, they could only guess at what compounds and materials they referred to until recently.

Now a team of scientists from Germany’s Tuebingen and Munich universities, in collaboration with the National Research Centre in Cairo, has found some answers by analysing the residue in 31 ceramic vessels uncovered at the Saqqara mummification workshop.

The extraordinary collection of pottery, dating from around 664-525 BCE, was discovered in 2016 at the bottom of a 13-meter (42-feet) well.

Researchers detected tree resin from Asia, cedar oil from Lebanon, and bitumen from the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ Sea within the vessels, showing how global trade helped embalmers source the best ingredients from around the world.

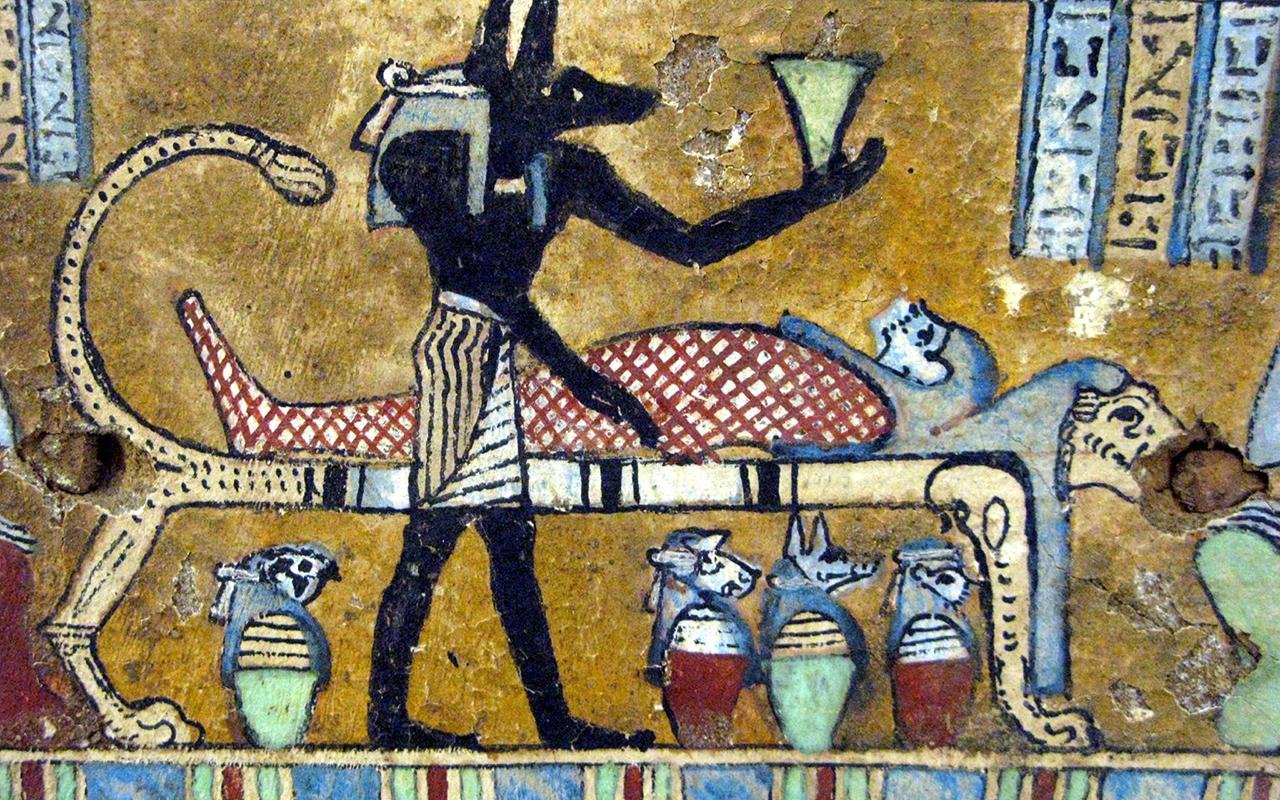

Wooden Sarcophagus, around 400 BCE; Anubis, supervisor of the mummification process. Underneath the bed are the four canopic vases, for the organs that were mummified separately. Credit: André, via flickr

Wooden Sarcophagus, around 400 BCE; Anubis, supervisor of the mummification process. Underneath the bed are the four canopic vases, for the organs that were mummified separately. Credit: André, via flickr

The substances had “antifungal, anti-bacterial properties” which helped “preserve human tissues and reduce unpleasant smells,” said the study’s lead author, Maxime Rageot.

“Ancient Egyptian embalmers had extensive chemical knowledge and knew what substances to put on the skin to preserve it, even without knowing about bacteria and other microorganisms,” Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, said at a news conference.

More information: Rageot, M., Hussein, R.B., Beck, S. et al. (2023). Biomolecular analyses enable new insights into ancient Egyptian embalming. Nature.