A recent study has successfully reconstructed the partially impaired skull of a great ape species, Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, that lived approximately 12 million years ago.

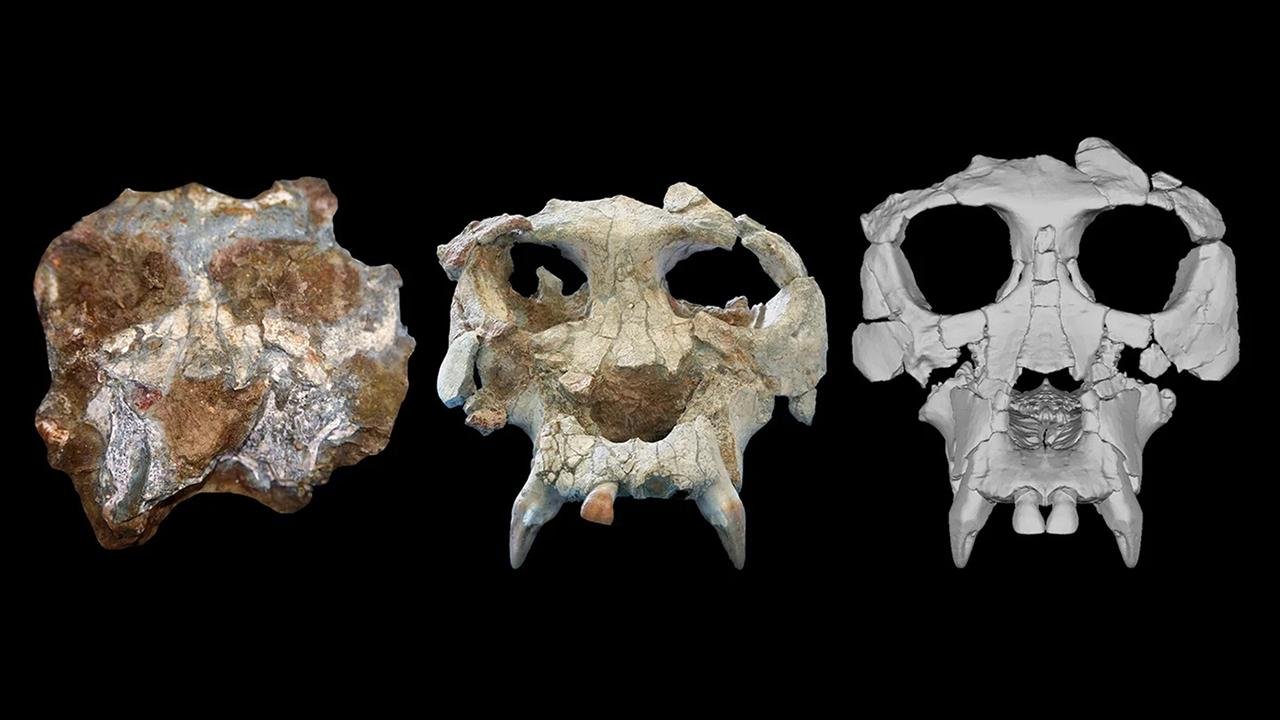

A composite of three images shows, from left, the Pierolapithecus cranium shortly after discovery, after initial preparation, and after virtual reconstruction. Credit: David Alba (left), Salvador Moyà-Solà (middle), Kelsey Pugh (right)

A composite of three images shows, from left, the Pierolapithecus cranium shortly after discovery, after initial preparation, and after virtual reconstruction. Credit: David Alba (left), Salvador Moyà-Solà (middle), Kelsey Pugh (right)

This ancient species, which lived in northeastern Spain around 12 million years ago, may hold crucial insights into the evolutionary relationships between great apes and humans. The study, led by researchers from the American Museum of Natural History, Brooklyn College, and the Catalan Insтιтute of Paleontology Miquel Crusafont, used advanced X-ray imaging to provide a three-dimensional image of Pierolapithecus’ face, helping to address ongoing debates about its evolutionary place.

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus was first described in 2004 and is a species from the Middle Miocene period, representing a diverse group of now-extinct ape species that lived in Europe from 15 to 7 million years ago. One of the remarkable aspects of this species is that it is known from a cranium and partial skeleton of the same individual, making it a rarity in the fossil record. This completeness is essential for accurately placing the species on the hominid family tree.

The fossil record for the evolution of apes and humans is often fragmentary and includes incomplete or distorted specimens, complicating efforts to establish the evolutionary relationships among these species. According to Ashley Hammond, an ᴀssociate curator and chair of the Museum’s Division of Anthropology, this is a persistent challenge in the study of apes and human evolution.

In the case of Pierolapithecus, the cranium was damaged, and some key features were missing, making it difficult to determine its place in the evolutionary tree. However, the researchers utilized advanced micro CT scanning technology to virtually reconstruct the cranium and analyze its morphology within an evolutionary framework. Their results are consistent with the hypothesis that Pierolapithecus represents one of the earliest members of the great ape and human family.

The reconstructed cranium of Pierolapithecus reveals that it shares similarities in overall face shape and size with both fossilized and living great apes. However, it also displays distinct facial features not found in other Middle Miocene apes. The researchers’ evolutionary modeling suggests that Pierolapithecus’ cranium is more similar in shape and size to the ancestor from which both living great apes and humans evolved, placing it closer to the root of the evolutionary tree.

This research provides a valuable contribution to our understanding of primate evolution, especially the relationships between different primate species. It helps to clarify the mosaic nature of hominid evolution, highlighting the significant features of Pierolapithecus as a basal member of the great ape and human family. The findings give information about the evolutionary transition from an orthograde (upright) body plan to suspensory adaptations, shedding light on the ways these ancient species moved in their environments.

More information: Pugh, K. D. et al. (2023). The reconstructed cranium of Pierolapithecus and the evolution of the great ape face. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(44), e2218778120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2218778120