A dig in northern Iraq has unearthed a 2,700-year-old alabaster sculpture of the winged ᴀssyrian deity Lamᴀssu.

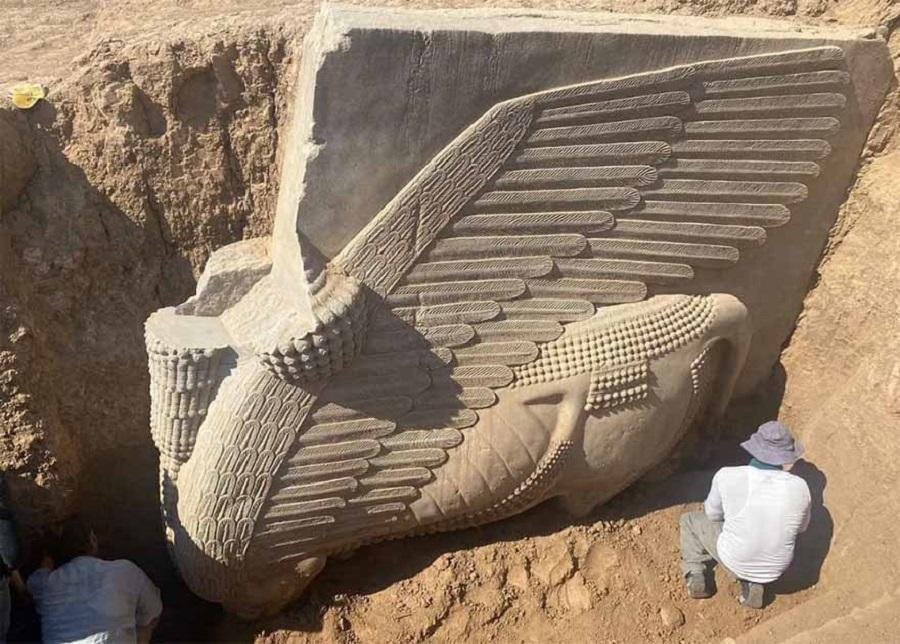

The alabaster Lamᴀssu sculpture was uncovered by archaeologists in northern Iraq. Credit: Mustafa Yahya

The alabaster Lamᴀssu sculpture was uncovered by archaeologists in northern Iraq. Credit: Mustafa Yahya

The sculpture, standing at an imposing 18 tons and measuring 3.8 by 3.9 meters (approximately 12.5 by 12.8 feet), remains largely intact, with only its head missing. The head, however, is not lost but is already part of the collection at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, having been confiscated by customs officers from smugglers in the 1990s.

Pascal ʙuттerlin, the French leader of the excavation team, expressed his astonishment at the sculpture’s size, saying, “I never unearthed anything this big in my life before.” He noted that such colossal findings are typically ᴀssociated with regions like Egypt or Cambodia. Furthermore, experts have been captivated by the sculpture’s meticulous attention to detail, describing it as “unbelievable.”

The Lamᴀssu is a mythical creature rooted in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and often depicted as a winged, human-headed bull or lion. These statues typically served as protective and guardian figures, placed at the entrances of palaces, temples, and significant structures to safeguard them from malevolent forces. With their combination of strength and intelligence, the Lamᴀssu symbolized both attributes.

This impressive Lamᴀssu sculpture originally graced the entrance to the ancient city of Khorsabad, located approximately 15 kilometers north of modern-day Mosul. It was commissioned during the reign of King Sargon II, who ruled from 722 to 705 BCE.

It has been an object of historical significance, with its first mention in the 19th century by French archaeologist Victor Place. However, it dropped from public records until the 1990s when Iraqi authorities recognized the need for “urgent intervention” to safeguard it.

Tragically, during this period, looters targeted the sculpture and stole its head, subsequently dismembering it to facilitate smuggling out of the country. The remaining body of the relief, however, managed to escape the destruction that the Islamic State jihadist group wrought in 2014 when it overran the area. Residents of the modern village of Khorsabad took measures to hide the sculpture before fleeing to government-held territory, preserving this invaluable piece of history.

The researchers now face the challenge of rejoining the sculpture’s head and body. The sculpture’s neck suffered damage when looters separated the head, requiring careful restoration. Once the restoration is complete, the fate of this remarkable Lamᴀssu sculpture will be a topic of consideration.