In 1934, a remarkable double burial was unearthed by German workers in Bad Dürrenberg, eastern Germany, at the spa gardens during construction. The grave, dating back to 7000-6800 BCE, held the remains of an adult woman and an infant.

The burial is part of an exhibit at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle (Saale) in Germany. Credit: Juraj Lipták, State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt

The burial is part of an exhibit at the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle (Saale) in Germany. Credit: Juraj Lipták, State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt

Recent genetic research has challenged previous ᴀssumptions and revealed fascinating details about the woman’s idenтιтy, her potential role as a shaman, and the extended familial ties with the buried child.

The woman, believed to be a shaman due to the presence of elaborate grave goods and her seated position, has been the subject of extensive genetic analysis.

“We sequenced the entire genome of this woman who lived [about] 9,000 years ago,” Wolfgang Haak, the group leader for the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Insтιтute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, told Live Science. The findings, presented in the Propylaeum conference proceedings, have uncovered intriguing details about her life and lineage.

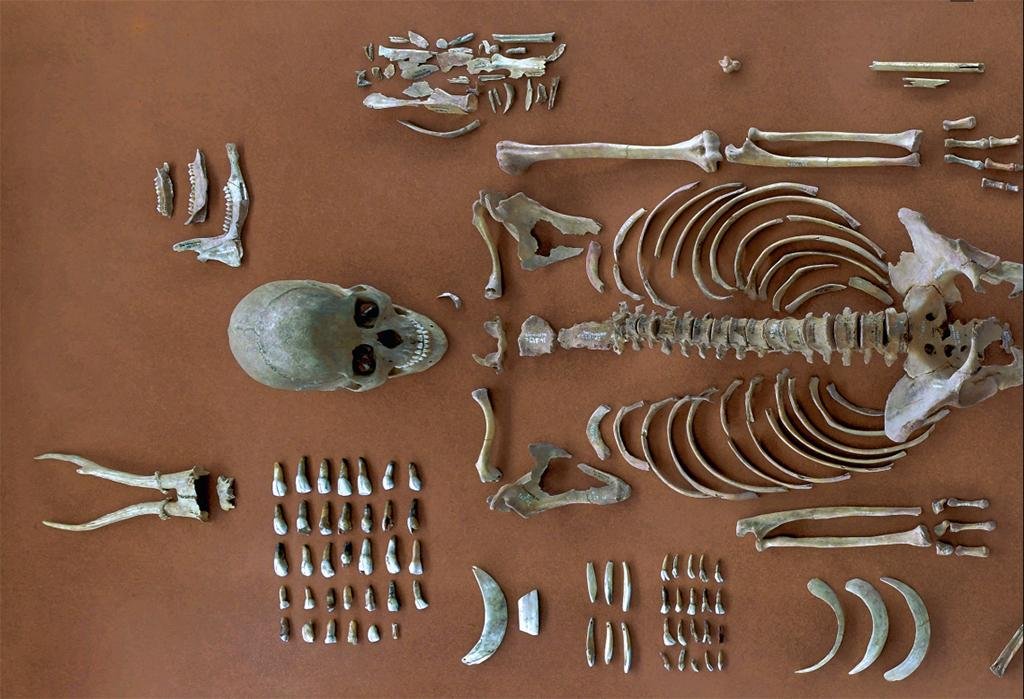

Credit: Orschiedt et al, Propylaeum (2023)

Credit: Orschiedt et al, Propylaeum (2023)

The genetic analysis revealed that the woman, aged 30 to 40 at the time of her death, belonged to the Western European hunter-gatherer population, which dominated central and western Europe at the end of the Upper Paleolithic and early Holocene. She stood approximately 5 feet, 1 inch tall, with darker hair and skin compared to modern Europeans, complemented by likely lighter, bluish eyes – characteristics common among Western European hunter-gatherers.

Notably, the woman exhibited unique physical traits, including missing muscles in her lower extremities and an abnormal development in the blood vessel of her skull. Jörg Orschiedt, an archaeology professor at Free University Berlin and co-author of the research, highlighted that despite these anomalies, she was far from being physically restricted or disabled.

A rare anatomical anomaly at the base of her skull, potentially influencing her status as a shaman, was also identified. Orschiedt explained, “A probable consequence is an involuntary eye flutter: a nystagmus. This appears irritating or uncanny to onlookers and has probably influenced her role as a shaman.”

Contrary to initial ᴀssumptions, the genetic analysis unveiled a surprising revelation about the woman’s relationship with the buried infant. Haak clarified, “It is possible that she was his (great-) great-great-great-grandmother in a line of generations, and that the boy was added many decades later to the grave of his ancestor.” This challenges the previously held belief that they were a mother-son duo, highlighting a unique familial connection spanning several generations.

The grave’s rich ᴀssemblage of artifacts, including flint blades, mussel shells, deer bones, and wild boar tusks, provided crucial context to the discovery. Haak stated: “Even though the discovery was made in the 1930s, the new research contributes a lot of new details to the find context, with a clear attribution to the Mesolithic, and paints a more detailed picture of the last European hunter-gatherer groups.”

Further excavations as part of preparations for the State Garden Exhibition 2024 brought additional revelations about the burial. The woman’s skeleton, characterized by its gracile nature and distinctive features, was accompanied by a myriad of new finds, including pierced animal teeth, remains of fauna, and human skeletal remains.

The study, authored by Jörg Orschiedt, Wolfgang Haak, Holger Dietl, Andreas Siegl, and Harald Meller, utilized advanced genetic techniques to explore the relationship between the woman and the infant. The researchers employed a method to detect biological higher degree relatedness, known as idenтιтy-by-descent (IBD) tracts, confirming a fourth or fifth-degree relation between the two individuals, equivalent to four or five generations apart.

The findings arising from this Mesolithic burial, challenge preconceived notions about familial connections within ancient hunter-gatherer communities in Central Europe.

More information: Orschiedt, J. et al, (2023), The Shaman and the Infant: The Mesolithic Double Burial from Bad Dürrenberg, Germany, Propylaeum. DOI: 10.11588/propylaeum.1280.c18002