Archaeologists from the University of Copenhagen have made a chilling discovery, confirming ancient Greek historian Herodotus’ accounts of Scythian warriors using the skin of their defeated enemies to craft leather items, including arrow quivers.

The Scythians, a nomadic group inhabiting the Pontic-Caspian steppe from 700 BCE to 300 BCE, were renowned for their ferocity in battle and equestrian prowess. While previous knowledge about them has been limited to their reputation as fearsome warriors, the recent discovery provides tangible evidence of their macabre practices.

The Scythians, a nomadic group inhabiting the Pontic-Caspian steppe from 700 BCE to 300 BCE, were renowned for their ferocity in battle and equestrian prowess. While previous knowledge about them has been limited to their reputation as fearsome warriors, the recent discovery provides tangible evidence of their macabre practices.

In a comprehensive project reported in the journal PLOS ONE, a multi-insтιтutional team of anthropologists, led by Dr. Luise Ørsted Brandt, examined 45 leather samples collected from 14 Scythian dig sites in southern Ukraine. The majority of these samples were derived from common animals such as horses, cattle, goats, and sheep, likely reflecting the Scythians’ nomadic lifestyle and dependence on herded animals.

However, the shockingly grisly revelation came with the identification of two quivers containing human skin.

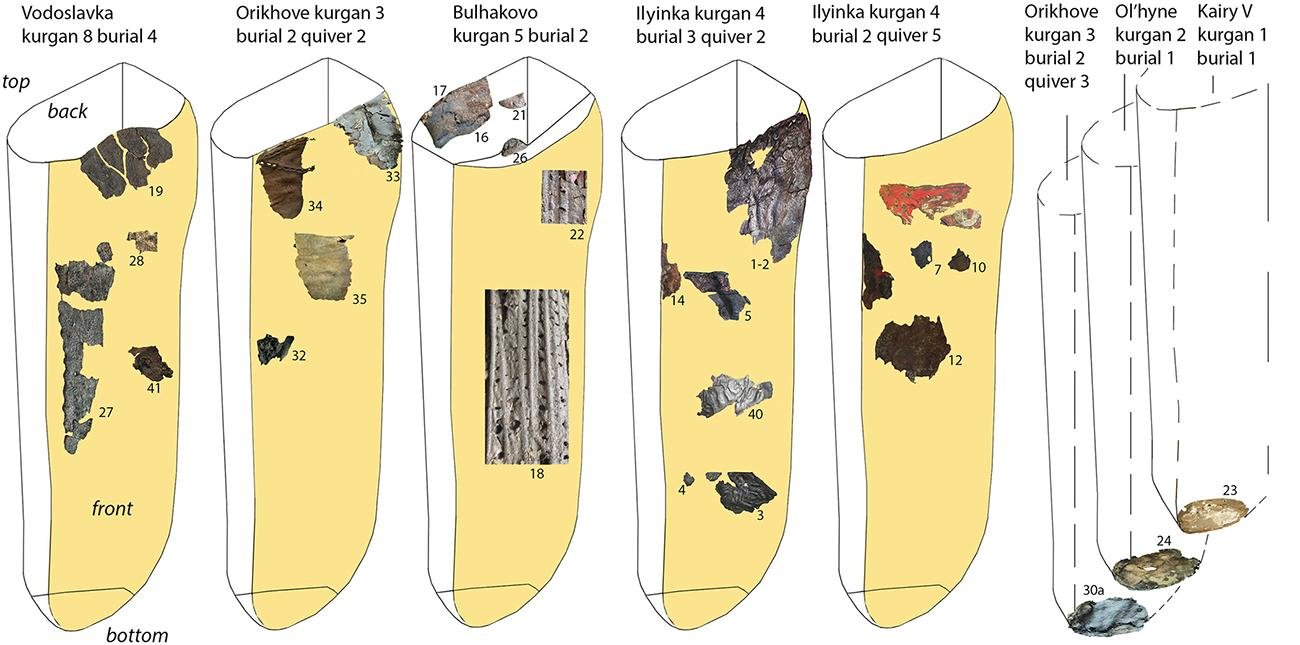

A selection of the leather object fragments analyzed in this study: 1. Ilyinka kurgan 4 burial 2; 2. Ilyinka kurgan 4 burial 3; 3. Vodoslavka kurgan 8 burial 4; 4. Orikhove kurgan 3 burial 2; 5. Zelene I kurgan 2 burial 3; 6. Kairy V kurgan 1 burial 1; 7. Ol’hyne kurgan 2 burial 1; 8. Bulhakovo kurgan 5 burial 2; 9. Zolota Balka kurgan 13 burial 7. Credit: M. Daragan, PLOS ONE (2023)

A selection of the leather object fragments analyzed in this study: 1. Ilyinka kurgan 4 burial 2; 2. Ilyinka kurgan 4 burial 3; 3. Vodoslavka kurgan 8 burial 4; 4. Orikhove kurgan 3 burial 2; 5. Zelene I kurgan 2 burial 3; 6. Kairy V kurgan 1 burial 1; 7. Ol’hyne kurgan 2 burial 1; 8. Bulhakovo kurgan 5 burial 2; 9. Zolota Balka kurgan 13 burial 7. Credit: M. Daragan, PLOS ONE (2023)

“The surprise discovery is the presence of two human skin samples, which for the first time provide direct evidence of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus’ claim that Scythians used the skin of their ᴅᴇᴀᴅ enemies to manufacture leather trophy items, such as quiver covers,” wrote the study authors.

Further examination of the human skin leather samples revealed that they were selectively used in the top parts of the quivers, while the rest of the quivers were made from animal leather. This suggests a deliberate and purposeful crafting of these quivers, possibly by individual archers using materials readily available at the time.

The use of human skin, while shocking, isn’t without precedent in history. Various cultures have used human skin for bookbinding and other macabre artifacts. Yet, in the context of the Scythians, it may have had a dual purpose: to honor the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ or to signify domination over their enemies.

Graphic reconstruction of quivers with approximate location of their extant fragments; numbers indicate sample numbers. Credit: M. Daragan, PLOS ONE (2023)

Graphic reconstruction of quivers with approximate location of their extant fragments; numbers indicate sample numbers. Credit: M. Daragan, PLOS ONE (2023)

The archaeological findings also align with other customs described by Herodotus, indicating the Scythians’ complex and elaborate funerary practices. Recent re-investigations of royal Scythian burial mounds in southern Ukraine have unveiled large funerary feasting areas, where men, women, and children were buried as part of the rituals for the royal occupant.

The Scythians were a mysterious group, with little known about their daily life. Previous stories pᴀssed down by the ancient Greeks indicated gruesome practices such as drinking the blood of enemies and using scalps as hand towels. While Herodotus’ historical accounts have often faced criticism for blending fact and folklore, in this instance, the scientific validation of the Scythians’ use of human skin for leather items brings his ancient words into stark and horrifying reality.

More information: Brandt LØ, Mackie M, Daragan M, Collins MJ, Gleba M (2023) Human and animal skin identified by palaeoproteomics in Scythian leather objects from Ukraine. PLoS ONE 18(12): e0294129.