An international team of archaeologists, led by Mouncef Sedrati, an ᴀssociate professor of coastal dynamics and geomorphology at the University of Southern Brittany in France, has uncovered one of the largest and best-preserved trackways in the world on a beach in Morocco.

The area delimited by the dotted red line corresponds to the footprint discovery zone. The vertical white line corresponds to the location of the sediment log analyzed in this study. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

The area delimited by the dotted red line corresponds to the footprint discovery zone. The vertical white line corresponds to the location of the sediment log analyzed in this study. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

The findings, detailed in a study published in Scientific Reports, provide a unique glimpse into the activities of early modern humans approximately 90,000 years ago during the Late Pleistocene

The accidental discovery occurred in 2022 when Sedrati and his team were studying boulders near the northern tip of North Africa. While waiting for the tides to change, Sedrati suggested exploring another beach, where the researchers stumbled upon the first set of footprints.

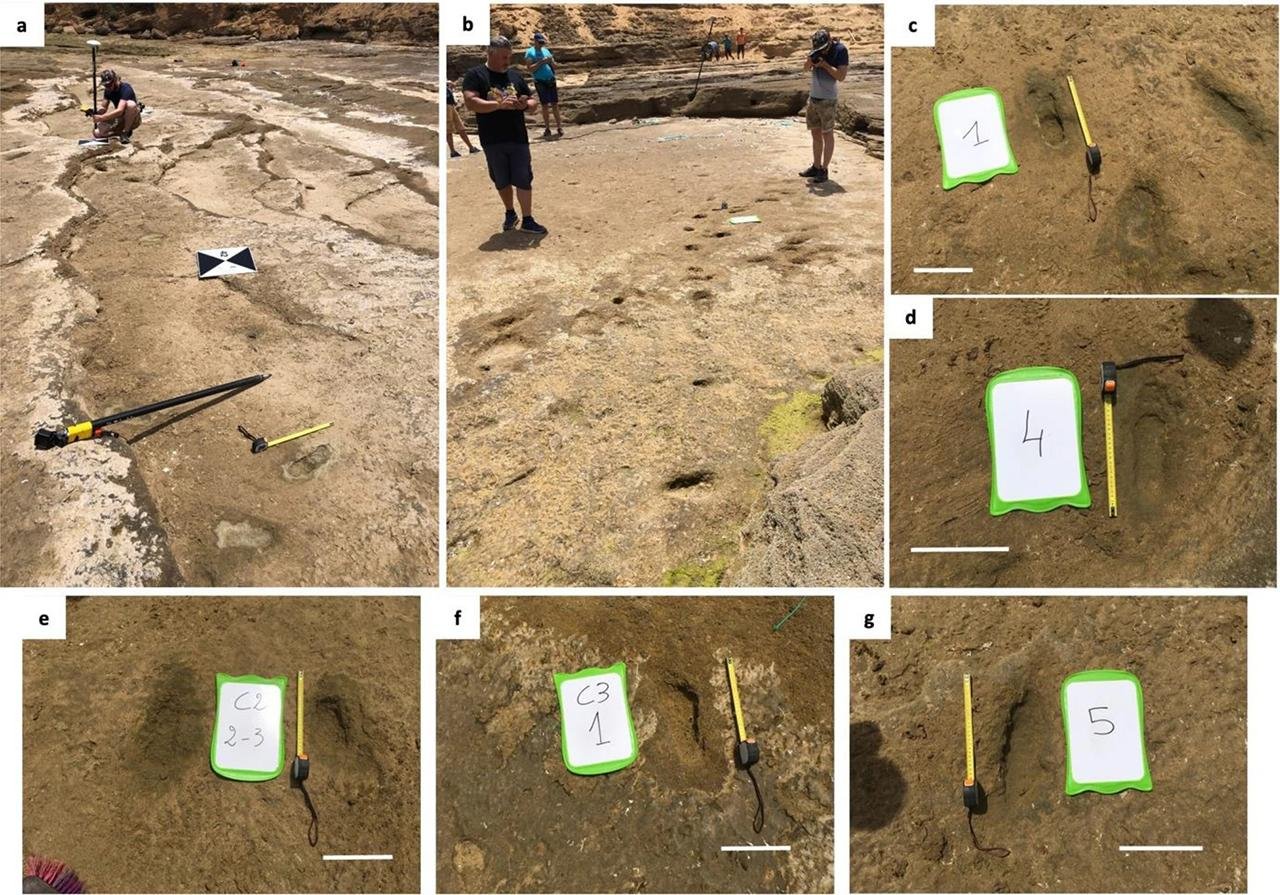

Further examination revealed a total of 85 human footprints, forming two distinct trails, believed to have been imprinted by at least five individuals of various ages, including children, adolescents, and adults.

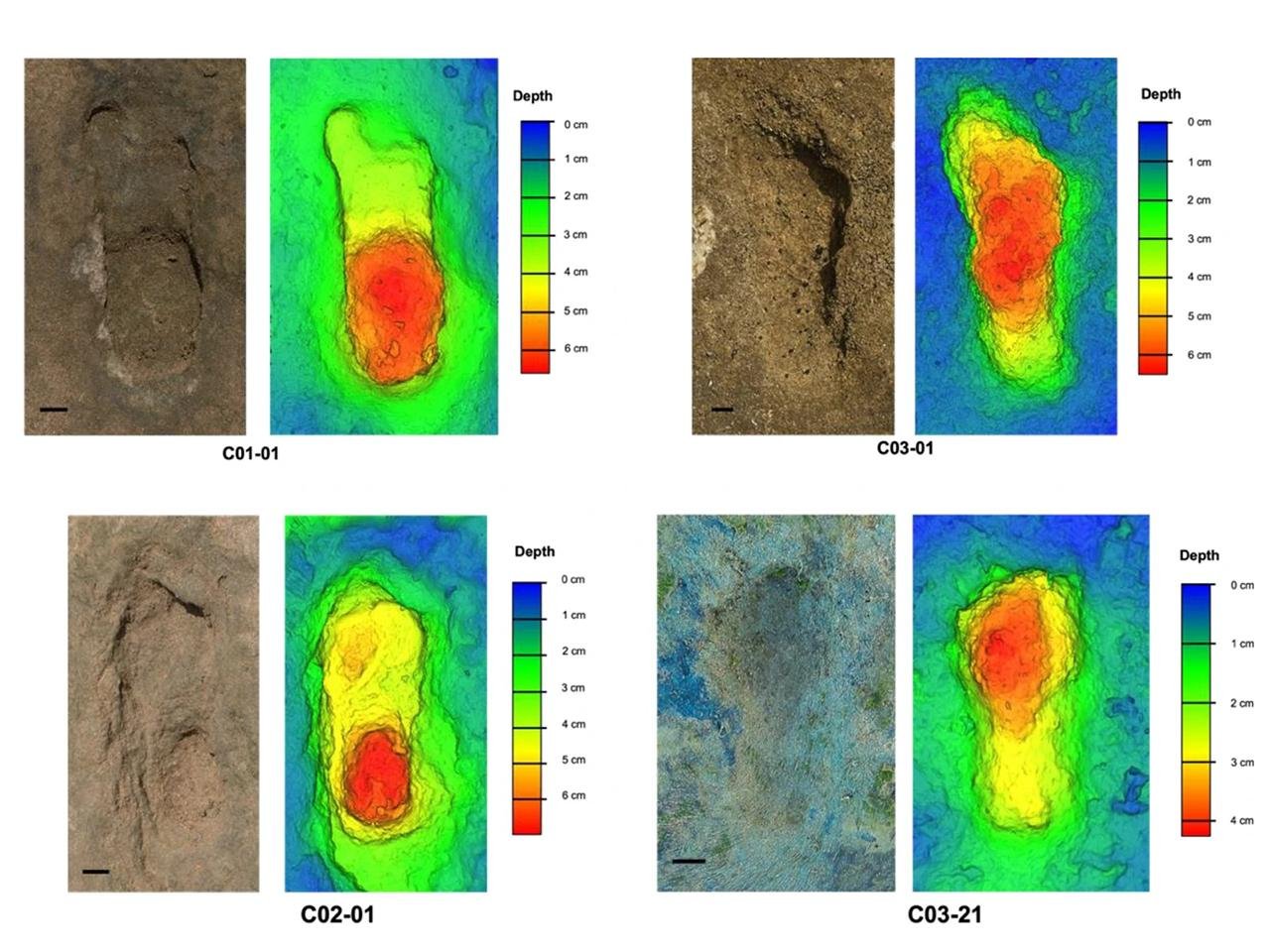

Hominin footprints from Larache. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

Hominin footprints from Larache. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

The trackway, the only known site of its kind in North Africa and the Southern Mediterranean from that time, has been dated using optically stimulated luminescence. By analyzing fine grains of quartz on the sandy beach, the researchers determined that the footprints were made around 90,000 years ago.

The exceptional preservation of the footprints can be attributed to the beach’s unique rocky platform covered in clay sediments, which created optimal conditions for the tracks to endure while the tides rapidly buried the rest of the beach.

These footprints represent one of the largest and best-preserved trackways ever found. The team’s meticulous on-site measurements, including the length and depth of the prints, provided information about the multigenerational group’s composition and approximate ages. Sedrati emphasized, “Based on the foot pressure and size of the footprints, we were able to determine the approximate age of the individuals.”

Images of some of the hominin tracks in Larache. (a) Two tracks side by side at the bottom of the pH๏τo, which also depicts a ground control point (chequered cardboard) for differential GPS surveying. (b) Two cross trackways and pH๏τography for 3D footprint modelling. (c) to (g) Detailed view of some footprints. White Scale bars = 20 cm. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

Images of some of the hominin tracks in Larache. (a) Two tracks side by side at the bottom of the pH๏τo, which also depicts a ground control point (chequered cardboard) for differential GPS surveying. (b) Two cross trackways and pH๏τography for 3D footprint modelling. (c) to (g) Detailed view of some footprints. White Scale bars = 20 cm. Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

The researchers remain intrigued about the purpose of the Ice Age group’s presence on the beach, with possibilities ranging from searching for food to cooling off or simply navigating through the area. However, the ongoing collapse of the rocky shore platform poses a threat to the site’s preservation, urging the team to act swiftly to unveil more details about the ancient humans’ history.

Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

Credit: Sedrati et al. Sci Rep (2024)

This discovery adds complexity to our understanding of early Homo sapiens movements. Dr. Sedrati was also part of a research crew that, in 2020, uncovered human and animal footprints in the Nefud Desert in Saudi Arabia, dating back around 120,000 years.

More information: Sedrati, M., Morales, J.A., Duveau, J. et al. (2024). A Late Pleistocene hominin footprint site on the North African coast of Morocco. Sci Rep 14, 1962. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-52344-5