Historians at the University of Göttingen have identified a medieval document in their collection as a forgery from the 18th century, crafted by the infamous Italian counterfeiter Domenico Cicci.

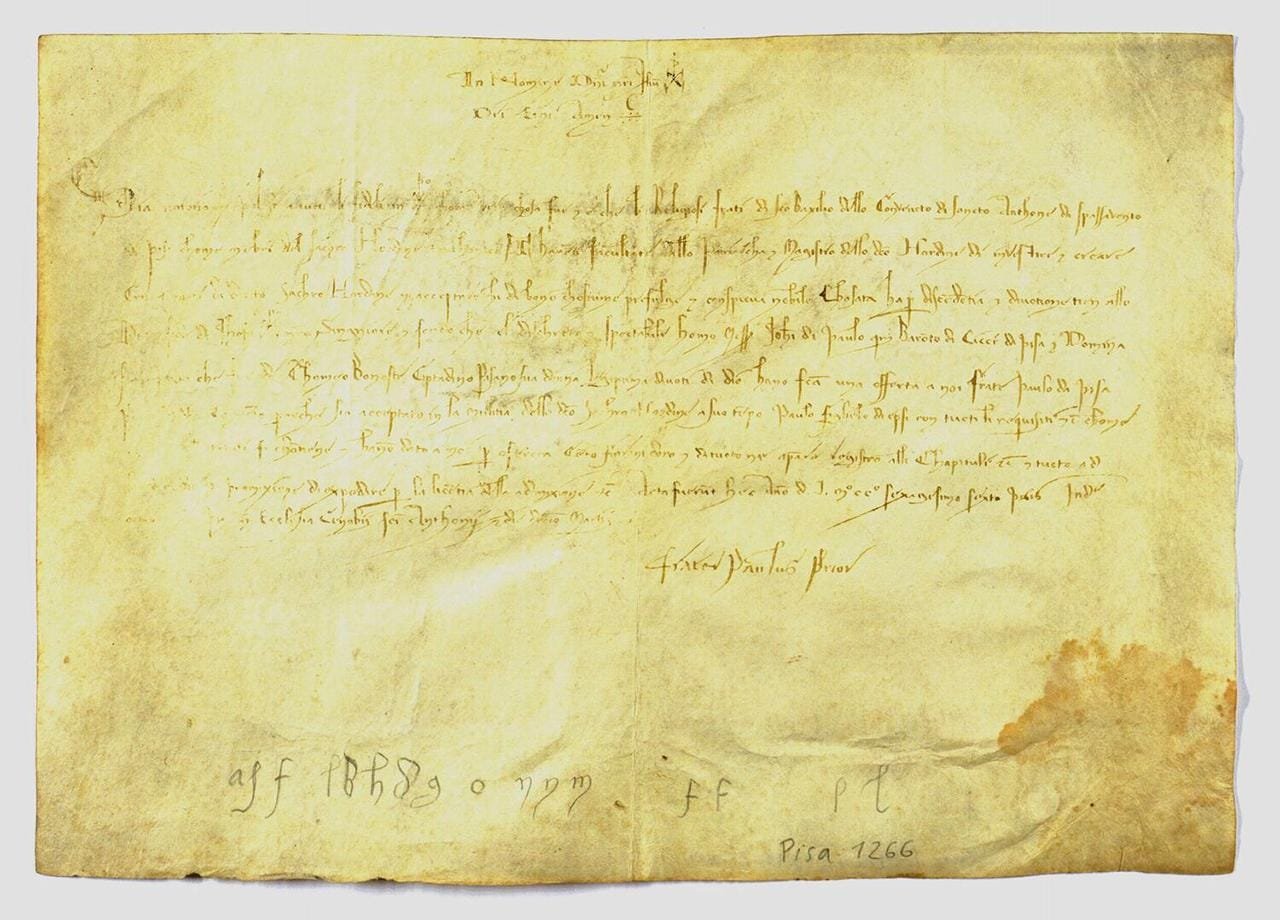

Forgery by Domenico Alessandro Cicci, probably from the period 1763-1769. Credit: Göttingen University’s Apparatus Diplomaticus

Forgery by Domenico Alessandro Cicci, probably from the period 1763-1769. Credit: Göttingen University’s Apparatus Diplomaticus

The discovery, made during preparations for the university’s Forum Wissen museum, sheds light on a scheme that aimed to elevate Cicci’s family into the ranks of nobility.

The document, which claimed to date back to 1266, stood out among the Göttingen collection because it was written in Italian rather than the typical Latin. However, its authenticity came into question due to its mention of a church in Pisa that was not constructed until the 14th century.

“This 18th-century forgery by an Italian counterfeiter almost led historians down the wrong track,” remarked Dr. Boris Gübele, a historian specializing in medieval and modern history at the University of Göttingen.

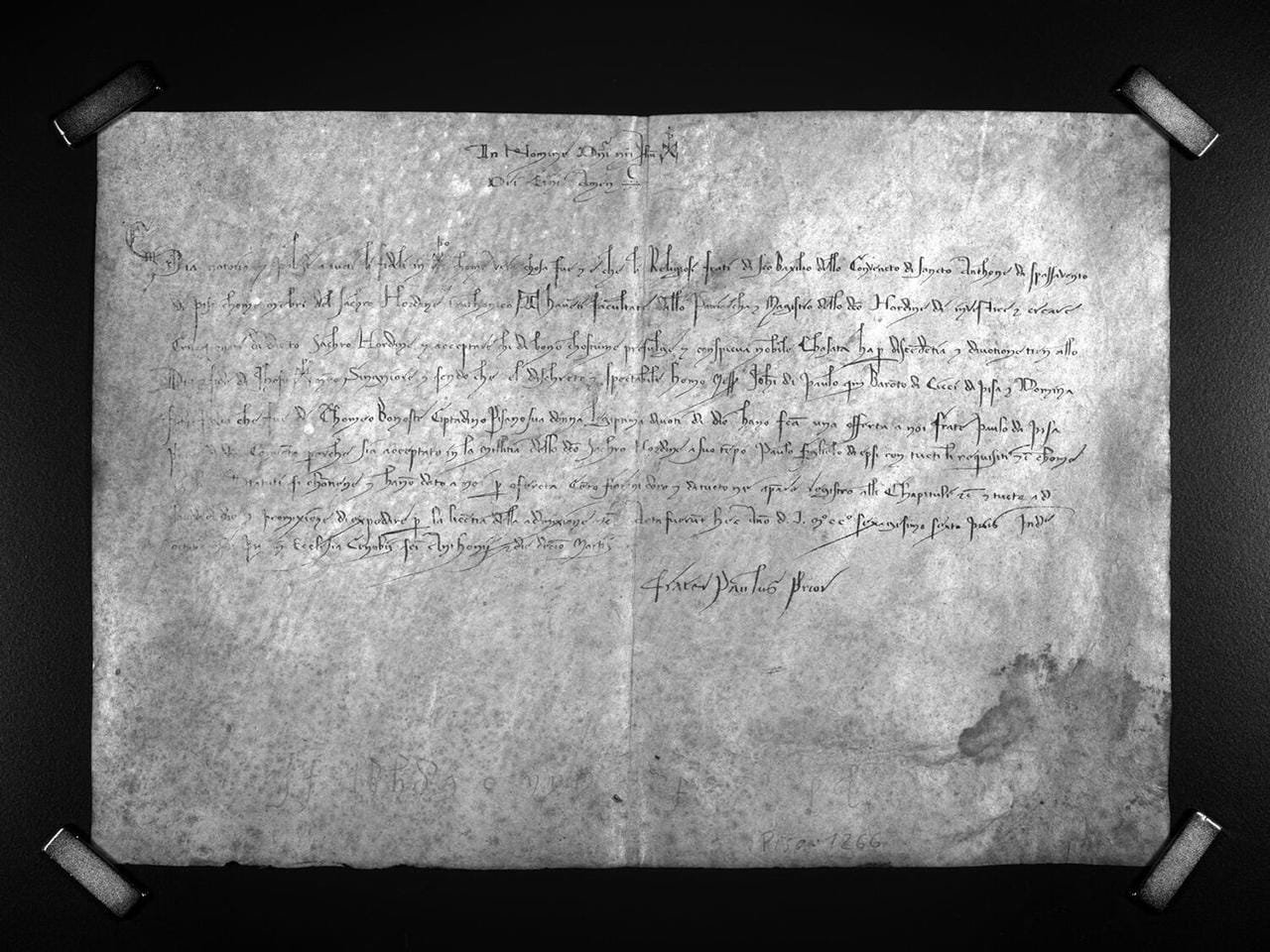

Image obtained using multispectral imagery, a technique which uses more than just the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum to reveal faded text. Credit: Göttingen University’s Apparatus Diplomaticus

Image obtained using multispectral imagery, a technique which uses more than just the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum to reveal faded text. Credit: Göttingen University’s Apparatus Diplomaticus

Gübele collaborated with Italian researchers to scrutinize the document, uncovering further inconsistencies that confirmed its forged nature. The text described a married couple from Pisa who pledged their son to a religious order supposedly connected to the anachronistic church. Upon closer examination, the team traced the document back to Cicci, who is known to have forged approximately 200 similar documents between 1763 and 1769.

Cicci’s forgeries often fabricated a lineage of prominence for his ancestors, portraying them as bishops, notaries, landowners, Crusaders, and even knights of various orders. This elaborate scheme succeeded in raising his family’s social status, enabling them to join the nobility.

According to Dr. Gübele, these forgeries had the potential to significantly mislead historical scholarship. “The claims in this document could have resulted in the church being re-dated, for instance,” he explained.

Many of his forged documents may still reside undetected in archives around the world, posing a challenge for historians and archivists alike. The forged document is now a subject of interest for its historical significance as a counterfeit and will likely feature prominently in the Forum Wissen museum’s exhibitions.

More information: University of Göttingen