A recent interdisciplinary study of ancient human remains from Kosenivka, Ukraine, has revealed new insights into the lives and deaths of individuals from the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, a Neolithic society that flourished in Eastern Europe between 5500 and 2750 BCE.

PH๏τo showing house 6 being excavated, in 2004. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

PH๏τo showing house 6 being excavated, in 2004. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

Archaeologists first uncovered the site in 2004, located about 115 miles south of Kyiv. The settlement was part of the Trypillia culture, known for creating some of the earliest “mega-sites” in prehistoric Europe, housing up to 15,000 inhabitants. Despite the extensive archaeological material left behind by the Trypillia people, human remains have been remarkably scarce—making the Kosenivka site a rare and valuable find.

Within a burned house, researchers discovered 50 bone fragments belonging to seven individuals, including two children, one adolescent, and four adults. Four of the individuals were heavily burned, while three were unburned and found outside the house. Radiocarbon dating revealed that six of the individuals likely perished between 3690 and 3620 BCE, while one person’s remains dated roughly 130 years later, suggesting a complex series of events.

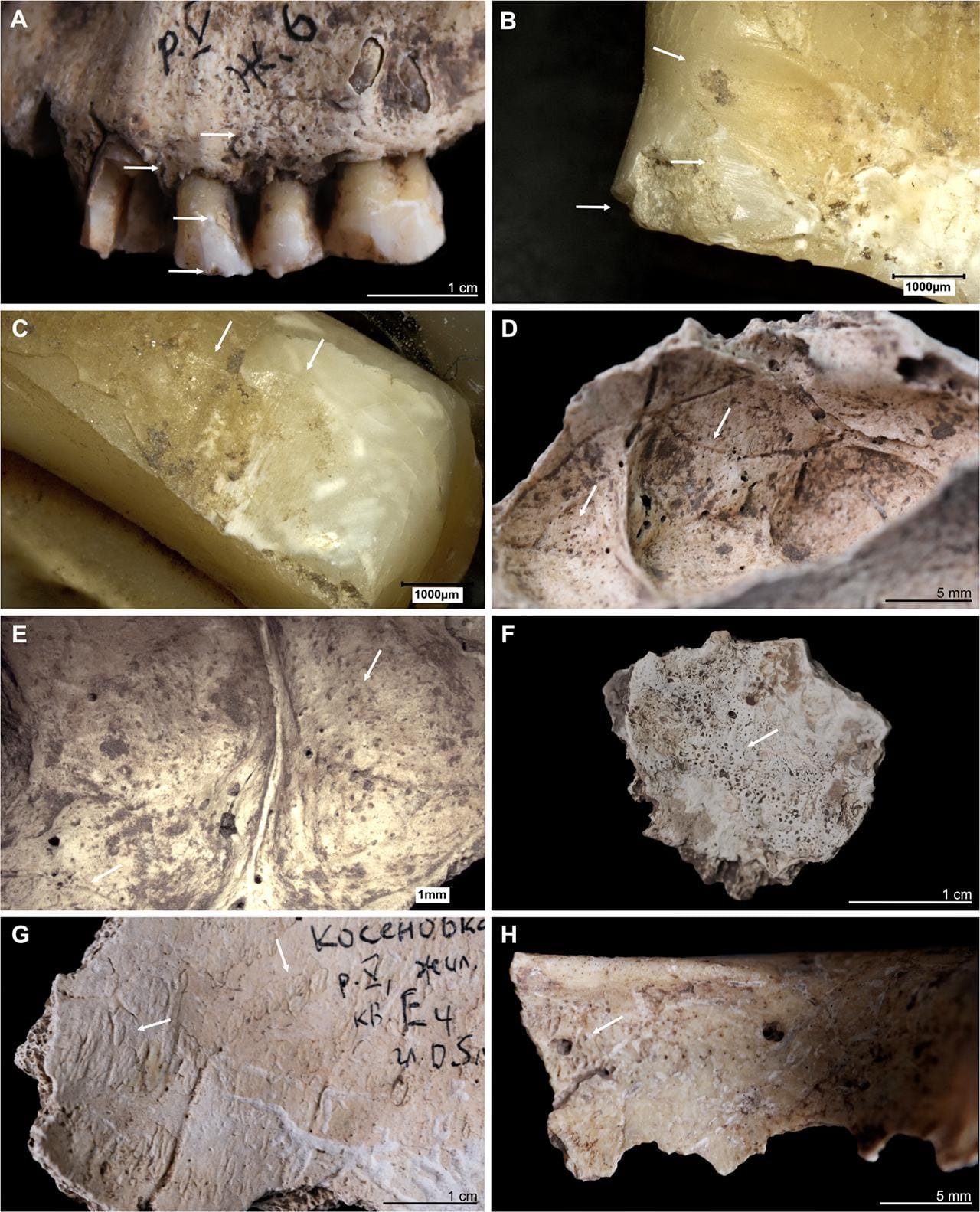

Microscopic analysis of the bones revealed that burning occurred shortly after death, indicating the fire may have been deliberate rather than accidental. Adding to the mystery, two adults exhibited unhealed cranial injuries, pointing to violent deaths.

Selection of oral and pathological conditions. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

Selection of oral and pathological conditions. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

Katharina Fuchs, a biological anthropologist at Kiel University and lead author of the study cautioned that the precise link between the fire and the apparent violence remains speculative.

Jordan Karsten, an archaeologist at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, who was not involved in the study, suggested intergroup conflict could explain the destruction. “It seems reasonable that the individuals recovered from Kosenivka were killed during a raid and that their house was lit on fire during the conflict,” Karsten told Live Science.

In addition to exploring the causes of death, the study also examined the dietary habits of the Kosenivka inhabitants. Stable isotopic analysis of human and animal remains, combined with archaeobotanical evidence, revealed that plant-based foods provided around 90% of their protein intake. Meat, surprisingly, contributed less than 10% to their diets, even though cattle were widely kept in the region.

Selection of larger fragments from the human bone ᴀssemblage. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

Selection of larger fragments from the human bone ᴀssemblage. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

“Despite the overwhelming dominance of animal bones at other settlement sites, our food web calculations clearly unmasked plants as the primary food source,” the researchers noted. Dental wear patterns also supported this finding, showing evidence of chewing grains and fibrous plant materials.

Trypillia cattle were primarily used for milk production and as a source of manure for fertilizing crops. “Even today, in farming societies without access to artificial fertilizer, large dung heaps are considered symbols of wealth,” the researchers explained.

The fragmented and burned bones at Kosenivka suggest a rare form of burial practice or ritual deposition. Typically, Trypillia burials were extramural, occurring outside settlements, making this case highly unusual.

Selection of cases of perimortem cranial trauma, showing location and osteological details of the lesions. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

Selection of cases of perimortem cranial trauma, showing location and osteological details of the lesions. Credit: K. Fuchs et al. PLoS ONE (2024), CC BY 4.0

“The isolated skull fragment from a later period could be part of a deliberate ritual deposition,” the researchers wrote. The whole collection of bones could be the result of a complex, multistage burial tradition.

Katharina Fuchs said: “Skeletal remains are real biological archives. Although researching the Trypillia societies and their living conditions in the oldest city-like communities in Eastern Europe will remain challenging, our ‘Kosenvika case’ clearly shows that even small fragments of bone are of great help.”

While the study sheds light on many aspects of Trypillia life, it leaves lingering questions about the reasons behind the violence and the specific circumstances of the fire.

The findings are published in PLOS ONE.

More information: Fuchs K, Hofmann R, Shatilo L, Schlütz F, Storch S, Chabanyuk V, et al. (2024) Life and death in Trypillia times: Interdisciplinary analyses of the unique human remains from the settlement of Kosenivka, Ukraine (3700–3600 BCE). PLoS ONE 19(12): e0289769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0289769