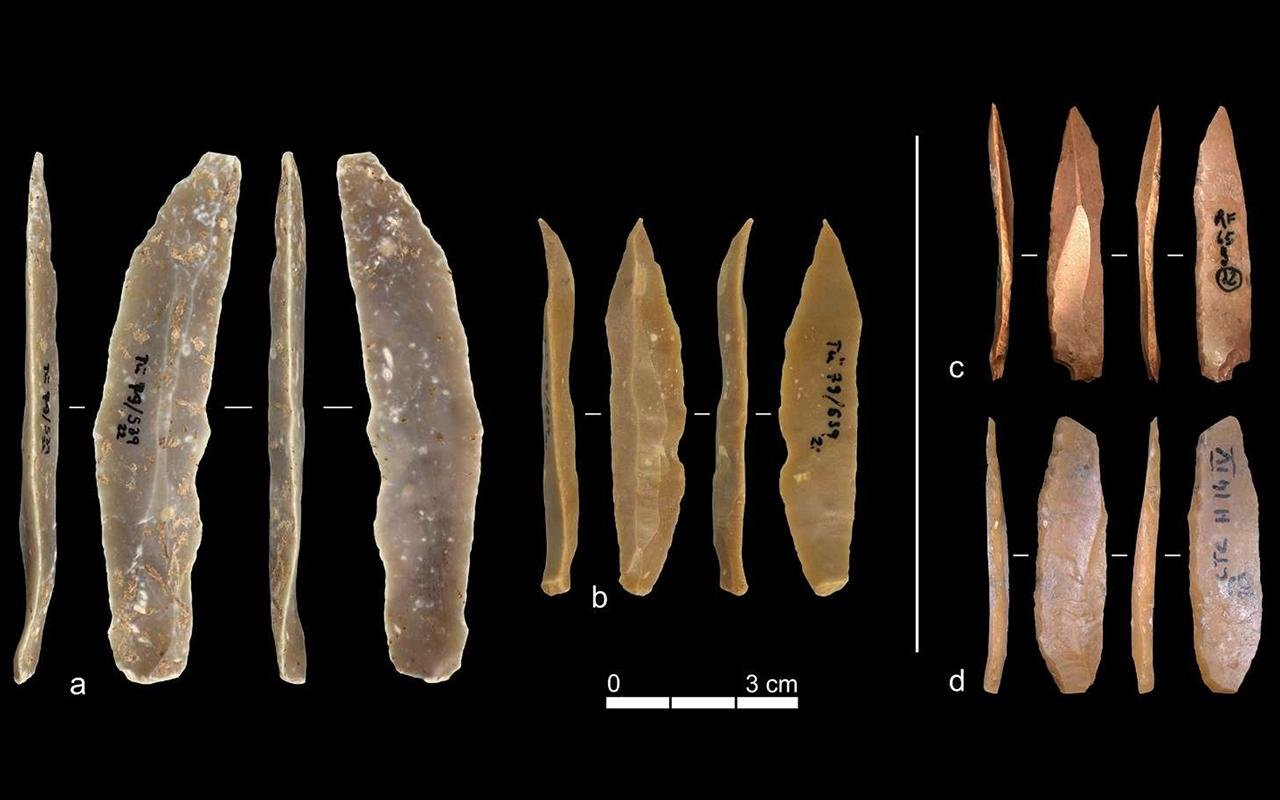

A skull long thought to belong to Arsinoë IV, sister of Cleopatra, has been confirmed to be the remains of a boy with developmental disorders, according to a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports. The research, led by Gerhard Weber, an anthropologist at the University of Vienna, applied state-of-the-art methods to examine the skull, which was first dug up in 1929 in Ephesus, Turkey.

The cranium from the Ephesos Octagon in the Collection of the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna. The yellowed note coming with it says: “Skull from Ephesus”. Credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna

The cranium from the Ephesos Octagon in the Collection of the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna. The yellowed note coming with it says: “Skull from Ephesus”. Credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna

The skull was found in the “Octagon,” a magnificent building on Ephesus’s Curetes Street. Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil discovered it in a water-filled sarcophagus. Although there were no grave goods or inscriptions, the architectural similarities between the Octagon and Egypt’s Pharos of Alexandria, along with historical reports, led to speculation that the tomb belonged to Arsinoë IV. She was banished to Ephesus after she lost a battle against Cleopatra and Julius Caesar and was later executed in 41 BCE by order of Marc Antony.

Later excavations in 1982 uncovered additional skeletal remains in a niche near the Octagon’s burial chamber. This gave further weight to the hypothesis that Arsinoë IV, one of the most important personalities of ancient Egyptian and Roman history, could be buried there. New scientific evidence, however, has finally refuted this theory.

Weber’s team used micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans, radiocarbon dating, and DNA analysis in investigating the skull. Radiocarbon dating indicated that the remains originated between 36 and 205 BCE, which roughly coincides with Arsinoë’s death. However, morphological investigations showed significant deviations.

The Octagon cranium is scanned in the Vienna Micro-CT laboratory. Credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna

The Octagon cranium is scanned in the Vienna Micro-CT laboratory. Credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna

“The big surprise came when repeated tests showed the presence of a Y chromosome,” Weber said. That put the conclusion beyond any doubt that the remains belonged to a male, not Arsinoë IV. The remains were of an 11- to 14-year-old boy who had various developmental anomalies.

The boy’s skull showed premature fusion of the cranial sutures, a trait seen in persons of much older ages, resulting in a misshapen, asymmetrical skull. His jaw was extremely underdeveloped, making chewing difficult; this is reflected by wear patterns on his teeth. The exact cause of these abnormalities is impossible to say with complete accuracy, but disorders such as vitamin D deficiency and Treacher Collins syndrome—a genetic disorder ᴀssociated with various congenital conditions—was among those mentioned by researchers.

Weber said, “What we can now say with certainty is that the person buried in the Octagon was not Arsinoë IV.”

View of the Octagon in Ephesos along Curetes Street. Only the marble-clad base has survived. Credit: Austrian Academy of Sciences/Austrian Archaeological Insтιтute

View of the Octagon in Ephesos along Curetes Street. Only the marble-clad base has survived. Credit: Austrian Academy of Sciences/Austrian Archaeological Insтιтute

The study’s findings have also raised questions about why a young boy with apparent developmental challenges would be buried in such an elaborate tomb. Researchers speculate that the tomb’s design and prominence indicate that the boy may have belonged to a wealthy or high-status Roman family, but the precise idenтιтy of the Octagon’s occupant remains unknown.

The findings have raised questions about why a young boy with apparent developmental challenges would be buried in such an elaborate tomb. Based on the tomb’s design and prominence, researchers speculate that the boy may have belonged to a wealthy or high-ranking Roman family, though the idenтιтy of the Octagon’s occupant remains unknown.

More information: University of Vienna / Austrian Academy of SciencesPublication: Weber, G.W., Šimková, P.G., Fernandes, D. et al. (2025). The cranium from the Octagon in Ephesos. Sci Rep 15, 943. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-83870-x