About 19,000 years ago, a prehistoric woman was buried inside El Mirón Cave, a huge rock shelter in Northern Spain. Her remains, discovered in 2010 by archaeologists Lawrence Straus of the University of New Mexico and David Cuenca Solana, were covered in red ochre, an iron-rich pigment for which she was nicknamed the Red Lady of El Mirón. This spectacular finding has provided a wealth of new information about Ice Age humans, and new advances in DNA analysis continue to yield fresh ideas about the populations that lived in the region before and after her time.

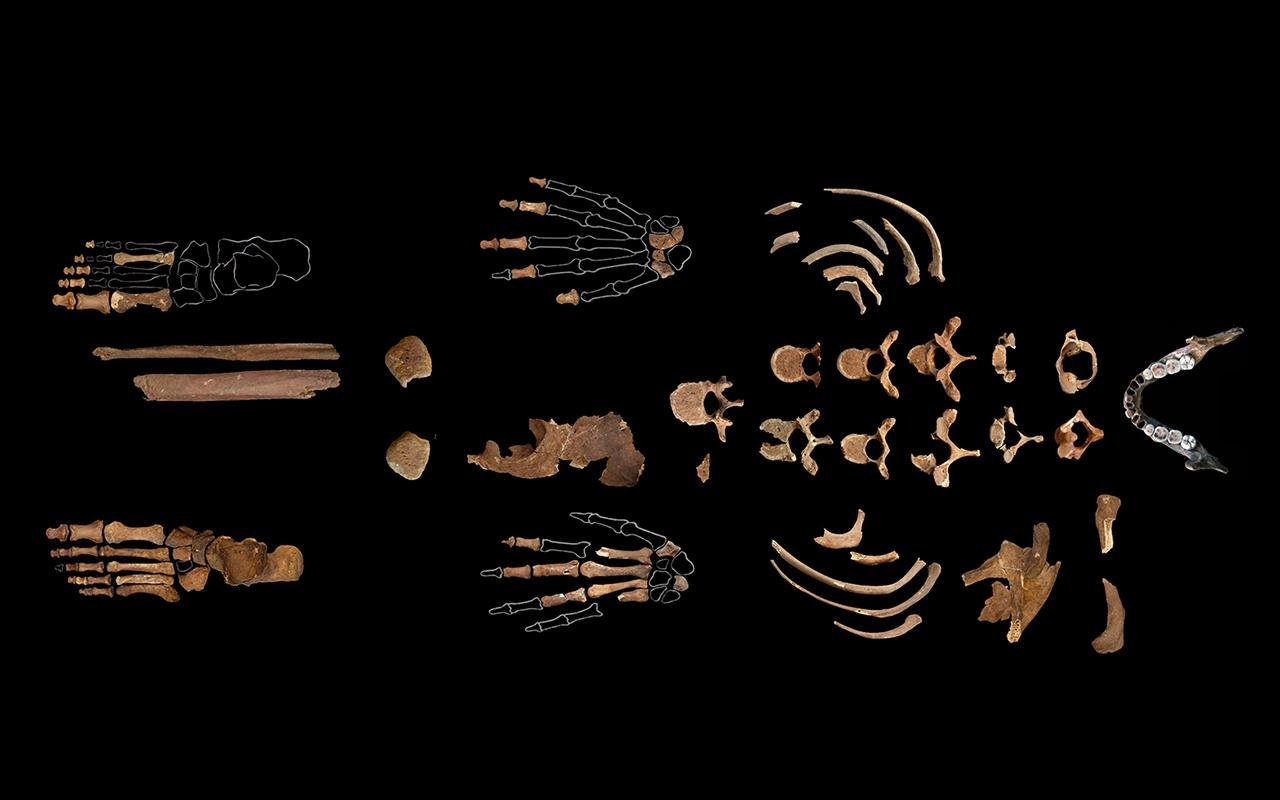

The remains of the Red Lady of El Mirón. Credit: University of New Mexico

The remains of the Red Lady of El Mirón. Credit: University of New Mexico

Genetic studies of ancient humans rely on extracting DNA from bones or teeth. But an outstanding paper published in Nature Communications shows that DNA preserved in soil—known as sedimentary ancient DNA, or “sedaDNA”—can yield crucial insights. The study, which involved Pere Gelabert and Victoria Oberreiter in Professor Ron Pinhasi’s lab at the University of Vienna, was conducted in collaboration with Straus and Manuel González Morales from the University of Cantabria. They have co-directed the El Mirón excavations for over 25 years.

According to sedaDNA analyses, humans and animals inhabited the cave at different times, corresponding to various deep archaeological layers. The study identified genetic traces of species that had not been previously recorded in the faunal remains from excavations, such as hyenas, leopards, and Asiatic dholes, wild dogs that are now found only in parts of Asia. This method is particularly exciting as it offers the possibility of uncovering past ecosystems without the need for well-preserved skeletal remains.

A reimagination of the Red Lady. Credit: University of New Mexico

A reimagination of the Red Lady. Credit: University of New Mexico

One of the most noteworthy findings of the study is the discovery of human genetic ancestry in the sediments. The analysis revealed that the artisans who made Solutrean artifacts in El Mirón Cave during the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 25,000–21,000 years ago) belonged to the “Fournol” genetic lineage. This lineage had previously been identified in remains found in France and Spain, indicating that these Ice Age hunter-gatherers moved south when climatic conditions were extreme. Later, they blended into the genetic heritage of the Red Lady, along with “Villabruna” ancestry, which had migrated into the region from the Balkans via northern Italy during the Magdalenian.

The entrance to the El Mirón cave. Credit: University of New Mexico

The entrance to the El Mirón cave. Credit: University of New Mexico

El Mirón Cave has long been recognized as a key locale for the study of human activity during the Upper Paleolithic. The new sedaDNA findings reinforce its importance by providing an unbroken genetic record spanning more than 46,000 years, covering the transition from Neanderthal populations in the Mousterian period to modern humans in the Magdalenian.

In addition to human DNA, this research recovered mitochondrial genomes from other Ice Age animals, including woolly mammoths, rhinoceroses, and reindeer. The work contributes to the reconstruction of the prehistoric European environment and provides a clearer picture of how both wildlife and humans responded to past climate change.

With the success of sedaDNA analysis at El Mirón, researchers are now looking toward the next frontier—extracting nuclear DNA from sediments.

More information: University of New Mexico

Gelabert, P., Oberreiter, V., Straus, L.G. et al. (2025). A sedimentary ancient DNA perspective on human and carnivore persistence through the Late Pleistocene in El Mirón Cave, Spain. Nat Commun 16, 107. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-55740-7